About That Dotted Line... Attorney Maurice "Mac" VerStandig on Horrell vs. Attack Poker

An expert on the American gaming scene, Maurice “Mac” VerStandig is well-versed in casino management from common issues of fraud and theft prevention to the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act and Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. With a strong background in bankruptcy work, VerStandig is also skilled in the strategic valuation and monetizing of complex assets, and applies that knowledge to all areas of his practice, from fraud recoveries to traditional insolvency proceedings. Here, Verstandig takes a look at the contract dispute between Ken Horrell and Attack Poker, which you can read about by clicking here.

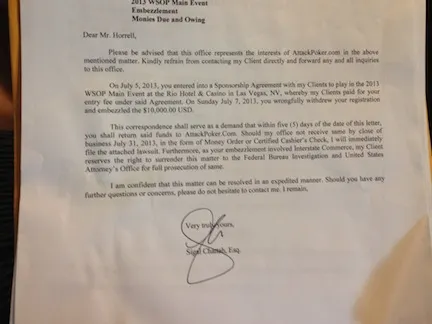

In a saga of apparent deceit begetting apparent deceit, it is as easy to root for Kenneth Horrell — the satellite-dominating Hawaiian who earned a coveted seat on poker’s grandest stage — as it is to cheer on AttackPoker.com — the increasingly-popular gaming hub that was seemingly snookered by a Jeff Spicoli look-alike. As reported here by Chad Holloway, the cyber operator has summoned Mr. Horrell to a rendezvous with the courts, and between nine counts for relief is seeking to collect a sum potentially in excess of $40,000. Meanwhile, the defendant has now gone public with a version of events suggestive of his greatest flaw being a failure to look beyond the scantly-clad models of AttackPoker.com and into the rigid text of a now-infamous contract*.

*You can view the entire contract by clicking here.

Concerning that contract, the once-chic Latin doctrine of caveat emptor — literally, “buyer beware” — strikes as an all-too-apt punch line to this parable. As Mr. Horrell tells the story, his online birth into the Main Event nearly hit a snag as he found himself debating between taking the $2,500 cash option or raising funds sufficient to trek to Vegas in hopes of ESPN glamour. When he arrived in Sin City, his recollection goes, he was afforded the quintessential high roller treatment by Attack Poker, only to soon find himself deciding between two contracts — one allowing the typical World Series of Poker appearance sans future engagements, and the other taxing his potential winnings, but intimating that additional sponsored events were as ascertainably nearby as a Nevada desert mirage.

In the grand pass line tradition, Mr. Horrell pressed his bet. And regardless of what the satellite winner thought, hoped, or inferred, the reality is that he affixed his name to an agreement providing, among other things, “Except as to the Entry Fee (the ‘Compensation’), Talent shall not have any other or further right to any compensation pursuant to this Agreement.” The Hawaii resident was, of course, the “Talent,” and while many a juror may take pity on a lay person forced to sign a contract on the fly, the reality is that this crucial clause is not relegated to fine print, is not buried in a rider or addendum, and is not particularly rife with the variety of legalese notorious for deceiving the public at large.

Buyer’s remorse rarely strikes as quickly as here, but somewhere between inking this contract rife with ambiguities and seeing dealers shuffle up and deal, Mr. Horrell wised up to the reality that he had traded a percentage of winnings for a thoroughly non-binding offer to consider potentially staking him in future tournaments. At this juncture, he would have been wise to consult counsel — as any attorney worth his or her billable rate surely would have offered a few deft words on the doctrine of rescission, helped the misguided card shark walk back his errant move, and negotiated the standard arrangement of an entry fee coupled with sponsor advertisements, allowing Mr. Horrell to lay exclusive claim to any monies won.

Yet it seems Mr. Horrell steered clear of legal counsel and instead devised a scheme of his own: Withdraw the $10,000 entry fee, skip the tournament, and flee the mainland for the territory James Cook once affectionately deemed the Sandwich Islands. While it is difficult to ascertain just what thinking guided this course of action, surely it must have seemed that two distinct options lay in the muck — either there existed a loophole through which the $2,500 buyout could be neatly parlayed by a factor of four, or the scheme at bay would prove ultimately actionable.

