Poker & Pop Culture: The Congressman Who Accidentally Wrote a Poker Book

Poker players are well accustomed to legislators' unending debates over our favorite game. Indeed, laws to forbid, restrict, and/or permit the playing of poker have been part of its history ever since the game's introduction back in the early 19th century.

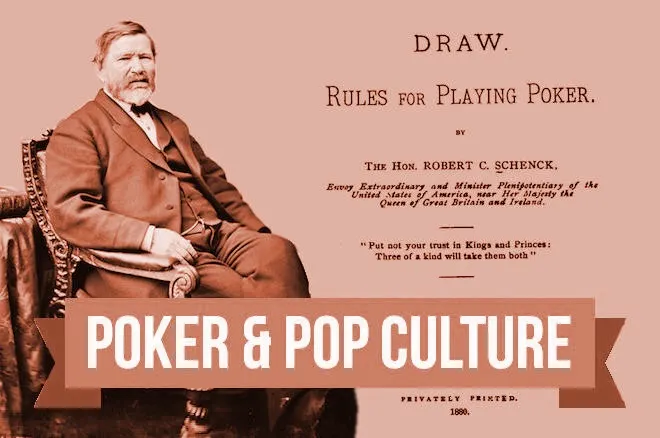

It is perhaps surprising to learn, then, that the person often credited with writing one of the earliest rulebooks of poker was in fact a former U.S. Congressman. It was by accident, really, that Robert C. Schenck, once a member of the House of Representatives, came to author a short book explaining how to play five-card draw.

After representing his native Ohio in Congress from 1843-1851, Schenck served as an ambassador in South America, supported Lincoln in the 1860 election, fought with the Union as a general in the Civil War, and served once again in Congress as one of Ohio's representatives from 1863-1870.

Upon losing a close race for reelection in 1870, Schenck was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant as Minister to the United Kingdom and the following summer he sailed to England where he would remain for the next five years.

It was while he was in London that Schenck would pen his brief primer, Draw. Rules for Playing Poker. Some have suggested he wrote the book in order to introduce the American game to Queen Victoria, although in truth it was following a weekend of card-playing with friends in Somerset that Schenck had been asked to write down the rules by his host. Complying with the request, Schenck was later surprised to see his rules having been reprinted and circulated by his friends as a book.

Schenck's little "how-to" book appeared some time after editions of the American version of Hoyle's Games first began including references to poker, with the first mention coming in the 1845 edition of the "American Hoyle." Schenck's slim volume nonetheless stands as what many regard the earliest example of a book entirely devoted to poker.

It is tempting to think that an ex-Congressman and U.S. ambassador having authored such a book must indicate that poker — which as we've been covering was still a game played in saloons, gaming dens, and on steamboats and rife with cheaters, cardsharps, and various ne'er-do-wells — had become relatively accepted in American popular culture.

That wasn't quite the case.

Schenck himself explains in "The Author's Apology" — added when the book was later reprinted in the U.S. in 1880 — that even though the printing of his book had been "intended as a compliment" by his English friends, its appearance had "unwittingly brought down on me the wrath and reprehension of so many good people in America."

At that point in his life, Schenck had already endured his fair share of public controversy. That's because by the time Schenck wrote that "Apology," his reputation had suffered considerably thanks in particular to his involvement in a speculative venture gone wrong — the Emma Mine Company of Utah.

It hadn't been long after Schenck got to London in 1871 that he was recruited by Emma Mine to try to sell shares of the company over in England. Unsurprisingly, the Minister drew criticism for having done so, although when Schenck asked Grant for guidance the president told him he could continue as long as he conducted himself honestly.

In early 1876, the Emma Mine Company collapsed, which meant ruin for those English investors to whom Schenck had sold shares. The House's Foreign Relations Committee met to discuss the situation, and it was decided Schenck would have to relinquish his post as Minister. Soon he was back in Washington, D.C. practicing law.

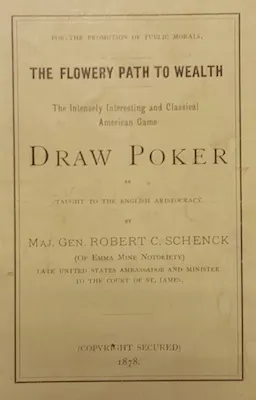

All of which means when Draw. Rules for Playing Poker was republished in America by a private Brooklyn printer a few years after his return, Schenck had already drawn "the wrath and reprehension" for reasons having nothing to do with his endorsement of draw poker. In fact, some of the earlier reprintings of the original pamphlet made parenthetical reference on the title page to the author being "Of Emma Mine Notoriety." (That to the right is the title page of one from 1878, the image sent to me by an academic researcher friend of mine who recently secured a copy of the pamphlet.)

Despite being a Congressman, Civil War general, and an ambassador, when Schenck died in the spring of 1890 it was that tiny book about poker that appeared destined to be his most lasting legacy. A note by the editors of LIFE magazine just a few weeks after his passing shows how the name Schenck would forever be associated with America's card game.

"Many a man makes his fame out of the most unexpected materials," they wrote. "Who ever thought of General Schenck without thinking at once of poker? And yet General Schenck's poker was only an incident in a pretty active life."

Even so, Schenck's "apology" shows how when it came to the culture at large, many Americans still weren't too sure about the game.

As for the book itself, Schenck does a good job outlining the rules for five-card draw while including some strategy advice as well. The rules are essentially what we know of the game, describing the deal, an opening round of betting, the draw, a second round of betting, and (if necessary) the showdown. Meanwhile, the strategy tips also conform pretty well to what we know of the game today.

Schenck actually begins the book by stating "The deal is of no special value and anybody can begin." However, here he seems to be referring more to the logistics of getting started rather than the significance of position. Indeed, later on his advice demonstrates an understanding that position matters.

The Congressman explains the role bluffing can play in the game, too.

"It is a great object to mystify your adversaries," writes Schenck. "To this end it is permitted to chaff or talk nonsense, with a view of misleading your adversaries as to the value of your hand, but this must be without unreasonably delaying the game." Though written almost a century-and-a-half ago, Schenck's comments are still pretty timely, wouldn't you say?

Schenck talks about tells as well, noting how "a skillful player will watch and observe what each player draws, the expression of his face, the circumstances and manner of betting, and judge, or try to judge, of the value of each hand opposed to him accordingly."

Toward the end come some specific suggestions about how to play certain hands, and while these pointers hardly reach Mike Caro-levels of detail they do articulate commonly agreed-upon ideas about frequently-faced situations in five-card draw.

Schenck's concluding summary of advice to the draw-poker player indicates the former Congressman possessed not only a solid understanding of the game but a certain level-headedness that probably helped him at the tables as well: "The main elements of success in the game are: (1) good luck; (2) good cards; (3) plenty of cheek; and (4) good temper."

In his historical survey of games' impact upon American culture Sportsmen and Gamesmen, John Dizikes tells how "Schenck had come back to America in 1876 in what would have conventionally been thought of as a state of disgrace. But he seems not to have felt this or to have been the least bothered by his dismissal, keeping throughout the good temper that he had identified as one of the poker player's most necessary attributes."

Schenck would be officially cleared of any wrongdoing with regard to his representation of the failed Emma Mine Company. Dizikes suggests he lived out his remaining days continuing to play poker in the nation's capital where a number of elected officials were known to enjoy the game as well.

As many still do. When not battling over legislating the game, that is.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.