Bob Hooks: The Forgotten Texas Road Gambler

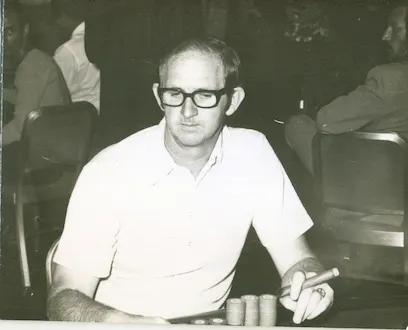

“Seat open.” It’s a common poker expression Bob Hooks has heard and barked out countless times going back to his days as a Texas road gambler and then later as the poker room manager at Binion’s Horseshoe during the first World Series of Poker. The 84-year-old is no stranger to poker, even if the game has passed him by. But today is a new day. Today, Mr. Hooks is getting a new chair.

Whatever figurative sentiment might be read into that, the reality is that on this otherwise ordinary East Texas day, inside, in the Best Western hotel room that Mr. Hooks now calls home, a space has been cleared for the delivery of a brand new La-Z-Boy recliner. While the hotel’s manager and Hooks’ de facto caretaker, an eye-catching blonde named Kristi Michels, readies the room for the new piece of furniture, Mr. Hooks lingers in the hotel’s lobby with a cup of coffee in his hand, eyes firmly fixed to the East.

His sleepy gaze is the kind formed by years of staring down the white lines cutting through the surprisingly lush Texarkana plains. No matter which direction he turns, Mr. Hooks can recall a story, and more often than not it’s a decades-old poker tale long lost to history. To the East — which is today’s focus — is Shreveport where he tangled on countless occasions with T.J. Cloutier and Doc Ramsey; behind him to the West lie the bright lights of Las Vegas, a path previously pioneered by Benny Binion. If he were to look South, Hooks might recall the miles he racked up chauffeuring Johnny Moss to Waco; and to the North is where Hook’s own story began.

Texas

Texas

- Live Poker is allowed

- Online Poker is forbidden

- Online Casino is forbidden

- Sports Betting is forbidden

The Grand Old Man, Boss Gamblers & a Poker Education

Located 10.3 miles north of his hotel hospice, Edgewood, Texas, is Hooks’ true home. That’s where he was born on August 18, 1929, the first of Alex and Inez Hooks’ four children. His father, a well-respected baseball coach at Southern Methodist University (SMU), once played first base for the Philadelphia Athletics and also at one time held the state record for the shot put.

“Daddy would get the shot put and he would throw it all the way [along his walk] to school — about 2.5 miles — and all the way back,” Hooks recalls. “That’s how dedicated he was.”

Like many young boys in small towns, Hooks longed for adventure. In Edgewood, a dry county to this day, adventure came in the form of bootleg liquor and poker. When he was 16, Hooks learned about both and took advantage of the former to excel at the latter.

“I had no car, no bicycle, no shows, no TV, no nothing,” Hooks relates. “I’d see these guys going out in the woods to play cards. So to get away from home I’d go out and watch them play. This one guy would come and let me watch. That’s how I got started. Every one of them would get drunk but I never did. When the game was over, I’d have [all] the chips because they drank.”

One time, Hooks won $16 in the game. That might not seem like a lot, but in 1945, for a 16-year-old boy, it felt like life-changing money. With his father on the road, Hooks returned home to share his fortune with the family.

“I go home and there’s Jerry, he’s my little brother, two years younger, and James, he’s 10 years younger,” Hooks says. “I come in and I’ve won $16. You’d have thought I won $16,000. I went into the living room and said, ‘Y’all come on in here to the bedroom.’ I threw that $16 on the bed and said you get what you want. James didn’t get nothing, you know, he was just six years old, but Jerry, who turned out to be the banker, got two or $3 of it. That $16, I thought that was all the money in the world.”

