Poker & Pop Culture: Frederic Remington's Cowboys, Cards, and Carnage

We've been considering a number of different cultural productions inspired by poker during its early history, including stories (true and fictional), songs, articles, and early films. Many of these creative responses to America's most popular card game were not only inspired by it, but the most popular of them would in turn help shape opinions regarding poker going forward.

Another example worth including as we continue our transition from the 19th to the 20th centuries is the significant contribution of the American artist Frederic Remington whose paintings, illustrations, and sculptures of the Old West would help shape how that era would come to be remembered.

Remington exerted direct influence not only on how the Old West "looked" to his own and future generations, but what it "meant" as well, with his imagery and depictions of the American cowboy inspiring early Western films and contributing to an Old West mythology that continues to have its effect today.

Among Remington's works were a couple of especially popular ones depicting card playing in that Old West context, and those, too, would have their influence when it came to poker's reputation and place in the culture.

The Rise of Remington

Remington was born in New York in 1861 at the start of the Civil War. His father was a Union colonel, and young Remington would be similarly nurtured early on for a military career himself. However a talent for drawing would carry him down a different path that included a short stint at art school at Yale University during the late 1870s.

As a young adult Remington was able to to travel west and see many of the landscapes and scenes he'd spend his later life reproducing, getting involved early on with the popular Harper's Weekly where his first drawings were published. More schooling back in New York followed, and by the age of 25 he'd scored his first Harper's Weekly cover, a sketch of a scout tracking Geronimo amid the decades-long Apache Wars.

Other early highlights for Remington included being recruited to illustrate future president Theodore Roosevelt's 1887 book Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail, then doing more traveling out west and witnessing first-hand the aftermath of the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee from which he'd produce numerous paintings and illustrations.

A one-man show at the American Art Galleries furthered his fame, and by the end of the century Remington had become one of the country's best known artists, even having a couple of his paintings appear on postage stamps. At the start of the new century, he'd reunite with Roosevelt while serving as a war correspondent and illustrator for the New York Journal during the Spanish-American War.

During the years preceding his premature death from complications with appendicitis in 1909, Remington wrote novels, sculpted, and continued to paint and sketch despite the popularity of his naturalistic style starting to wane as more impressionistic artists began to enjoy greater notice.

Filling in Details of the Mythic Cowboy

Remington's legacy was particularly felt when it came to later depictions of the American cowboy in the Old West by other artists as well as in fiction, movies, plays, and later television shows. One series of his titled The Evolution of the Cowpuncher (1893) had special influence, a collaboration with the fiction writer Owen Wister best known for his 1902 book The Virginian often pointed to as the first ever "Western novel" (about which we'll have more to say later).

From these images and stories steps the mythic cowboy, based in reality though embellished in various ways when made into the central protagonist of later fictions. He's a figure who is manly, tough, athletic, and possessed with an understanding of the importance of work and how to survive. Such self-sufficiency mirrors the fiercely independent spirit of the nation itself, for which in many of these stories he's made to stand as an emblem.

Also — think John Wayne if it helps — he has a sense of justice, can be hospitable and/or serving of the cause of justice, is full of gravitas and takes a no-nonsense approach to most issues, and is capable of violence when needed. Meanwhile in such narratives are Indians made to serve as the "other," with other ideas — including the relative status of men and women and "gender roles" — firmly established and reinforced as well.

Poker playing becomes part of the mythic cowboy's character, too, adding an element of intelligence and acumen to the portrait. In Cowboys Full, James McManus notes how "mastery of poker and of guns were widely viewed as twin gauges of masculine know-how."

Interestingly, when looking at Remington's famous illustrations of Old West poker games, the cowboy's violent side is front-and-center, with two works in particular depicting the "before" and "after" of card-playing conflicts.

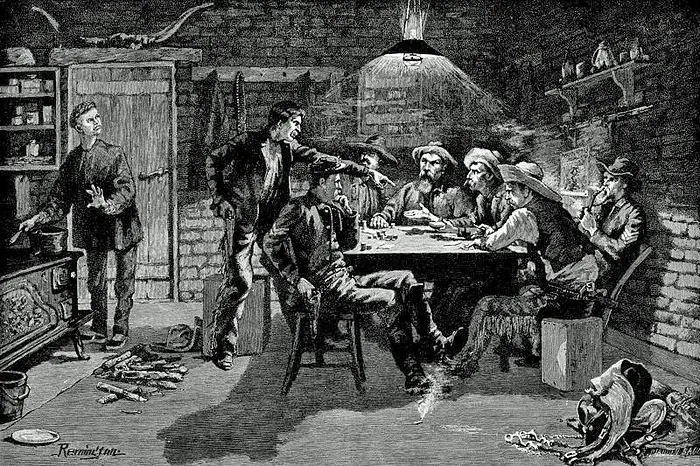

A Quarrel Over Cards (1887)

Remington's woodblock print titled A Quarrel Over Cards — A Sketch from a New Mexican Ranch first appeared in the April 23, 1887 issue of Harper's Weekly.

