Poker & Pop Culture: Jessup's 'The Cincinnati Kid' More Than Just Pulp Fiction

"The Kid had never been much of a reader, lacking the curiosity and the patience to find out how a character in a book got on with his life, so his perspective was as narrow and as restricted as the world of cards and stud poker."

~Richard Jessup, The Cincinnati Kid

While many poker players and fans know about the 1965 film The Cincinnati Kid — regarded by many as one of the best "poker films" ever made — fewer are familiar with Richard Jessup's original novel published a couple of years previously.

Jessup was born in Savannah, Georgia on New Year's Day in 1925. He grew up in orphanages, then in his late teens ran away to become a merchant sailor, a career he continued until he started writing novels in his mid-20s. In other words, by the time he started writing, he had already traveled widely and experienced much.

He had also already read a great deal. In a 1970 interview Jessup said he "read himself around the world" when working at sea, reading one book per day. According to another story regarding that period, Jessup is said to have typed out all of Leo Tolstoy's lengthy classic War and Peace, then upon finishing tossing it all overboard, providing himself another kind of tutelage for a later career creating his own plots and characters.

At some point Jessup also had a job as a dealer at a gambling joint in Harlem, an experience from which he certainly drew when writing The Cincinnati Kid. Jessup would eventually pen more than 35 novels, including a series of spy novels featuring an operative named Montgomery Nash. He also wrote a number of well-received westerns under the pseudonym Richard Telfair. He died of cancer in 1982.

Jessup would himself no doubt affirm that The Cincinnati Kid is no War and Peace. The book is of modest length (around 35,000 words or so), and like several other of Jessup's works is rightly classified as a "pulp" novel — that is to say, an example of inexpensively produced, commercial fiction designed for mass audiences and usually intended to entertain more than edify.

With a history dating back to the early 20th century and including many popular magazines and pocket-sized paperbacks, such "pulp" productions tended to feature "genre fiction" such as adventure stories, mysteries, romances, tales of science fiction and/or fantasy, westerns, true-life crime stories, war stories, sports-themed fiction, as well as certain varieties of exploitative storytelling (with much sex and violence),

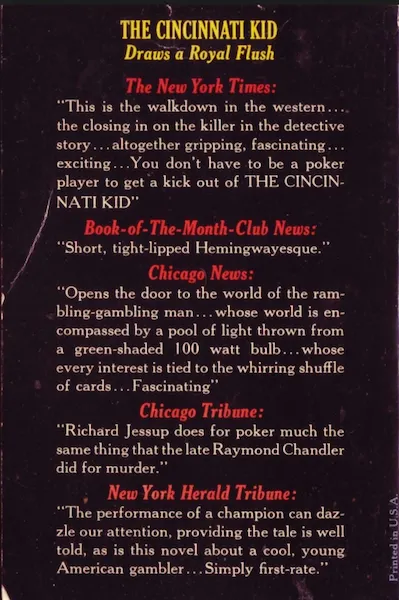

The short book is a rapid read, for most probably not taking much longer to finish than it takes to watch the 100-minute long film adaptation. In fact, a copy of the original pocket-sized paperback (pictured above) is about the size of two decks of cards, though not even as thick.

Jessup's novel is said to have been directly inspired by the 1961 film The Hustler starring Paul Newman (itself an adaption of another short novel by Walter Tevis). The Hustler focuses on a young gun billiards player with a great nickname — "Fast Eddie" — who after early success gambling on his play is motivated to challenge the legendary "Minnesota Fats."

Similarly does Jessup's story present the poker player Eric — a.k.a. "The Cincinnati Kid" — rising up the ranks to take on Lancey Hodges, a.k.a. "The Man." If the reader hadn't already noticed the parallel, a blurb from a review appears above the title announcing how the book "Does for stud poker what The Hustler did for pool."

Another contemporary review of the novel highlighted the book's affinity with other "hard-boiled" fiction by claiming that with The Cincinnati Kid "Richard Jessup does for poker much the same thing that the late Raymond Chandler did for murder."

Both claims are slightly hyperbolic, as the novel is quite unassuming in both its scope and impact. It's also somewhat pales in comparison to the achievement of the later film version directed by Norman Jewison and starring Steve McQueen and Edward G. Robinson (more about that below).

That said, it does introduce poker to a mainstream audience in an engaging way, including affording a glimpse of the high-stakes underground games played by the "rambling-gambling" players who consider themselves full-time pros, circa early 1960s.

The story is set in St. Louis (the film is set in poker's birthplace, New Orleans, while also moving the action back a few decades to the 1930s). Jessup's descriptive style presents a succinct yet wide-ranging overview of the scene and many of the characters who populate it.

The reader is exposed to a lot nifty poker-related jargon here. The loose-aggressive player willing to take risks is described as having a lot of "cock" in him. The player who busts out of a game and must accept a loan from other players has gone "Tap City" (and is not allowed to play again until he's paid back those debts). In five-card stud (the featured game) there is playing "no stay" (i.e., folding), and those players left in the hand vie for "no stay" money (i.e., dead money).