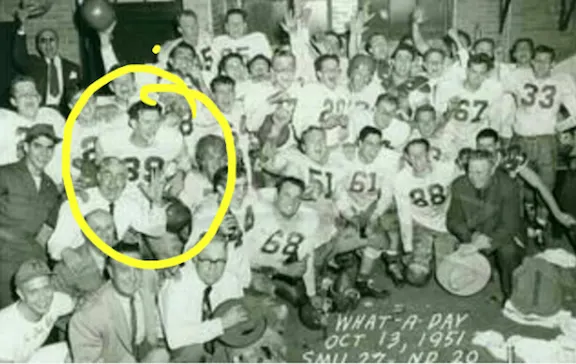

Six years later, Hooks’ younger sister Mary was born. By this time he had followed in his father’s footsteps and made his way to SMU on a football scholarship. During his time on the team, the SMU Mustangs upset the fifth-ranked Notre Dame Fighting Irish 27-20 in an October 13, 1951 game that was ranked as the 16th greatest moment in SMU Football History — an accomplishment Hooks recently relived when the Dallas Morning News ran his team photo in their paper. Looking back, this is one of Hook’s proudest accomplishments.

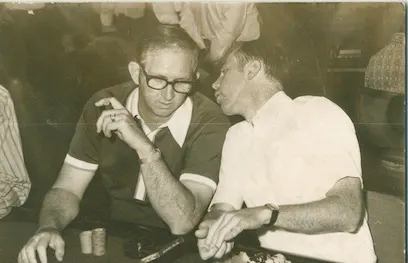

It was also at SMU that Hooks met upperclassman Kenny Smith, who became a noted chess player and one of poker’s first true characters (every time he won a pot he’d doff a top hat he claimed was from the Ford Theater the day Lincoln was shot and proclaim, “Whatta Player.”). Together, the pair embarked on a lifelong friendship that included a fair amount of time spent at poker tables.

One memorable hand between them took place at the AmVets, a poker club Hooks opened in Dallas. According to the lore, Hooks limped into the pot only to have Smith put in a big raise. Hooks, who held pocket kings, then three-bet all in and Smith went into the tank for more than three minutes. When Hooks couldn’t take it any longer, he grabbed Smith’s cards, saw that he had two aces, and put Smith’s chips in himself.

“That’s a true story,” Hooks recalls with a laugh. “There wasn’t any more decisions and he was aggravating me. He’s got the nuts, the world knows it, and he was sticking it to me. [That was the way] we ribbed each other.”

After graduating from SMU, Hooks returned to Edgewood and began life as a family man and poker player, though he kept his occupation under wraps. “In a little town like that, ain’t nobody know I gambled when I was young,” Hooks says. “A poker player was like a bootlegger.”

Hooks married his wife, Cynthia Gready, in December 1952, and they had four children — Bobby, Larry, Catherine and Ronnie. In his early 20s, Hooks finally got a car to call his own, and he put it to good use, becoming a Texas road gambler. Over time he developed a reputation as a solid player, and before long some of the game’s best took notice, including Doc Ramsey.

“Boss gambler” refers to the head honcho of the poker scene in any particular area. These days it’d be players like Phil Ivey and Daniel Negreanu, but back then players were notorious more than they were famous. In regards to Ramsey, boss gambler is a term Hooks uses with great respect.

“Hooks, how old are you?” Ramsey asked when the two first encountered one another in a game down in Tyler.

“Twenty nine,” a brash Hooks replied.

“Twenty nine,” the 65-year-old Ramsey repeated. “Wish I had your age.”

“Well,” Hooks retorted, “I wish I had your money.”

A lifelong friendship was born in that moment, one that even resulted in Ramsey staking Hooks in his early days. Ramsey passed long ago, but Hooks remembers his friend fondly: “Everywhere you went he was the top cream.”

Hooks would know too, because he really did go everywhere. He played in nearby Dallas and would then head down to Houston followed by a quick jaunt to Long View — which doesn’t even take into account his out-of-state excursions. The miles seemed endless, but that’s what was required to stay in action. “Nowadays in one block you can find that many games,” Hooks reflects.

Hooks also went to a game every Monday night in Waco. That’s where he first met Johnny Moss, a Poker Hall of Famer who won nine WSOP bracelets including three Main Event titles. Moss became known as the “Grand Old Man of Poker,” and it was a well-deserved nickname.

“He was my hero, the best player around,” Hooks says. “I listened to everything he said. He wasn’t welcome in some places because he was so good, but they couldn’t turn him away because everybody wanted to play with Johnny Moss.

“He took a liking to me. I’d take him every week to Waco. He would swap me 10 percent. As time drew on, he wanted to swap quarters. I was getting to where I was a little bit better of a player I guess. Soon, people were calling me Johnny Moss’ boy.”

