How Much Luck and Skill/Edge Exists in a Game of Open-Face Chinese Poker? Part I

Open-face Chinese has become one of the most popular games in poker. Top pros like Jason Mercier, Barry Greenstein, and Shaun Deeb have become unofficial ambassadors for the game, while dozens of other pros can be found playing the game either late into the night or on their tablets. One of those players is Nikolai Yakovenko, who helped create the ABC Open-Face Chinese Poker iPhone app.

Yakovenko, also known as "Googles," is originally from Moscow, Russia and is now a poker player and software developer that resides in Brooklyn, New York. After several years at Google New York working on ranking algorithms, he's been developing independent software projects ever since while making both World Series of Poker and World Poker Tour final tables. Here Yakovenko, who has $313,598 in WSOP earnings, examines how much luck (variance) and skill (edge) there is in a game of OFC.

I have a confession to make: I don’t always play Open Face Chinese Poker (OFC) correctly. I’d like to think that it’s because I’m playing for pride, or for low stakes, but then when I’m playing for bigger stakes during the World Series of Poker at the Rio, I find myself making those same plays. “I’ll gamble because it looks close and I’m winning. Gotta give these guys some action.”

It’s not like the right plays with all of the odds were staring me in the face, and I chose to play differently. If I knew for sure the 100% correct play, I would have made it every time, but sometimes, you don’t know for sure, or you know that it’s gotta be close. You don’t want to count all the cards or evaluate all of your opponent’s current ranges. You just want to play. You have an idea of how you’re doing against your opponent, and just want to move quickly to get more hands in, get value for the rake, and make sure that your yawning opponents don’t get bored, frustrated or quit. Why calculate all of the outs, if you can just play the hand your way, knowing that most of those plays are pretty good plays, or at least close enough.

In regular poker, we call this strategy, or to some extent style. Very few of us play hold’em tournaments like Michael Mizrachi, Phil Hellmuth and John Juanda. We analyze individual decisions, sometimes ad-nausea, but we also accept that individual players play their own certain way, and that they can be successful with very different approaches.

But with a game like OFC, which seems so solvable, there’s an instinct to dismiss strategy and style, instead asking “what is the correct play here” at every point in the hand.

It is true that you could plug your OFC game into a super-computer and get the correct, un-exploitable move, a move that would be correct against any set of opponents. However, it would take about 1,000 years to get the computer’s foolproof answer — you’ll be in Fantasyland with Biggie & Tupac by the time it’s over.

As a player with a chess (and more recently a backgammon) background, I’m perhaps more used to fighting this need to get the right answer and move on, disregarding elements of strategy. It’s hard to improve your game, if you focus on making the best move every time, rather than considering what your plan is for the hand, or how to best exploit your opponents’ long-term tendencies.

In chess, the grandmasters (the best 1000 or so players in the world) will make the mathematically correct play, or at least a move that doesn’t give up significant edge, in 95% of all cases. Even the lower-titled internationally rated chess masters (such as poker players Greg and Jen Shahade) will make the perfect move, or a move that’s indistinguishable from the perfect move, something like 90% of the time. You can never get a five-move maneuver past them without being noticed.

And yet, the various chess masters and grandmasters play vastly different styles and end up in very different kinds of positions. There are forks in the road, often early in the game, where two or more moves have something like the same average expectation, but a vastly different range of possible outcomes. A player who likes complicated positions will steer the game toward complicated positions. A player who likes open space will try to clear ranks and files. His or her opponent would be smart to do the opposite.

This is even clearer in backgammon. There are famous debates on opening rolls such as 2/1 and 4/3. Several ways of playing those rolls have the same exact average value (within 0.1% of a point), but vastly different distributions of outcomes. Some plays will double the chance of the game resulting in a gammon for one of the players, without changing the average value of the position. Other plays make a gammon very unlikely. These aggressive moves are often preferred by the professionals, the gamblers, and by the stuck.

Getting back to poker, everyone from Mizrachi to Juanda to Joe the Grinder will probably make 80% of his or her tournament hold'em decisions the same way. The reason that a player folding quads or checking behind with top-full on TV gets so much attention is because these plays happens so rarely. Most hands are clear folds, some of the rest are clear raises, and the rest ... well there are decisions, but some of those decisions are clearly wrong.

The differences in style, as well as in skill and in long-term success, are made in those 20% of decisions that are not clear and obvious. In OFC, as in chess and backgammon, and as in hold’em, a move might be the “right play,” but if you don’t know how to play the follow-up move, it might be wrong play for you. And in OFC, like in hold’em, against some players, the “right play” is not the best play that you can make.

How Much Skill? How Much Luck?

OFC players seem to hold the simultaneous views that the game has a high degree of luck, and also that there are tremendous differences in player skill.