When the players examine new packs of cards by sniffing their wrappers, it is explained they are looking for "the tell-tale odor of a hot iron and a tampered seal." Such details — clearly gleaned from Jessup's dealer experience — significantly add to the novel's verisimilitude.

Jessup also frequently delves into the psychology of poker, carefully establishing the various reasons why poker and nothing else has the potential to satisfy Eric's yearning to become "the Man."

Other pursuits fail him, as do other card games. Blackjack he dismisses as "a game of short bluff and limited scope." "He gave bridge a try, but didn't like the idea of partners." He found craps harmless fun, "but still there was something in him that wanted a game where there was more personal control." At last he comes around to poker, "first to draw poker and then he found stud to be the game that was right as rain."

The story isn't at all complicated, with the first half of the novel setting up the big game and the second half describing it play out. The Freudian implications in the nicknames of the story's two combatants are more than a little obvious, of course. Jessup doesn't shy away from exploring the connection between Eric's wish to "be the Man" (i.e., be regarded as the best five-card stud player) and his struggle to mature into adulthood (i.e., to be a man, and not a "Kid").

As in the film, the novel explores the subplot of Eric's relationship with his girlfriend, Christian, and considers the extent to which that relationship interferes with his poker-related goals. When Eric visits Christian's family (prior to his big showdown game with Lancey), her father quizzes him both about his intentions with Christian and about the importance of his beating "the Man."

In describing this early conflict between Eric and Christian's father, Jessup cleverly overlays a poker analogy, suggesting how Eric — utterly consumed as he is by poker — couldn't help but experience the encounter as being like a "heads-up" match.

"The Kid stared back with his poker face, with his stud face, blank, expressionless," writes Jessup, describing Eric's initial response to the father asking him if he intended to marry Christian. "He did not hurry with his answer as he coolly and calmly ran over the question and examined the percentages."

Eric decides to "raise," responding with a question himself about whether or not the father would object if Eric were to marry her.

From there tension rises and falls, with Eric eventually — carefully — revealing he and Christian had been living together. Jessup describes Eric confirming such news "slowly, turning over his hole card, letting the light of day come upon that secret that, until then, only he had known."

Eventually the men arrive at a kind of mutual respect, with Christian's father also understanding and even agreeing with Eric's declaration that his upcoming match with "The Man" is more important to him than is Christian.

Elsewhere (such as in the epigraph above) we're told how Eric isn't interested in much at all beyond poker. Jessup isn't overly judgmental, but there's an implied criticism of Eric's narrow worldview, and a suggestion at least that he lacks the real-life experience needed to realize his goal of defeating (and therefore becoming) "the Man."

As noted, the film is more successful in most respects, creating an engaging plot with more fully-realized characters while also delivering more affecting messages and themes than happens in the novel. Indeed, if you've seen The Cincinnati Kid and then decide to give the novel a read, one hard-to-avoid effect is to appreciate how greatly improved the story becomes thanks to the additions and changes made by screenwriters' Ring Lardner, Jr. and Terry Southern.

One such change has to do with the most important supporting character, known as "The Shooter." In Jessup's story, the Shooter is more obviously a mentor figure for the Kid, having gone through precisely the same trial at an earlier stage in his poker career. He, too, took his shot at (his version of) "the Man," unable when younger to resist making the attempt.

Now the Shooter has settled into a less-risky, more methodical style of play. Unlike in the film, the Shooter's woman isn't as important of a character (and so there is no subplot involving her). The Shooter is also a much more admirable character here than in the film, one who is clearly respected by others — and deserving of such respect.

A couple of other supporting characters from the film are missing from the novel (the most notable is Slade), although the main plot is all there including the story culminating with a huge climactic hand between the Kid and the Man.

In fact, the novel adds one more chapter following the big hand, showing what happens next to the Kid over the subsequent months. The film's decision to omit this epilogue is another good one, I think most would agree.

Despite its flaws, Jessup's The Cincinnati Kid does an entertaining job of presenting poker to a wider audience, making the game interesting to readers who have enough curiosity and patience to sit down and read a book about the game and its players.

One of my favorite passages, in fact, comes when Jessup is describing people who are curious about poker — namely, those who come to the hotel room where the Kid and the Man are playing.

Some who come to watch are "lovers of the game... [who] never played more than a quarter and a half." Others "talked low and spoke of percentages and odds as though they were reciting beads in church." Still more "found it all culturally beguiling and sociologically interesting," people "who had never seen big-time gamblers before and who looked around bright-eyed and said very little even when they were talking with their mouths wide open."

The passage not only seems to describe the varied audience Jessup was aiming to capture with his book, but also shows an awareness on Jessup's part of the different levels of familiarity and commitment people have when it comes to poker — an observation that still rings true today.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.