After more than a decade traveling the Texas circuit, Hooks and a partner opened the renowned AmVets Post No. 4 at 308 ½ South Irving Street in Dallas in 1969. It was an illegal operation, but because they were chartered under the AmVets ruse, the game’s rake was justified — generally 5-10 percent of the pot — as necessary to cover club expenses. Hooks ran the club successfully for a year, but eventually sold to Byron “Cowboy” Wolford in order to head out West.

From the Texan Plains to the Nevada Desert

Legend has it that Poker Hall of Famer Felton “Corky” McCorquodale introduced the game of Texas hold’em to Sin City when he started a $10/$20 limit hold’em game at the Golden Nugget, but before he did, he and Hooks had become fast friends.

“Ask me a question on who the best player is and I’m going to say Corky. Uncle Corky, goddamn,” Hooks says of McCorquodale, who would only don suits from Neiman Marcus. “That’s a high-dollar suit down here,” Hooks clarifies.

Unfortunately his friendship with McCorquodale didn’t sit well with Moss. As Hooks tells it:

“I’m gonna tell you something ain’t nobody else know. They didn’t care for each other. You know what Moss and them used to do to him? Corky would get broke and they would stake him. They’d give him $5,000, go to the hotel game, and he would win. He’d win $6,000, give them $3,000, and keep $3,000. Now after two or three months, he’d have his bankroll built up to $40,000-$50,000. They didn’t cheat him, you know what they did? They’d buy him Old Forester. I know what kind of whiskey he drank, and [they’d get him] a bottle. Johnny would get him drunk and win all his money. That don’t make Johnny bad, but Corky was so helpless it wasn’t even funny. Corky, I love that man. He always said to me, ‘Hooks, let your word be your bond.’ Truer words were never spoken.”

Around that time news made its way back to Texas that the games in Vegas were too good to miss. Hooks wanted to go, but he couldn’t convince Moss to go with him.

“We ain’t going out there. It ain’t worth nothing out there,” Moss said flatly. Hooks abided Moss’ command for a month, but the lure of Glitter Gulch was strong; Hooks eventually went without his mentor. As it turned out, Moss was unwelcome in Vegas. Apparently, he had borrowed money from singer Tony Bennett and failed to pay it back. Bennett, as the story goes, had connections to the mob, so Moss’ failure to pay him did not result in a welcome mat being rolled out.

So how did Moss later make it to Vegas and establish himself in the poker pantheon? According to Hooks, it was all thanks to one man — Benny Binion.

“You didn’t want to fuck with the outfit — I call them the outfit or the Italians — unless you were Benny Binion. Anyway, Benny loaned them $2 million one time and he never had any problems with them after that. So Moss got Benny Binion to smooth it over. The reason he was able to do it was that one afternoon in come two ‘security guards’ from the Dunes. Jack Binion said they came down to get money. He said [the mobsters in charge of the Dunes] were broke. They had a junket that came in from New York. Binion said the dice had been hot for about two hours and the junket players won all of the Dunes’ money. Now they’ve got money in the bank, but the bank ain’t open. They called Benny to see if he had any money on hand, which he always did. Plenty of it I guess. I’ve been down in the room, a big old room with silver dollars, money stacked everywhere like hay. They walked out of there [with the $2 million], and from then on they [the Binions] never got any [trouble] from the outfit.”

Hooks continued to travel back and forth from Dallas to Vegas, and on one such junket Moss introduced him to Benny. The three met at the coffee shop at the Horseshoe, and Moss told Binion, “Y’all are hiring, here’s who you need to hire right here.”

Moss’ word carried a lot of weight with the patriarch, and the next day Hooks was offered a job. It wasn’t something Hooks asked for nor necessarily wanted. “Binion called me the next day and [offered me a job]. I had a family, farm, cows, and was hustling every which way to make a living, which was hard to do in those days,” Hooks says. “He called me, this was on Friday, and he said, ‘I’ll give you a call on Monday and you let me know.’ I said, ‘Whoa, whoa, I haven’t even talked to my family yet.’ It was hard because all my family was there in Edgewood. I had four kids.”