They aren’t wrong. It’s hard to watch experienced OFC players like Shaun Deeb or Melissa Burr (aka Burrrrrberry) playing quickly & confidently, or better yet, watching them flip over a card, scan the table with their eyes several times — wheels turning — then confidently making a move that you don’t understand, and not conclude that there are tremendous difference in skill amongst the competitors.

At the same time, anyone who watches a few OFC hands can see that an amateur player is just as likely to make quads* or a straight flush as the pros, and that the luck of the draw greatly outweighs skill in OFC, over hours at the casino, and over days of play on the apps.

*Actually, amateurs who play a kicker with their bottom trips immediately are much less likely go make quads. That’s why some pros leave the fourth bottom spot open when their quads are live.

In a rather crude way, I tried to answers these questions: how much luck (variance) and skill (edge) is there to an OFC game, heads up with Fantasyland.

It’s hard to play hundreds of rounds of OFC against real people, but the new version of the OFC Open Face Chinese Poker iPhone app provided me with a good proxy. We wrote a sophisticated computer AI, which plays at a skill level comparable to a pretty good intermediate player. In my Frankenstein’s imitation of its creator, the AI plays very aggressively, holding out for big bonuses and playing big pairs up top for Fantasyland whenever it’s reasonably feasible to make the hand without fouling. The AI doesn’t always make those big hands, so it fouls a lot. But it does a good job of maximizing big hands that it gets dealt, and it tries to avoid fouling its hand, especially late in the round.

I would hope that I’m a long-term favorite against this AI, with room to spare, but how much am I a favorite and what kinds of swings should I expect to take in the process?

After a couple hundred hands, I have the answer. Or rather, I have two answers. I played long matches against the computer with two different styles.

Frankenstein Versus the Mad Russian

Over 223 heads-up OFC hands, I punished the ABC 2.0 computer with a very aggressive style. From the start of each hand, I would try to go for Fantasyland. Every time I had an Ax to start, I’d play it in the middle, and every Qx went on top. I would not pair the Qx if I had really poor odds of qualifying the hand, but I would pair the Ax in the middle almost automatically, racing to qualify with some kind of two pair on the bottom, and hoping to catch a couple of running cards for a big pair on top.

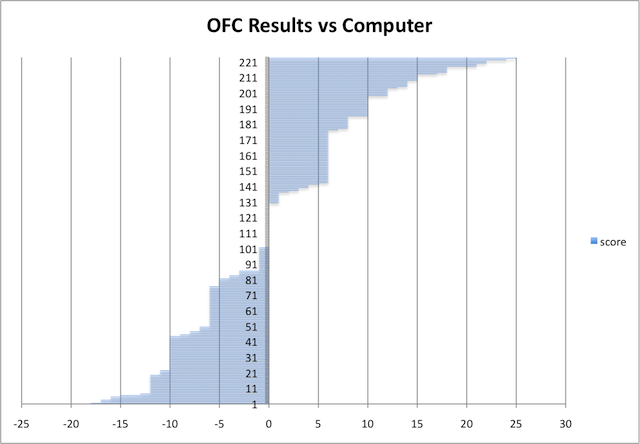

I did not purposefully make bad plays, and indeed, I played my best, given that I had a mission to go for big hands from the start whenever possible. After 223 hands, I was up +78 points, for an average win of +0.35 points/hand. The individual hand scores ranged from +25 for me to -18 for the computer, with a standard deviation of 9.0 points per hand. The standard deviation simply means that 2/3 of all hands fell in the range of +9 to -9, or that you should expect to win or lose around +-9 points per hand, depending on the luck of the draw.

Based on this data, I’m a long-term favorite against my computer opponent, but for each hand, the variance (the luck factor) is 20 times larger than the skill advantage. And this was for heads up OFC, which is generally less volatile than the 3-handed or 4-handed game.

The +0.34 points/hand edge seems small, although it’s far from trivial. I wouldn’t read too much into the specific number, as 223 hands isn’t really enough to establish a player’s advantage precisely. Consider a single hand that has QxQx up top and is ready for Fantasyland. If that hand fouls instead for -6 points, that’s equivalent to a 20-point swing right there.

What you can tell from 223 hands, however, are player tendencies. The computer fouled 37% of its hands, and went to Fantasyland on 2.7% of the hands that it was dealt. I went to Fantasyland 17 times (7.6% of the time), and fouled 40% of my hands in the pursuit.

I made +219 points on my Fantasyland hands against the computer’s 45 points, so while I fouled too many hands to get there, I beat the computer because I was more successful at getting to Fantasyland. My average win on Fantasyland hands was +12.9 points per hand, which is consistent with what is the accepted value of the Fantasyland bonus.

The computer and I won about the same number of hands, but my high-end wins were bigger and more frequent. We both played aggressively for big bonuses, but over 200+ hands, I was better at getting those bonuses without fouling.

*This is the first of a two-part series dedicated to luck (variance) versus skill (edge) in OFC. Check back later this week for Part II.

Get all the latest PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!