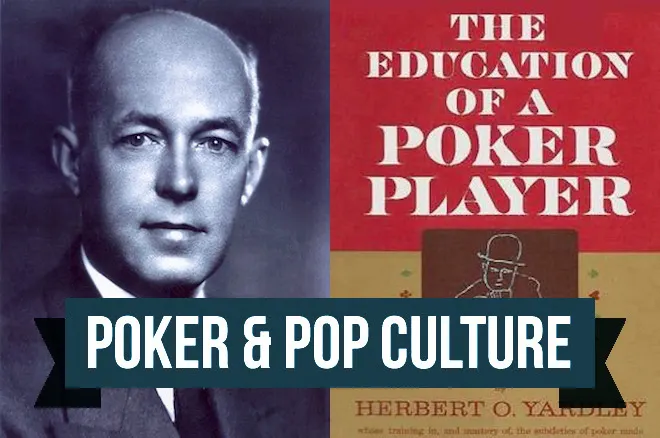

Poker & Pop Culture: Herbert O. Yardley, Code Breaker Turned Strategy Writer

In late 1957 there appeared a book that for an entire generation of poker players would serve as an invaluable introduction to poker strategy — Herbert O. Yardley's thin, hugely influential volume titled The Education of a Poker Player. A bestseller in its time, for many poker players over the next couple of decades it would remain the only poker strategy book they'd ever heard of, let alone read.

The Birth of "Intelligence"

The Education of a Poker Player was not Yardley's first book, nor did it represent his introduction to American popular culture. In fact, the book was published near the end of Yardley's colorful life, well after his days as the United States' foremost code breaker during and after the first World War.

In 1931, Yardley had published The American Black Chamber, thereby communicating to the world details of his role as the founder and head of MI-8, a cryptanalytic organization started by the U.S. shortly after WWI and ultimately dissolved following the stock market crash of 1929. MI-8, also known as the "Black Chamber," is often compared to today's National Security Agency (NSA).

The American Black Chamber was a huge seller for Yardley, though brought with it controversy as it told many secrets the U.S. government did not especially want publicized. In fact, the government considered pursuing legal claims against Yardley for the book's publication, though ultimately did not. However, laws were subsequently passed regarding the publication of governmental records that prevented Yardley from publishing a second book about his time with MI-8.

His services no longer wanted by the U.S., Yardley would later work for both Canada and China as a code breaker before retiring in the 1950s. He began work on The Education of a Poker Player late in life, and indeed the book would appear just a few months before his death at age 69.

A Poker Book of Anecdotes and Advice

The book is both a poker strategy guide and an autobiography, starting with Yardley's life as a teenager growing up in Worthington, Indiana, then moving on to describe his adventures cracking Japanese codes in China with MI-8, all the while passing along specific advice about various forms of poker.

The book is in three parts. The first two are both titled "Three Poker Stories," and both feature Yardley weaving various poker lessons into his entertaining autobiographical tales.

The first part concentrates on Yardley's younger days learning how to play poker in Indiana saloons. The narrative primarily focuses on time Yardley spent at a saloon called Monty's Place. According to Yardley, he preferred Monty's "because it offered more color and action." Also, not insignificantly, of the several saloons where Yardley played poker, "Monty's Place was the only clean one."

"Monty" refers to a man named James Montgomery, described in the book teaching young Yardley how to play variations of five-card draw (jacks or better), five-card stud, and five-card draw (deuces wild with the joker).

Some have suggested the Monty presented in The Education of a Poker Player is in fact a compilation of various people Yardley knew, although the author himself insisted he was an actual person. Along with Monty's game-specific advice comes more general pointers about hand reading, tells, and other psychological issues specific to poker.

The second part of the book presents an older Yardley working as a code breaker in China. Here, Yardley takes on the role of the mentor figure tutoring his interpreter in five-card draw (lowball), seven-card stud, and seven-card stud hi-lo. As in the first part, the chapters (save one) all contain summaries describing highly-detailed hand examples designed to communicate further the strategic concepts being advanced.

A third and final part then offers brief treatments of other, even more obscure stud and draw games such as Doctor Pepper, Baseball, and Spit-in-the-Ocean.