Hooks continues: “I was playing at the Redmond Club there on South Irving in 1970 and the phone rang. He said, ‘Well, have you thought that over?’ I said, ‘No sir.’ He said, ‘Well think before we hang up.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’ll take it.’ I didn’t know what I was making, didn’t know what I’d be doing. I knew I was going to be a boss, I knew that. I went out there within the next couple of days, moved in still not knowing what I’d be making.”

Before he left for Vegas, Hooks needed to tell his wife, kids, and kinfolk — all of whom had just moved into a new house. It wasn’t a negotiation, but a notice. With his family’s “permission” acquired, Hooks relocated to Vegas and immediately got to work on the graveyard shift.

“They wanted me to learn how to make the schedules, how to hire, and what they did when they caught them cheating. There was a lot of that going on in those days,” Hooks recalls. Indeed, cheating was so commonplace that even Hooks’ good friend Moss was involved.

“He had a girlfriend in Alabama,” Hooks says of the married Moss. “I’m not sure how to say this, but she’d help him get in cold decks. He wasn’t an angel. There weren’t many angels back in those days. She had tits this big. I’d never seen them that big in those days. She’d flop one of them out and all six of the players would be looking and bingo, you got aces.”

Even though cheating was rampant, Hooks was tasked with curbing it. “I’d go up there and they’d show me how they cheated. I wanted to know so I could protect players’ money.”

Learning the Vegas Ropes and the 1972 WSOP

In all his time working in Vegas, Hooks never saw a paycheck. He had free room and board, but all his wages were sent straight back to his family in Edgewood. On the other hand, as long as he had a poker bankroll, he could keep himself flush with spending money.

“One time I got broke playing a Las Vegas hero. I was just a country boy. He had 15 people around him, and it was just me and Jack [Binion]. Well, he broke me. I knew I could beat him. There weren’t a lot of people I knew I could beat, but he was one of them. I don’t have a big ego, but I knew I could beat him. My daddy had given us some stock, so I told Jack [Binion] I needed $3,000. I said, ‘I’ve got some stock I’ll let you have.’ Jack said, ‘No, you come on back to the table.’ He sent me $10,000. That was my first taste of big money. I asked for $3,000 and he gave me $10,000. He had a little confidence in me. Sure enough, I finally broke [the guy]. I never will forget that.”

Another thing Hooks got a taste of in Vegas was drugs. Of course it was commonplace back then, so much so that one of the world’s most infamous drug dealers, Jimmy Chagra, played in many of the high-stakes poker games.

“There was just so much money,” Hooks says of the drug culture. “Kids were getting like $10,000 for one kilo, 2.2 lbs. It was just everywhere. Girls had it, bosses had it, I can tell you people who had it, myself included. I sampled it. A lot of movie stars did it. Anybody who had money. You could go into a bathroom back then late at night, and someone would ask, ‘You don’t happen to have a bump do ya?’”

“I was playing dice one time out at the Sahara. There was this one lady at the craps table, bless her heart, she was about my age. I was about 50 then. We were going to shoot the dice. She was the only one at the table. She was shaking the dice, and bingo, out came out one of those little brown, amber looking vials that you put cocaine in. It just bounced right out on the table. The stickman kicked it right back to her and they kept on playing.”

Nowadays such a mishap might land a person in the slammer, but this was the early 1970s — which was also when Hooks left the Horseshoe to serve as an Executive Host at the Golden Nugget under Steve Wynn.

“One reason that Steve Wynn hired me, he wanted higher players,” Hooks says. “The Golden Nugget was way, way down there, and he was envious of the Horseshoe.”

Hooks had made dozens of connections in the poker world, so it wasn’t surprising to see some of the game’s biggest names, like Thomas “Amarillo Slim” Preston, visit him at the Nugget — always with a quid-pro-quo attitude of course, wanting a comped room or some other freebie.

“I said go on over to the Horseshoe, them your cowboy friends,” Hooks explains. “He said, ‘I’ve got a girl out there.’ I said, ‘Well, that don’t have nothing to do with me.’ I said to go on over to the Horseshoe to get a room. Well he did, and he came back with this long face. He said, ‘Bob, don’t tell nobody but that was a gay person. I went to kiss her and I found out she wasn’t a girl. Now don’t tell anybody.’ I said, ‘I’m not going to tell anybody until I get to somebody I know.’”

