Poker & Pop Culture: Risk and Reward in Board Rooms and Card Rooms

"Every possible transaction in life is a risk, and involves the question of loss and gain."

So writes John Blackbridge on the first page of his 1875 guidebook The Complete Poker-Player. It's one of the earliest book-length works about the game, and it begins with a defense of gambling in general and poker in particular.

While "Blackbridge" is thought to be a pseudonym, the author does identify himself on the title page as an "actuary and counsellor at law." Perhaps it isn't surprising, then, to see him discuss right away some of the connections between gambling on cards and other forms of risk, including some from the world of business and finance.

Blackbridge notes how how the term "gambling" has negative connotations, evoking "the idea of greater or less immorality, in connection with certain acts of producing pecuniary loss or gain." He observes how because the term had become so "opprobrious," it was no longer being applied to "respected" occupations such as the ones pursued by investors in stocks, by bankers and businessmen, and (as an actuary well knows) by those who buy and sell insurance.

That's wrong, argues Blackbridge.

"All such schemes are as essentially and absolutely 'gambling' as the casting of dice for drinks at a bar, but most of them are of undoubted benefit to Society, they are respected by the community, and protected by law," he writes.

There are numerous connections between the world of business and finance and the game of poker. The many examples of stock traders, fund managers, and professional investors who have found poker providing them uncannily similar challenges helps prove the point.

Erik Seidel, Cliff Josephy, Dan Shak, Andy Frankenberger, Jason Strasser, Bill Chen, Rep Porter, Matt Glantz, James Vogl, and Steven Begleiter are just a few of many who have found success at the poker tables while also having had considerable experience trading stocks, managing funds, and exploring other types of finance-related "gambling."

Looking at it from the other direction, there are also many others more noted for their successes in the world of business who have found poker a favorite, serious recreation. Such individuals have often and in different ways echoed Blackbridge's argument when citing parallels between poker and other "respected" forms of risk-taking.

A Game of "Information Processing"

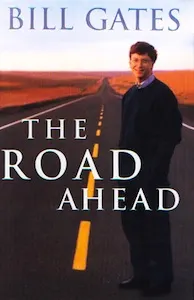

Last week Forbes listed Microsoft founder Bill Gates's net worth at $84.9 billion, putting him atop all of their lists as the richest person in the world.

The story of Gates and his friend Paul Allen starting the company long ago has been told many times, including by Gates himself in his book The Road Ahead, first published in 1995 and revised a year later. Not everyone necessarily knows that Gates, too, is a poker player, something he writes about in his book.

Gates opens his narrative describing his first experience with programming and how at age 13 he wrote his first software program — a game of tic-tac-toe. It was the late 1960s, and the early computer didn't even have a screen, just an attached printer which after a long delay would print out moves in response.

He tells how he and Allen started their own company in 1975 — calling it "Micro-soft" (before soon dropping the hyphen) and funding it themselves. "Some of the money I had came from late-night poker games in the dorm," explains Gates. "Fortunately, our company didn't require massive funding."

Later in the book Gates fills in more details regarding those Harvard poker games. He tells how like many college students, he skipped class a lot and crammed at the end just before exams, making it "a game — a not uncommon one — to see how high a grade I could pull while investing the least time possible."

What did Gates do when not attending class? "I filled in my leisure hours with a good deal of poker, which had its own attraction for me," he explains.

"In poker, a player collects different shards of information — who's betting boldly, what cards are showing, what's this guy's pattern of betting and bluffing — and then crunches all that information together to devise a plan for his own hand," Gates writes. "I got pretty good at this kind of information processing."

"The experience of poker strategizing — and the money — were helpful when I got into business," he says.

Poker, Gates maintains, involves the kind of risk that can be managed and even minimized by those who able to employ an effective, knowledgeable strategy. Thus does he differentiate poker from other gambling games in which the house always has a permanent edge.

"I think of poker as mostly a game of skill," he says. "Although I play blackjack sometimes when I'm in Las Vegas, the gambling games that are mostly luck don't have a strong appeal for me."

The Object of the Game: "Maximizing Your Gains"

It doesn't take long when looking around the world of business and finance to find many more examples of poker-playing entrepreneurs.

Options trader Jeff Yass, one of the founders of the Susequehanna International Group and its managing director, is yet another poker-playing investor. In Jack D. Schwager's 1989 book The New Market Wizards: Conversations with America's Top Traders, Yass sounds a lot like Gates when looking back at poker games in college.

"My friends and I took poker very seriously," says Yass. "We knew that over the long run it wasn't a game of luck but rather a game of enormous skill and complexity."

Yass likewise connects the measuring of risk and reward in poker with that encountered in the business world, noting how in "both poker and option trading... the primary object is not winning the most hands, but rather maximizing your gains."

Investor and hedge fund manager Steven Cohen, founder of S.A.C. Capital Investors with an current estimated net worth of $13 billion, likewise grew up playing poker, as he explained to The Wall Street Journal for a 2006 profile.

"He began playing poker frequently as a high school student, he recalls, and would sometimes arrive home at 6 a.m. after an all-night game, hand the car keys to his father, then head to bed without saying a word." Cohen was a winner at those games, apparently. His brother Donald reports how he'd "look at his desk in the morning and see wads of $100 bills."

Cohen continued to play in college as he began to study and learn more about the stock market, and looking back affirmed that poker "taught me how to take risks."

