Poker & Pop Culture: Professor Henry T. Winterblossom Does the Math

Appearing not long after Robert C. Schenck's modest pamphlet-turned-book explaining the rules of draw poker came another slim volume, one that can rightly be regarded as the earliest formal poker strategy title. Published in 1875, The Game of Draw-Poker, Mathematically Illustrated by Henry T. Winterblossom not only provided 19th-century poker players a thorough explanation of the game's odds and probabilities, but affords us a glimpse of the cultural standing of poker at the time it was written.

The mere publication of a book of poker strategy announces the game had already begun to be distinguished from other gambling games as one that rewarded close study and was not wholly subject to the whims of chance. That said, the author of The Game of Draw-Poker is especially cautious to avoid suggesting poker is not gambling, and thus recommends the game should be looked upon warily as a potential danger both to the individual and to society as a whole.

Poker: A Growing National Threat

First, a quick word about Winterblossom, described on the title page as a "Professor of Mathematics."

Around the time of the publication of The Game of Draw-Poker there appeared a short article in The New York Times titled "The National Game" that described poker's growing popularity with some trepidation. After noting that baseball had been the generally agreed-upon "national game," the article's author worriedly wonders if perhaps another game is about to wrestle away the title.

"We should be sorry," writes the author, "to see such an active and heathful sport exchanged for a game of cards. But if we are to judge anything from a new variety of literature that is spreading through the newspapers, we are forced to the conclusion that the national game is not base-ball, but poker."

Fears about poker's spread are next articulated, with the NYT expressing a wish the game would remain confined to "the rough South-west and to those far-off regions where the Outcasts of Poker Flat are real personages" — a reference to the popular 1869 short story by Bret Harte we've already discussed.

The author discusses some poker-related strategy articles that had begun to appear in newspapers of the day, then also includes the publication of The Game of Draw-Poker as reason for further concern, noting incidentally that the "author, by the way, is understood to veil himself modestly under a pseudonym; and he is said to be a member of the Lotos Club."

The Lotos Club was a literary club founded in 1870 in New York City whose membership included many of the era's most famous artists, writers, journalists, and critics. Named after the famous Alfred, Lord Tennyson poem "The Lotos-Eaters," one of its earliest members, Mark Twain, gave the club an informal, poker-related second game — the "Ace of Clubs." (Twain, you'll recall, himself wrote a memorable poker story involving a fictional professor — "The Professor's Yarn.")

Even so, the club's constitution specifically prohibited "the games of poker, loo, and others known as round games" from the "amusements" permitted in the club house.

The NYT writer fears the spread of poker and its recent promotion as "the national game" may be indicative of an impending moral decline in America. He finishes with reference how our friend Robert Schenck was still denying having authored his book which as we discussed last week had been originally published without consent. (Schenck would eventually own up to it in 1880.)

No wonder, then, that the author of The Game of Draw-Poker had wanted to hide behind an assumed name. Poker was thought by many to be a danger and a threat, which meant even a sober analysis of the game's mathematical truths could be construed as destructive.

Study Poker Strategy and Lessen Its Danger

The complete title of Winterblossom's book sounds as though it were designed to appeal primarily to a certain, analytically inclined segment of the poker-playing crowd: The Game of Draw-Poker, Mathematically Illustrated; Being a Complete Treatise on the Game, Giving the Prospective Value of Each Hand Before and After the Draw, and the True Method of Discarding and Drawing, With a Thorough Analysis and Insight of the Game as Played at the Present Day by Gentlemen.

Despite that long title, the book itself is short — just 72 pages filled by a preface and six chapters. In a similar vein to "The Author's Apology" that precedes Schenck's book, Winterblossom's preface puts forth disclaimers distancing the author from the idea that he might be mistaken for someone desirous to encourage his audience to gamble at cards.

After noting that the urge to take risks has been felt by the human race "from time immemorial," Winterblossom explains "it is not our purpose to harm the reader by endeavoring to prove that gambling is indigenous to the human family, and that primeval man was born with a dice-box in his hand."

Don't make the mistake, he says, of thinking that just because humans have always gambled that it isn't a vice to be avoided. Not only is poker a "selfish" game that involves deceit (or "artifice"), "Draw-Poker is strictly a gambling game, and one which, if [readers] will take the author's advice, they will shun as they would a faro-table or a horse-race."

It's okay not to play poker, Winterblossom assures his readers, reminding them "their position in society will not be imperilled in the least by the ignorance of this accomplishment" of learning the game.

In fact, Winterblossom's wish to explain the odds and probabilities of draw poker is meant to encourage readers to be able to weigh more accurately the risks involved, thereby making the game better understood and less apt to be entered into recklessly.

Think about it. In these arguments over the relative proportions of skill and luck in poker — still raging today, two centuries after the game's introduction — it's important to keep in mind the individual player's knowledge of strategy, including the math involved. After all, for those with little or no understanding of odds and probabilies, poker truly is a game mostly determined by chance, and thus, maintains Winterblossom, as dangerous as any other gambling game.

Winterblossom creates a kind of maxim out of this position, an eminently quotable one at that:

All games of chance create a morbid appetite in those who indulge in them, in proportion to their ignorance of the mathematical basis upon which those games are constructed.

In other words, not knowing the math makes poker an even more dangerous recreation than it already might be. In this way does Winterblossom position himself as promoting something positive with his book.

