Sorting Out the Law Behind Phil Ivey's Edge Sorting Debacle at Borgata

PokerNews contributor and East Coast-based attorney Maurice “Mac” VerStandig is an expert on the American gaming scene.

Well-versed in online casino management from common issues of fraud and theft prevention to the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act and Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, VerStandig has a strong background in bankruptcy work and is also skilled in the strategic valuation and monetizing of complex assets.

He applies that knowledge to all areas of his practice, from fraud recoveries to traditional insolvency proceedings. Here, VerStandig takes a look at the Borgata lawsuit against Phil Ivey and offers his opinion on its chances of success.

There is a marked irony, bordering on outright hypocrisy, underlying the Borgata’s lawsuit against Phil Ivey, his associate Cheng Yin Sun, and Gemaco, Inc., as a casino openly in the business of exploiting statistical advantages has filed a legally hyperbolic, seemingly overreaching, complaint against a couple of players who may have also been in the business of exploiting statistical advantages.

To be sure, the Borgata appears to have a very real case against Gemaco, a playing card manufacturer that is apparently not very good at manufacturing playing cards, but the Atlantic City casino’s claims against Ivey and Sun strike as too richly imaginative to withstanding judicial scrutiny, and ultimately serve to only soil the relative ethos of an otherwise robust pleading against Gemaco.

For those not familiar with Ivey and Sun’s scheme (the details of which Ivey has openly acknowledged in the context of another case at an unrelated casino), the duo first took to Crockfords — a swank British gaming parlor — and then the Borgata — the only New Jersey casino even vaguely close to being “swank” — for a series of marathon sessions of Punto Banco and Baccarat.

Different nomenclature notwithstanding, these are essentially the same game. And while not as iconic as poker, online blackjack or craps in the modern gaming lexicon, baccarat has long been among the most regal of betting events, even playing prominent roles in Dr. No and Casino Royale, acting as a second fiddle only to a certain beverage that ought not be stirred.

The actual rules of baccarat are relatively unimportant, other than to recognize that it is a pure game of chance dealt with a standard 52-card deck, that the house edge is narrow, and that baccarat players have a long and tawdry history of introducing some truly bizarre superstitions into gaming parlors.

Gently blowing on the dice at a craps table is downright sensible behavior compared to some of what goes on in baccarat pits on a daily basis, and casinos are remarkably adept at making sure their prized gamblers not realize just how absurd they look engaging longwinded philosophical conversations with the deuce of clubs.

Just like blackjack and poker, baccarat is a game largely reliant upon the dizzying uniformity of cards yet to be turned.

In the same manner one would check kings on the river if he or she knew for certain an opponent was holding pocket aces, one imbued with knowledge of the next card to be dealt could wreak utter havoc on a game of baccarat. And, as is now rather clear, Ivey and Sun just so happened to be imbued with that knowledge.

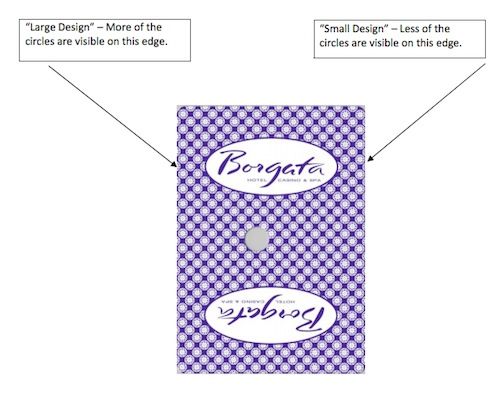

The key to this particular magic trick is known as “edge sorting,” which really amounts to little more than the strategic exploitation of inconsistencies in the way patterns on the back of playing cards are cut.

Many houses, these days, have a white border around their playing card patterns, in large part to block against this precise scheme; the Borgata, for one reason or another, did not.

And, apparently, if one looked closely at the back of a Bortgata baccarat deck, he or she could see inconsistently cut patterns, revealing larger images of gems on one side than another.