Variance in "The Real World"

In 2010, journalist Scott Patterson looked back on a group of Wall Street hedge fund managers known for their having successfully applied quantitative analysis investment strategies. His book's title gives the group a name while also signaling the scope of its story — The Quants: How a New Breed of Math Whizzes Conquered Wall Street and Nearly Destroyed It.

The best seller explores in detail the data-driven, math-centric investing strategy and some of its more famous practitioners, with the story starting just before the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis that exposed some of the critical flaws of an approach guided by the idea that "The Truth" (with a capital "T") "was a universal secret about the way the market worked that could only be discovered through mathematics."

The book draws comparisons between investing and card games, and in fact early on highlights the influence of Ed Thorp, the math professor, writer, hedge fund manager, and — most famously — blackjack player who in 1962 wrote the groundbreaking Beat the Dealer that outlined for a mass audience how card counting worked as a means to overcome the house advantage in blackjack.

Further reinforcing connections between poker and investing, the book's first chapter describes a celebrated event from early 2006 — the "Wall Street Poker Night Tournament" that took place in a midtown Manhattan hotel. It's a way of introducing some of the book's titular characters — Peter Muller, Cliff Asness, Ken Griffin, and Boaz Weinstein — all significant "players" on Wall Street.

They were also dedicated poker players, too, some especially so. "They were insane about poker," writes Patterson, referring to a few of them. He notes how Morgan Stanley's Muller in particular was consumed by the game, playing World Poker Tour events and elsewhere. "He played online obsessively and even toyed with the bizarre notion fo launching an online poker hedge fund," explains Patterson.

The private, $10,000 buy-in tournament was played for charity, raising nearly $2 million to support math programs in New York City public schools. Also mentioned taking part were poker pros T.J. Cloutier and Clonie Gowen, as well as one of the more famous investor-slash-poker players David Einhorn who a few months later would finish 18th in the 2006 World Series of Poker Main Event.

In the tournament, Muller and Asness make it to heads-up, with Muller ultimately coming out on top. The last hand was a preflop all-in in which Muller's king-seven outran Asness's ace-ten when a king spiked on the river.

"Odds were against it, but he won anyway," remarks Patterson, who then adds a line foreshadowing the longer study to come.

"The real world works like that sometimes."

Good Players Make Good Traders, and Vice-Versa

Risk manager and financial author Aaron Brown is given a lot of attention in The Quants, too, as well he should as the author of The Poker Face of Wall Street (2006), a book that convincingly analyzes and explains the many ways poker strategy applies in the world of trading.

"Poker has valuable lessons for winning in the markets, and markets have equally valuable lessons for winning at poker," maintains Brown, stating a thesis he then proves at length, covering both "poker basics" and "finance basics," then showing how often the risk-managing strategies of each overlap.

Along the way Brown intersperses entertaining stories of his own poker playing, including tales of playing underage in the famed Gardena card rooms during the 1970s on through his college and graduate school days.

Also worth recommending for those with an interest in the subject is Michael Lewis's Liar's Poker (1989) which thoroughly documents 1980s Wall Street from the perspective of a bond salesman in the heart of the action.

The title comes from the gambling game Lewis presents as something of an obsession among many traders of the day, the one involving the digits of the serial numbers printed on dollar bills and players taking turns bidding on how often a particular digit appears among the players' bills until one challenges another's bid.

The game, maintains one such trader, "had a lot in common with bond trading. It tested a trader's character. It honed a trader's instincts. A good player made a good trader, and vice-versa."

It's a game that can — and often does — involve bluffing, and as Lewis explains it forces players to ask "the same questions a bond trader asks himself," such as...

- "Is this a smart risk?"

- "Do I feel lucky?"

- "How cunning is my opponent?"

- "Does he have any idea what he's doing, and if not, how do I exploit his ignorance?"

- "If he bids high, is he bluffing, or does he actually hold a strong hand?"

- "Is he trying to induce me to make a foolish bid, or does he actually have four of a kind himself?"

Such questions are familiar to players of other kinds of poker, who constantly ask them as well.

Conclusion

That's only scratching the surface of the subject, really. There's also business magnate Carl Icahn's poker playing and the story of his allegedly having won $4,000 while in the Army, money he then used to make his first investment (a tale echoing the one about Richard Nixon financing his first Congressional campaign with poker winnings earned while a Naval officer in WWII).

And, of course, there's the banker and businessman Andy Beal, the poker-playing star of both Michael Craig's The Professor, The Banker, and the Suicide King (2005) and multiple high-stakes poker games played for millions against a group of pros collectively referred to as "The Corporation" — a very business-like team name, if you think about it.

Suffice it to say, the fact that poker and business have so much in common likely helps to explain the game's appeal in a capitalist country like the United States. Such parallels might also be used to defend poker against charges of "immorality."

"If social circles welcome the banker and merchant who live by taking fair risks for the sake of profit," writes John Blackbridge, "there is no apparent reason why they should not at least tolerate the man who at times employs himself in giving and taking fair risks for the sake of amusement."

Incidentally, that line from The Complete Poker-Player was one of several highlighted by the author Somerset Maugham in his short story "The Portrait of a Gentleman" — essentially a brief review of the book delivered by a narrator who happens upon it being sold by a second-hand bookseller.

Blackbridge himself was a careful poker player, preferring to play for low stakes and minimal risk. (See this earlier "Poker & Pop Culture" installment for more on his book.) In other words, he liked a game that could be considered merely "amusement."

But many — including some of the business world's most serious risk-takers — have approached and played the game differently, and with great seriousness.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Photo: "wall street sign" (adapted), nakashi, CC BY-SA 2.0.