And actionable it was. Mr. Horrell now faces a nine-count lawsuit, seeking a return of the creatively-laundered $10,000 and various other fees and damages that could increase that sum more than four-fold. In the District Court of Clark County, Nevada, AttackPoker.com has alleged the kitchen sink, and while many of the nine causes of action are likely to wither in the early stages of litigation, there is a substantial likelihood that the online gaming entity will soon be looking to domesticate a judgment in the 50th state.

The nine civil claims at issue are breach of contract, breach of the covenant of good faith and fair dealing, monies due and owing, conversion, punitive damages, quantum meruit/unjust enrichment, promissory estoppel, declaratory relief, and fraud. By definition, these cannot all survive a trial – some must fall victim to the idiosyncratic definitions of others, and some are likely to fall victim to inapposite facts — but the lawsuit should nonetheless be viewed as carrying a hefty collection of claims.

The first claim — breach of contract — is perhaps the most self-explanatory of the bunch. Yet, ironically, it may be amongst the more difficult to prove. Attack Poker’s complaint does not allege with any particularity just which provision of the contract was breached by Mr. Horrell, and there certainly does not exist any clause demanding he not cash out an entry fee pre-tournament (likely, of course, owing to the once-inconceivable nature of these facts). There is a marginal argument that section 2(a)(i) of the agreement – providing the defendant shall “Become an Attack Poker TEAM PRO member for purposes of participating in the World Series of Poker” — has been violated, but a judge may well parse this verbiage en route to finding that the obligation was solely to become an Attack Poker team pro, and that the “purpose” is not so much a requirement as an underlying motivation.

Yet this vulnerability is almost assuredly familiar to Attack Poker, as the claims for quantum meruit/unjust enrichment, and promissory estoppel, are all of such a nature as to afford relief in the absence of a contract. In fact, under long held common law principles, these theories of law are only permitted to operate where a contract does not bind the relationship between a plaintiff and a defendant. It is difficult to surmise just how quantum merit — a Latin theory normally used to secure wages for employees without contracts – plays into this case, but unjust enrichment is the legal method of walking back a wrongful taking of monies, and promissory estoppel is the legal method of imposing a contract where a clear agreement exists but certain facts are not governed by anything in writing. If AttackPoker.com busts on its breach of contract claim, look for these two claims to become paramount.

Conversion, by contrast, is the sort of claim likely to amuse legal pundits to an entirely too perverse degree. I am not a Nevada attorney and do not profess any knowledge beyond the boundaries of those states in which I hold a license to practice law, but conversion is a common law claim — suggesting it to have more to do with the evolution of British jurisprudential concepts than anything drafted by a Nevada legislature — and it is notoriously difficult to implement in cases where cash has gone missing. In short, conversion is the civil version of legal theft — a plaintiff alleges that a defendant took (or “converted,” as it is) his or her property, and that the plaintiff should either have the property returned or be paid its fair value. The hiccup, which is all-too-familiar to any attorney who has been called upon to assist a client with wrongfully-emptied coffers, is that conversion is almost always inapplicable to cases where the missing “property” is money. Here, though, one of the more esoteric exceptions to this general rule might actually apply — there is a line of legal reasoning that holds conversion is a workable claim if the money in question is a particular, identifiable, sum of money otherwise dedicated for a distinct purpose. And a WSOP entry fee certainly appears to jive with this caveat (save for one massive issue — it was not Attack Poker’s money when Mr. Horrell took it, but more on that below).

Pay little heed to the claims for monies due and a declaratory judgment — these are each perfunctory redundancies unlikely to garner momentum in the absence of another claim proving successful. And do not obsess over the claim for punitive damages, either — this is not so much a cause of action as a freestanding enhancement to other causes of action; AttackPoker.com will need to win elsewhere for this portion of its complaint to prove useful.

But do pay appreciable heed to the claim for fraud, as that stands to be the most devastating portion of this case. While there are few hard and fast rules, Mr. Horrell is unlikely to be called to task for the payment of punitive damages (monies meant to punish him, as opposed to monies meant solely to make AttackPoker.com whole) if he is not ultimately found liable for fraud. Punitive damages are simply not a common accessory to the other theories advanced in the complaint — people are rarely summoned to forfeit an essentially-moral penalty for breaching contracts or unjustly enriching themselves.

All of these claims, however, suffer from a series of vulnerabilities. And while it does seem Mr. Horrell is more likely than not to find himself on the wrong end of a civil judgment, three distinct issues may prove sufficiently obstructive to aid him in wiggling out of this legal bind, or at least various parts of it.