Tight as a Player, Loose as a Writer

Al Alvarez — whose The Biggest Game in Town was discussed last week — once described The Education of a Poker Player as "a funny, vivid, utterly unliterary book" that despite its flaws teaches an important lesson to poker players — always to try to get the best of it, and avoid situations where you cannot.

"Yardley's Law" (as Alvarez puts it) is to "Assume the worst, believe no one, and make your move only when you are certain that you are unbeatable or have, at worst, exceptionally good odds in your favor."

Though tight as a player, Yardley's prose style could also perhaps be described as a bit loose. Here's a taste — it's not Shakespeare, mind you, but not entirely "unliterary" either. In this passage, Yardley reflects on the various characters whom he witnessed routinely passing through Monty's Place:

It is said that sooner or later everyone of any note comes to the Café de la Paix in Paris to sip a drink and watch the crowd. I read somewhere that a detective, looking for a murderer from Indianapolis, Indiana, took up a position at the Café, sure that his man would show up.

Well, the detective might just as well have chosen Monty's Place. To my young mind, everyone of note came there to lose his money — itenerant trainmen, barbers, magicians, actors, jugglers, owners of shows, drummers, coal operators, land speculators, farmers, poultrymen, cattlemen, liverymen. And of course there were the usual town bastards, drug addicts, idiots, drunkards, not to mention the bankers, small businessmen, preachers, atheists and old soldiers. There was also Doc Prittle, the local sawbones, who bragged he'd taken a six-weeks' course in medicine at Prairie City and had a diploma to show for it....

There's something humorously indulgent about Yardley's frequent digressions. While the stories are mostly well told and engaging, they do occasionally exhibit somewhat less discipline than he follows when at the tables.

That's because all of the poker advice does closely follow Alvarez's above-quoted paraphrase of "Yardley's Law." Avoid unfavorable, negative-EV situations, and do your best to let the suckers give you their money. In this way Yardley emulates his mentor Monty, who says he simply will not sit down in a game — or stay — unless he's getting the best of it.

"I figure the odds for every card I draw," says Monty, "and if the odds aren't favorable, I fold. This doesn't sound very friendly. But what's friendly about poker? It's a cutthroat game, at best."

Mr. Cool Plays a Square Game

In the end, Yardley comes off as a cool and worldly James Bond-like figure, with many of the tales from Monty's Place and various backrooms in China helping successfully build a kind of hard-boiled, tough guy ethos for the author. (There's genuinely useful advice about poker, as well, particularly from Monty in Part One.)

Perhaps indicating the public's readiness for a genuine poker strategy guide, as well as its taste for the exotic (and perhaps embellished) tales of international intrigue from a famous American code breaker, the book was an enormous commercial success.

James McManus wrote that when an excerpt from The Education of a Poker Player appeared in the November 9, 1957 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, that "issue broke the newsstand record by selling 5.6 million copies." Speculated McManus, "the Post's vast middle-class readership was apparently hungry for lessons in tough, honest poker."

While other poker books would be written and published over the next couple of decades, Yardley's book was the one most players were likely to have read during that period, if they read any poker books at all.

I remember once speaking to the late Lou Krieger (who'd write about a dozen poker books himself), about how The Education of a Poker Player was the first poker book he'd ever read — and the only for for another couple of decades at least (until Super/System came around).

As far as the history of poker literature goes, then, the importance of Yardley's book is unquestioned. In terms of larger cultural significance, however, The Education of a Poker Player is also meaningful for at least a couple of reasons.

For one, the book signals an early, important moment in the culture beginning to recognize poker as a legitimate skill-based endeavor, with its status as a bestseller standing as a kind of endorsement of poker as a subject worthy of study.

Additionally, for all of the book's intrigue, the focus throughout is on how to beat fairly-played games, thus presenting poker as not only a legitimate test of skill, but a game that is not necessarily overrun by cheaters. There had been earlier poker strategy books, of course (some of which have been discussed here), though many of those tended to present poker as an unreliable game rife with "sharps" lying in wait for unsuspecting rubes. See, for example, "Poker & Pop Culture: Strategy Books Telling How to Play, But Warning Not To."

The Education of a Poker Player presents poker in a different, more favorable light. As McManus puts it, "Herb Yardley helped usher in the age of square poker."

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.