Ivey and Sun realized this, sat for marathon sessions of baccarat, and ensured cards were turned such that certain favorable members of the deck had backs facing one way, while others faced the opposite way, according to the lawsuit.

To make this work, the Borgata alleges, a few oddities were required: First, Ivey specifically requested these Gemaco cards. Second, an automatic shuffling machine had to be used (which, evidentially, ensures cards not be turned from one side to another, as a human dealer might do in washing a deck before a manual shuffle).

Third, the dealer had to speak Mandarin Chinese — a language in which Sun is seemingly fluent.

At a poker table, the introduction of conditions such as this would send up more red flags than a May Day parade in Tiananmen Square. But in the superstition-laced world of baccarat, these demands actually register as somewhat mild on the scale of relative voodoo.

According to the lawsuit, Ivey and Sun played four sessions at the Borgata in 2012, ultimately taking down $9,626,000 in winnings before the casino began to sense that something may be amiss.

The final session, in September of 2012, was awkwardly tempered by word spreading that Crockfords was withholding payment of monies putatively won by Ivey, in a game of Punto Banco, because it believed he had been edge sorting.

The Borgata actually theorizes, in its suit, that Ivey may have started to intentionally lose hands once he knew the New Jersey casino was wise to his British troubles, as he apparently went from being up over $3 million on the trip, to ultimately leaving with the relatively meager $824,900 in profit.

With this background, the lawsuit should be viewed as two claims — one against Ivey and Sun, and one against Gemaco.

The latter is decidedly less enticing in nature, and accordingly unworthy of much ink herein, but it bears noting that this set of claims actually seem rather robust — Gemaco allegedly sold the Borgata non-uniform cards; the Borgata lost just under $10,000,000 to a player who exploited this lack of uniformity; law and reason alike support the suggestion that Gemaco likely acted negligently and breached a warranty or two along the way.

By contrast, the claims against Ivey and Sun are much murkier.

Putting aside, momentarily, the actual form of these claims (which is touched upon below), there is something of a metaphysical grey area at the heart of this case.

On one extreme end of the spectrum is a player who uses loaded dice in a craps game — this individual, if caught, is destined for time in a local cell block, as well as a rendezvous with the civil justice system.

On the other extreme end of the spectrum is a player who knows how to count cards in blackjack and crunch numbers through a six-deck blackjack shoe — this individual, if caught, will be kindly asked to leave the premises, allowed to keep his or her winnings, and revered in the halls of MIT.

Edge sorting falls somewhere between card counting and weighted snake eyes — and the law is yet to figure out just where.

There is no real precedent for cases like this, and when the judicial system cannot find precedent, it goes in search of analogy — something that does not much help here, either, because edge sorting is not truly analogous to anything other than an honest game of three-card Monte, and that is something of an oxymoron unto itself.

One of the more amusing aspects of the lawsuit is that the Borgata, clearly trying to tie edge sorting to the slot-fraud end of the spectrum, alleges Ivey and Sun to have utilized a “cheating device,” which is expressly illegal under New Jersey law.

Of course, that does not truly strike as humorous until the complaint reveals what this “cheating device” was — the automatic shuffler.

Yes, that automatic shuffler — the one owned by the Borgata, presumably acquired from a manufacturer of regulation gaming equipment, and the one used every day to make sure a hybrid generation of card counters not be able to follow specific cards through a manual shuffle.

Admittedly, I am not a judge, nor am I a New Jersey lawyer (though I work with many of them at Offit Kurman), but I cannot reason how a casino’s own automatic shuffler can be deemed a “cheating device” without making a mockery of either the gaming industry, the legal profession, or both.

This is tantamount to a Yankees pitcher crying foul when a line drive is hit back at his chest — the medical staff may prove momentarily sympathetic, but an umpire is almost certain to just let out a chuckle and direct the next batter into the box.

In total, Ivey and Sun face 12 counts in this lawsuit, many of which are highly technical, and a few of which appear to be just plainly inapplicable.

