Poker & Pop Culture: Everything New Is Old Again

If you spend any time at all perusing early poker strategy books, it's hard not to come away with an uncanny feeling that what you're reading sounds very familiar.

Especially if you're a poker player yourself who studied the game seriously, you might well come away from many of these earlier texts thinking the same thought — these guys had a lot of it all sorted out long ago.

That said, there are some elements of these books that mark them as coming from another time.

The generally raised level of discourse alone sets them apart somewhat, as do some of the phrasing and syntax which though highly readable clearly are of an earlier era. The fact that titles appearing among this earliest wave of strategy texts from the 1880s through 1910s concentrate primarily on five-card draw, the popularity of which died out decades ago, also reminds us we aren't reading contemporary poker strategy.

Occasional references to cheating in these older books — more specifically, warnings to readers what to watch out for so as to avoid being cheated themselves — also remind us of saloons and steamboats and other, earlier poker settings. Even with these references, though, the emphasis in these books is primarily on poker played fairly and within the rules they describe. The authors consistently promote the skill element of poker either implicitly or directly, in some cases explicitly arguing in favor of poker being a better test of skill than other popular card games of the era.

Such books thereby function to defend poker against detractors objecting to it on moral grounds, promoting the game as appropriately "gentlemanly" (to use the era's terminology) and possessing an intellectual appeal that should make it socially acceptable to all classes.

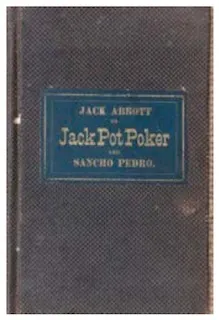

Jack Abbott, A Treatise on Jack Pot Poker (1881)

A Treatise on Jack Pot Poker by "Uncle" Jack Abbott, first published in 1881, is a good, early example of a poker title from long ago seeming to prefigure a lot of later discussion about the game.

The slim volume begins with a short history of cards and card games, then goes through the rules of "jack-pot poker." A lot of general guidance to poker players follows, including warnings to amateurs to avoid "unlimited" or no-limit games and the recommendation never to play poker on credit ("when your money gives out, quit the game").

The author also advises new players especially to keep quiet at the tables and avoid loose talk if at all possible. "A silent player is so far a mystery, and a mystery is always feared," he explains. "If you do not talk, the tones of your voice will not betray you." Sounds a lot like a present-day coach counseling new players to minimize their own tells and play "mum poker" (to borrow Tommy Angelo's phrase).

A humorous rewrite of Hamlet's famously soliloquy ("To draw or not to draw, that is the question...") and a concluding discussion of the obscure seven-up variant "Sancho Pedro" might remind us "Uncle" Jack writes from an earlier time. But much of what he has to say nonetheless speaks across the game-playing generations.

Garrett Brown, How to Win at Poker (1899)

In an even lighter vein, Garrett Brown's 1899 volume How to Win at Poker further demonstrates the game's spread by offering a teasing, non-serious sequence of lectures much more entertaining than edifying.

One notable chapter is titled "Lucky Players and How to Beat Them." As you might imagine, the advice is utterly silly, though there is something delightful in the clearly tongue-in-cheek absurdity Brown's recommendation to try to "hoodoo" such players in order to throw them off their hot streaks.

Other tactics proposed include trying to "queer" the lucky player, which here means simply cheating them in various ways, and to snatch away the player's "mascotte" or lucky charm.

There's more funny business here, including a sober discussion of the etymology of the word "poker" likening it to the fireplace implement. Since "'poker' means an iron or steel bar used for stirring a fire," we're told that provides "a foundation for the red-hot scenes that sometimes occur over the game." That leads to further associations between the game and fiery heat, concluding with speculation about how "a game in hades" dealt by the devil himself might proceed.

Everything — discussions of probabilities, dealing, terminology, rules, etiquette — is presented with an eye toward farcical joke-making, which shows the title of the book is intended satirically. The last chapter confirms the hint, proposing that poker be taught in colleges and the book be used as a required text. Those who recall Max Shapiro's comical columns for Card Player have an idea of the spirit being evoked here.

While humor tends to date much more quickly than other modes of expression, poker players today can still "get" Brown's brand of card-based comedy, having perhaps made similar jokes themselves about some of the follies produced by the game.