If you're going to play poker at all, he suggests, it's "a vital question to know what kind of hand one should stand on, and what kind [one] should throw up." He even goes so far as to maintain "that the player who will avail himself of the advantage which certain combinations give, will, in the majority of cases, have it in his favor, and must, in the long run, win."

Those are Professor Winterblossom's calculations — you must learn strategy if you want to avoid the gambling-related pitfalls of poker.

Learn the Odds, Improve Your Chances

The preface includes some other interesting proclamations about poker, including pointing out how money is an essential element of the game. "Draw-Poker, unfortunately, is one of the few games that cannot be played so as to afford any pleasure, without the interchange of money," writes Winterblossom. "Indeed one might as well go on a gunning expedition with blank-cartridge, as to play Poker for 'fun.'"

He adds as well that while bluffing is another important element of the game, the art of bluffing lies somewhat outside of the scope of his intention to deliver a succinct summary of the math underpinning the game. "To convey to the reader an adequate conception of precisely what [bluffing] is and how and when it is to be used, would necessitate the invention of a new language," confesses Winterblossom, a language much more involved and complex than the humble one he intends to employ to communicate odds and probabilities.

An early example of the "professor" explaining a meaningful poker-related concept comes when he shows your chances of completing a flush draw are not affected by how many players are in a given hand — a point helpfully explained here recently by Robert Woolley in a strategy article titled "Six Ways of Correcting a Common Probability Error."

The rest of the book unsurprisingly shows Winterblossom advancing the idea that learning your chances of hitting those draws and other probabilities associated with being dealt certain hands helps a player appreciate the relative value of hands both before and after the draw. Such knowledge is what separates the best players from the inexperienced, with the latter group too often done in by playing "poor original hands" (i.e., starting hands) and paying too greatly to chase draws.

"The fundamental error of the 'bad player' (who is the representative of bad playing generally)," Winterblossom notes, is that "he wants to be in every hand." Such a player can't fold his "bob-tail flushes, intermediate straights, and odd cards" as he should, the author notes, adding that "if one will reflect a moment on the absurdity of this course, he must see that it is almost impossible to win under the circumstances."

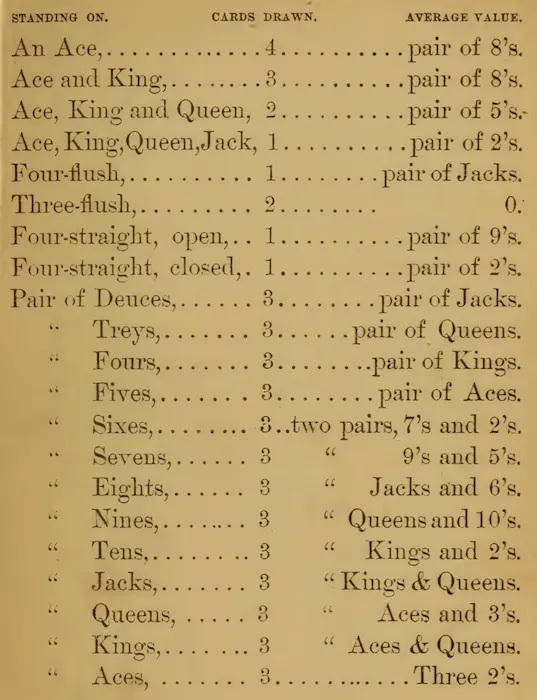

He even includes a helpful table (see above) that gives an idea what the "average value of a hand" will be following various types of draws. This is nearly a century-and-a-half ago, mind you — well before such tables became more familiar to us, especially during the post-"boom" rise of online poker this century.

Becoming a Smart, Observant, Well-Rounded Poker Player

The Game of Draw-Poker's good advice extends beyond just tables and other numbers.

Being attentive to other players' actions and behavior is key, the author explains, maintaining "the first great requisite, in playing the game of Draw-Poker is to permit nothing to escape your observation." He also suggests ways to profile your opponents according to three common player types — "the close player, the conservative player, and the reckless player."

The "close player" is too tight, only playing strong hands and never bluffing, while the "conservative player" more smartly adapts to present game conditions, changing styles only when it is advantageous to do so. Meanwhile the "reckless player" is the one playing every hand, unable to resist bluffing at every opportunity, and — in Winterblossom's withering view — "is always a loser."

He also addresses ethics and etiquette, recommending that players "always control your temper," "win and lose with equanimity," and avoid delaying paying off debts. "Do not owe anything around the table," he says — "settle at once."

Winterblossom further notes how over the last couple of decades draw poker had gotten away from the "unlimited" betting and "propensity to 'go better'" with increasingly large bets and higher stakes (a legacy of the English game of brag he notes). During the time of his writing, "the amount at stake at any one time is usually limited to a moderate sum," Winterblossom observes, commending this as a favorable development making poker less potentially "disastrous."

For him, "there is no science whatever necessary in the unlimited game," a position to which many of today's best no-limit players would likely object. "It is purely a game of intimidation," he believes.

That said, he knows there are some out there who don't want to place limits on their betting. For them, Winterblossom has a recommendation as well.

"If the reader prefers a large or unlimited game, it is to be presumed that he requires no advice at our hands."

Winterblossom certainly understood his own limits — and that some of his readers had none.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.