Claims for fraud in the inducement, breach of contract, and breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing all strike as particularly far-fetched; the suggestion that a casino can be fraudulently induced into dealing a card game with its own cards, equipment, and personnel, is seemingly fantastical; the theory that a contract — express or implied — underlies games of baccarat is similarly perplexing; and the hypothecation that the covenant of good faith and fair dealing — something normally invoked in arm’s length business transactions — covers the mercenary-rich environment of a casino floor, where both the player and the house are unapologetically out to win the other’s money, is likewise baffling.

Similarly, claims for violation of racketeering laws are not likely to survive a well-drafted motion to dismiss.

The racketeering laws, about which I have previously written on this site, were originally drafted to aid in mafia prosecutions, and have morphed over time into a sort of “super fraud,” capable of ensnaring true criminal organizations.

These claims rarely withstand even the slightest of scrutiny, and the allegations of this case certainly do not strike as sufficiently egregious to deviate from this rule.

Other claims are interrelated, which is to say that certain claims depend on the success of others to survive. And, at core, most of these lose all oxygen if a court finds, as I suspect it will, that 1) there is no contract between a player and a casino; 2) a casino deviates from its own well-oiled protocols at its own risk; and 3) exploiting house vulnerabilities is not a form of “swindling and cheating” any more than an automatic shuffler is a “cheating device” (please cast aside memories of one particularly memorable scene in Ocean’s Thirteen, and appreciate that no one is alleging Ivey or Sun to have planted a corrupt shuffler in the Borgata).

One claim, however, deserves greater attention — not for its merit, but for its dangerous hypocrisy.

The Borgata has brought suit for unjust enrichment, an old common law claim that is frequently introduced in civil litigation across the United States. T

he core “elements” of this cause of action are only the enrichment of one party, at the expense of another, with knowledge, in a situation where equity dictates the monies lost should be returned.

There are few finer examples of the wholly subjective realm of equity jurisprudence than this claim, and it is a favorite of lawyers who believe sympathetic facts and clients can sway a judge into awarding monies because such is, in essence, the right thing to do.

Here, however, the tolerance of a claim for unjust enrichment would be a self-inflicted dagger in the heart of American gaming.

The Borgata is in the business of unjustly enriching itself, just as is every other gaming hall in the country.

Flashy signs meant to induce gamblers into sucker bets or real money slots, deceptively simple games with well-masked house advantages, and the whole façade of a casino itself — from maze-like infrastructures, to free drinks, to playing chips that exist in large part to help people forget real money is being gambled — are textbook examples of one party (the house) enriching itself at the expense of another party (the player), in circumstances that are far from equitable.

Stated otherwise, the Borgata needs to be cognizant that this sword has two edges — if Ivey and Sun can be held liable for unjust enrichment in a gaming hall, it should not be long before hoards of hungry attorneys looking to make a name for themselves start bringing suit against the Borgata (and other establishments) for the same cause of action.

And while the easy answer seems to be that the Borgata holds a license that permits it to operate public swindles, few things are so clear cut.

Recent news of a man bringing suit against a casino for allowing him to lose money while intoxicated garnered soft laughter, aimed mostly at his seemingly hopeless lack of perception, but if the Borgata succeeds here, suits of that nature, once thought frivolous, may be prone to suddenly start surviving motions to dismiss.

Finally, a technical note.

Since this suit was filed, the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey has issued an order requiring the Borgata to file an amended complaint, and a few have looked at this as the court being overly eager to scold the Borgata for a sloppy claim.

In all fairness to a pleading that frankly deserves little credit otherwise, the flaws that led to this specific order are both common and hyper technical; they do not relate to the merits of the casino’s claims, and instead deal only with finite constitutional issues of federal jurisdiction.

I have seen multiple orders like this in my own practice, over the past few years, and long ago learned to credit them as little more than ministerial directives.

*Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily of PokerNews.