David A. Curtis, The Science of Draw Poker (1901)

Moving over into more sober and straightforward entries in the early poker catalogue, the title of David A. Curtis's 1901 entry The Science of Draw Poker immediately suggests a more serious approach to guide those seeking a winning strategy.

We've spoken of Curtis before here, namely his two collections of poker tales Queer Luck (1899) and Stand Pat, Or Poker Stories from the Mississippi (1906). Here Curtis turns from the literary to the mathematical, starting with a description of draw poker, running through hand rankings, rules, and odds and probabilties or the "Calculation of Chances."

A chapter titled "Studies of Actual Play" then presents commonly-faced situations and related strategic advice, most of which involves playing a tight style and according to mathematical certainty, only diverging from such precepts if game conditions suggest it advantageous to do so.

"The only safe course," says Curtis, "is first to master the general rules and afterward try to become familiar with the conditions that justify a departure from them." In other words, know what's correct, but always be ready to adapt — the kind of thing writers from David Sklansky to Daniel Negreanu would later also espouse.

Like Abbott, Curtis suggests "the timid or inexperienced player will do well to confine himself to the limit game, at least until he has mastered the principles of poker." More chapters about "Personality in Poker," "Caution and Courage," and the "Mental Discipline of the Game" prefigure Alan Schoonmaker, Jared Tendler, Tricia Cardner, and others who've offered tips for mastering the "mental game."

On that latter topic, the issues Curtis addresses show players more than a century ago dealing with the same problems plaguing many today, such as the urge of the losing player "to keep on playing after he has lost too heavily," the problems caused by playing above one's means, and the dangers of practicing poor game selection.

"It is certainly true that much can be learned by playing against experts," notes Curtis, "but it is an expensive course of tuition, and the same results can probably be attained by playing with those who have only the same degree of skill, approximately, with yourself."

R.F. Foster, Practical Poker (1904)

We mentioned last week Robert Frederick Foster — a.k.a. "R.F." — the Scottish-born writer of more than 50 books, many having to do with card games. After moving to the United States as a young man, Foster would become the card editor for the New York Sun and over the next several decades emerge as a much-valued authority on various card games.

By the start of the 1900s, Foster had already well established himself as an authority on bridge and whist, and his understanding of poker had likewise been called upon frequently, making him something like an early 20th-century Matt Savage fielding constant questions from the growing pool of poker players.

In the introduction to his 1904 book Practical Poker, Foster speaks of "having been called upon, during the past ten years, to deal with an average of eighty letters a week relating to Poker disputes alone," a trial he believes has given him "exceptional facilities for sifting out and analysing Poker Laws."

Besides offering well formulated explanations of rules and guidelines for play, Foster gives a larger view of poker's historical development. "The two great steps in the history and progress of Poker," writes Foster, "have undoubtedly been the introduction of the draw to improve the hand, and the invention of the jack-pot as a cure for cautiousness."

Algernon Crofton, Poker. Its Laws and Principles (1915)

Finally, we'll conclude with a brief mention of Algernon Crofton's 1915 entry, Poker. Its Laws and Principles, a book that takes the interesting approach of targeting losing players to provide them "maxims" and other help to break out of bad habits and turn themselves into winners.

Among the tips not to pay to draw four cards or avoiding entering a jack-pot hand with less than a pair of queens, Crofton interestingly highlights poker's skill element, making the case for the game a hundred years ago as forcefully as those making the same argument today.

"In one sense of the word, there is no such thing in the world as a skillful poker player, but there are plenty of bad ones," explains Crofton. But the good players are skillful, he insists — their skill lies in knowing the "mathematical odds of chance" better than others and letting those who are less knowledgeable "offer them bets at ridiculous odds."

"Strange as it may seem," he writes, "poker is less a game of chance than bridge or whist," a point proven by his own observation that "a good poker player playing with inferior players seldom loses," whereas such is not so much a certainty in those other card games.

Taken together, all of these early books could be said to make a similar argument in favor of poker being a game that rewards careful study, thereby elevating it to a place worthy of being celebrated (and not censured) by the culture at large.

Of course, if you're a poker player, well... you've already heard that one.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.