Though darkly-lit, the scene is a vivid one, showing seven men gathered around a crowded table covered by chips and cards. The one standing points aggressively, his finger directed toward another seated and holding a deck of cards. The suggestion is clear — the accuser has detected a problem with the dealing, while the accused responds defensively, his open palm conveying innocence.

Others look on with concern, with a servant at the stove holding a hand upwards as if in anticipation of the argument taking a more threatening turn. Meanwhile the player nearest to us in the foreground — whom we perhaps only notice later — studies the scene carefully, one hand rubbing his cheek and the other firmly grasping the pistol in his holster.

And oh, look — the man standing — his hand is on his gun as well.

The accompanying text in Harper's describes the scene even further, explaining how the man on the dealer's right is his confederate. "It was his deal before, and then the trick was done," that is, the stacking of the deck. We're also directed to notice the player on the dealer's left who is hastily covering his chips, having "a shrewd suspicion that in the 'muss' the table might be overturned."

The description insists the scene is typical, and characterizes all poker games of the day as both crooked and prone to violence. A game of "draw-poker," we're told, is rife with cheating, either by a dealer acting in concert with another player or cards being saved from the deck and produced thereafter. "A hidden card produced at the exact nick of time, makes 'four of a kind,' and the pot is raked in," goes the explanation.

But occasionally players are wise to such deceit. "Sometimes," we're told, "there comes a player who... knows all the ways which are crooked. It even adds to his zest to play not only against the luck of the cards, but the talents of the gamblers." Gunplay is therefore to be expected — "there would be little excitement about the game without drawing of cards and revolvers."

In other words, the writer concludes, "Mr. F. Remington has made a typical gambling scene." Readers who have never seen such a game are assured the picture "is something that happens somewhere or other every day in the Territories."

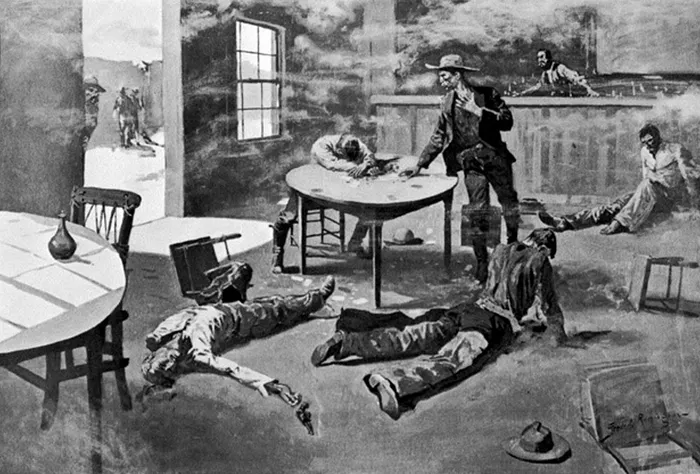

A Misdeal (1897)

A decade later Remington produced a painting titled A Misdeal, capturing in oil on canvas what could be read as a kind of sequel to the earlier work.

Less needs to be said regarding this scene, in which the phrase "four of a kind" unfortunately could be used to refer to the dead or wounded — three on the floor, one at his seat. As the bartender and those outside the saloon cower, the aggrieved party appears in the process of collecting the session's final pot.

Though perhaps again meant to present a typical gambling scene, the painting wasn't that typical for Remington who more often focused on outdoor settings and didn't necessarily highlight frontier violence, even when illustrating some of the battles he'd witnessed. In any event, as with A Quarrel Over Cards, the painting helped establish the impression of poker being a dangerous game, furthering the association of such carnage with card playing.

Proving Remington's influence on later filmmakers, one of the great Western director John Ford's early silent films, Hell Bent (1918), opens with a character looking at and admiring A Misdeal. Then later does the film move into depicting violence similar to that captured in the painting.

As we've already begun to note, the turn of the century saw poker find its way into other, less dangerous contexts such as clubs and private homes, where the "typical gambling scene" often wouldn't include such deadly disagreements.

Next week we'll look at the work of another American painter — one of Remington's contemporaries — presenting much more playful quarrels over cards. Hint: the players play hands with paws.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.