Maurice “Mac” VerStandig, Esq. is the managing partner of The VerStandig Law Firm, LLC, where he focusses his practice on counseling professional poker players, sports bettors and advantage players across the United States.

He is licensed to practice law in Maryland, Virginia and Florida, as well as in nearly a dozen federal courts, and regularly affiliates with attorneys licensed in numerous other states and jurisdictions. He can be reached at [email protected].

In this Series

- 1 Ivey Claims He Used "Edge Sorting" in £7.8 Million Lawsuit With Crockfords

- 2 Top 10 Stories of 2013: #10, Ivey, Kagawa, Smith, and Others Face Legal Trouble

- 3 Borgata Files $9.6 Million Lawsuit Against Phil Ivey for Alleged Baccarat Cheating

- 4 Details Emerge in Borgata's Lawsuit Against Phil Ivey

- 5 Sorting Out the Law Behind Phil Ivey's Edge Sorting Debacle at Borgata

- 6 Phil Ivey Files Motion to Dismiss Borgata Lawsuit, Claims Win Was "All Skill"

- 7 Ivey's Edge-Sorting Accomplice, Cheng Yin Sun, Files Lawsuit Against Foxwoods

- 8 Breaking Down the Legality of Cheung Yin Sun's Edge-Sorting Lawsuit Against Foxwoods

- 9 Phil Ivey to Discuss "Edge Sorting" Lawsuits on 60 Minutes

- 10 Phil Ivey Loses £7.7 Million "Edge Sorting" Court Battle Against Crockfords Casino

- 11 Phil Ivey Appeals Against Crockford’s Ruling

- 12 Top 10 Stories of 2014: #2, Phil Ivey Endures More Legal Drama

- 13 Judge Rules Borgata Lawsuit Against Phil Ivey Can Proceed

- 14 Phil Ivey Appears in Car Commercial for 2015 Chrysler 300

- 15 Foxwoods Survives Edge Sorting Lawsuit from Phil Ivey's "Queen of Sorts" Accomplice

- 16 Phil Ivey Files Countersuit Against Borgata Regarding $9.6M in Baccarat Winnings

- 17 Highlights from Ivey/Borgata Deposition: Booze, Pretty Cocktail Waitresses and More

- 18 Borgata Contests Phil Ivey Counter-Claims

- 19 Ivey Granted Permission to Appeal £7.8 Million Edge-Sorting Case Against Crockfords

- 20 Phil Ivey's £7.8 Million Appeal in Crockfords Case Began Yesterday

- 21 Court Opinion Split on Phil Ivey's $9.6M Baccarat Win

- 22 Phil Ivey Contests Borgata Request for His Baccarat Winnings

- 23 Court Orders Phil Ivey to Return $10.1M to Borgata

- 24 The Mysterious Year for Phil Ivey

- 25 Poker Pro Phil Ivey Will Try to Appeal Borgata $10M Ruling

- 26 UK Supreme Court Grants Phil Ivey Permission to Appeal Crockfords Case

- 27 Phil Ivey Loses £7.7M Supreme Court Appeal in London Edge Sorting Case

- 28 Top 10 Stories of 2017, #7: Phil Ivey Loses $19 Million in Court Battles

- 29 Gemaco Playing Cards Off the Hook in Borgata Ivey Edge-Sorting Debacle

- 30 Phil Ivey Looks to Delay Payment of $10.1M to Borgata

- 31 Phil Ivey in Danger of Losing More to Borgata

- 32 Borgata Given Clearance to Seize Phil Ivey's Nevada Assets

- 33 Film Based on Phil Ivey's Baccarat Partner Cheung Yin “Kelly” Sun in the Works

- 34 Report: Borgata Seeking Phil Ivey's WSOP Winnings Plus $214K Interest

- 35 Report: Borgata Secured Phil Ivey's $50K PPC Winnings

- 36 Ivey Borgata Case Takes Another Turn as Cates and Trincher File Objection

- 37 Ivey Versus Borgata Continues With Legal Proceedings