First, and most importantly: it is not entirely clear that AttackPoker.com has been damaged. In civil proceedings, a plaintiff must show not merely that he, she or it has been wronged — a plaintiff must, too, show that this wrong has caused some variety of actual damages (and hurt feelings do not nearly suffice). It is easy to surmise that AttackPoker.com was damaged here by losing $10,000, but the specifics of this case intimate otherwise – the stack of high society had already been paid over to the WSOP as Mr. Horrell’s entry fee, and, as such, had long since departed the plaintiff’s bank account. If the defendant had shown up to play, moved all in on his first hand, busted out, and caught a flight back to Hawaii, AttackPoker.com would still be out its $10,000 and would have no bona fide claim for damages. So to prove damages, it will have to show that it expected something out of Mr. Horrell’s tournament play – and as far too many card players know, expecting to cash in the Main Event (let alone making the cut on ESPN and being able to flaunt those ghastly patches of corporate propaganda) is always a difficult proposition laced with chance, luck, and fortunate turns of the river. This could well be the end of Attack Poker’s case — or at least the majority of its case (as the unjust enrichment and promissory estoppel counts could conceivably eek by this obtrusive hurdle).

Second, and far less critically: do not expect AttackPoker.com to recover its attorneys’ fees, notwithstanding its clearly asking for them in the complaint. A doctrine known as the “American Rule” carries the day in most courts of the United States, and under this occasionally-frustrating theory, plaintiffs are always made to bear their own legal fees, regardless of the outrageous nature of a defendant’s conduct, unless some statute or contractual provision provides otherwise. Here, the contract in question has a lot to say about who pays the lawyers if a third party sues Mr. Horrell or AttackPoker.com for some reason related to their partnership, but it is silent as to who foots the bill if the two sue each other.

Third, and most creatively: Mr. Horrell might just be able to get out of this contract after all. To be sure, the odds are long, and the following theory is laced with gunfire aimed squarely at the moon, but I have won cases on stranger lunar shots. In short, the law forbids what are known as illusory contracts — agreements where one party is bound to a definite course of action, and the other party is bound only to consider taking a correlative course of action if it feels like so doing. Mr. Horrell’s paramount gripe is that AttackPoker.com was not actually bound to stake him in any future events — it was to take a cut of his winnings in the WSOP in exchange for its agreeing to maybe, kind of, sort of, perhaps, speculatively, think about considering sponsoring him down the road. Now, the stake money should prove enough to satisfy the requirement that it be obligated under the agreement. But if Mr. Horrell can cleanly show that Attack Poker was already bound to stake him (per his winning the satellites), and that he did not need to sign a contract to come into $10,000 in the form of an entry fee, he might just be able to convince a sympathetic judge that he ought not be held liable.

Yet before this matter proceeds, there is one other issue worthy of attention: $10,000-$40,000 is what many attorneys deem a nightmare lawsuit. For truly small cases, people can represent themselves and sometimes survive. For relatively small cases, a number of lawyers are adept at minimizing court filings and appearances, so as to keep legal fees within reason. And for large cases, legal fees tend to pale in comparison to the monies at stake. But when it comes to a matter such as this, with issues as distinct as those presented here, few good lawyers will be able to navigate the waters of Mr. Horrell’s saga for less than $10,000 in legal fees, and Mr. Horrell is only going to make a bad situation worse if he hires someone who is not a good lawyer. This, of course, is one of many reasons why settlements exist — and this is the strongest indicator that the saga at hand could well be resolved out of court.

Of course, Mr. Horrell already had a chance to resolve this out of court. But his decision to skip the $2,500 cash out and to hop that destiny-bound flight for Sin City has placed him in the same category of all-too-many Nevada vacationers: facing a bill far greater than that for which he bargained.

*Photos courtesy of Ken Horrell.

Maurice “Mac” VerStandig, Esq. is the managing partner of The VerStandig Law Firm, LLC, where he focusses his practice on counseling professional poker players, sports bettors and advantage players across the United States. He is licensed to practice law in Maryland, Virginia and Florida, as well as in nearly a dozen federal courts, and regularly affiliates with attorneys licensed in numerous other states and jurisdictions. He can be reached at [email protected].

Get all the latest PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us both Facebook and Google+!