Hooks’ association with Amarillo Slim went deeper than a simple transvestite encounter. Hooks was there in 1972 when the fast-talking Texan “won” the WSOP. Eight players entered the Main Event that year, and a dilemma arose during three-handed play between Amarillo Slim, Doyle Brunson, and Puggy Pearson.

“Didn’t anyone want the title of champion because there wasn’t any money for it,” Hooks explained. Indeed, being a professional poker player in those days was far from glamorous. Brunson didn’t want his name in the mainstream media, Pearson was indifferent, and Amarillo Slim, well he was a showman.

“Me and Jack got up in his office to decide who to give it to. He said, ‘Who do you think?’ I said, ‘Well, I know who wants it the worst, and that’s Amarillo Slim.’ We ended up giving it to Amarillo Slim. He wants to be it, he brags all the time anyway. He couldn’t wait to get it. He thought more of himself than the majority of people.”

With the decision made, Brunson was allowed to cash out due to “exhaustion,” and Pearson and Amarillo Slim put on a show before the latter “won” the title. It was a disreputable turn of events, but of course the WSOP wasn’t held to any sort of standard in those days. Besides, Amarillo Slim proved a wise choice as he cherished the attention and set about making the talk show rounds, which included numerous appearances on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. Without a doubt, he did more to promote and recast poker in a positive light than anyone who had come before him.

Hooks Misses Out on Poker Immortality

By 1975 the WSOP Main Event had grown to 21 players, but it was still played in a winner-take-all format. Hooks played that year, as did his roommate and fellow Texas road gambler Brian “Sailor” Roberts. The pair managed to make the final four alongside Crandall Addington and Aubrey Day, and it was at that point the idea of a deal was brought up.

“Aubrey said, ‘Let’s just all count down and keep all we’ve got.’ I said, ‘No, you’re going to have to play,’” Hooks explained. “Of course he got knocked out. Now Crandall, he’s got that new suit and Sailor’s got a hole in his shoes. I only had like 19,000 and I’m raising every pot. I’ve got two sixes, Addington bet, and I called him. The board came Kx6x2x, and he’s got KxQx. Bingo, I hit three sixes and there he goes. Well, I broke him, and me and Sailor tried to chop it but Benny Binion stopped that because he thought it’d make [the tournament] less authentic.”

Unfortunately, neither Hooks, who had sold a quarter of his action to Jack Binion, nor Roberts wanted the title of World Champion. “You talk about tight, you can’t get any tighter than we were,” Hooks said. “Didn’t either one of us want to win it. He had his reasons, and the IRS was after me all the time.”

Unbeknownst to Binion, the two struck a secret deal to split the $210,000 prize and played it out. “We gave them a good show,” Hooks said. “The hand I got broke on*, it was a legitimate hand. The hand he beat me on was all legit. It looked so good. It turned out you couldn’t have put a cold deck in any better.”

*Hooks couldn’t recall the details of the final hand, and the only thing the record books show is that Hooks lost with the J♣9♣ to Roberts’ J♠J♥.

Finishing runner-up in the WSOP Main Event would haunt some people, but that wasn’t the case with Hooks. For him it was all about the money, and he had struck a deal for his fair share.

“That’s what gets me more than anything. [Some people] would rather have a bracelet than a million dollars,” Hooks says when asked about missing out on the bracelet. “I can’t believe the egos of some people. All Sailor and I wanted was the money. Let us get out of here, you know what I mean. Good gosh, trophies and all that.”

Big Wins, Bookmaking & Befriending a Notorious Killer

While in Vegas, Hooks spent a year working at The Flamingo under Sam Boyd. One night, Hooks was at home (in an apartment owned by Boyd) after working a long shift and decided to head back to the poker room to check out the action. The high-stakes game had broken by that time, but Boyd lingered hoping to reclaim some of his losses.

“C’mon Hooks, you might as well get the rest of this,” he said. Hooks obeyed, taking a seat in the game, and promptly relieved his boss of his last $60,000 — his biggest-ever win. By comparison, Hooks’ biggest loss was for $76,000 at the craps tables — a thrashing he contributes to a combination of liquor and a two-timing woman.

Eventually being so far away from home and away from his family wore on Hooks. “I guess I was homesick,” he admits. “My family was back there and at the age where they needed their daddy there. They didn’t want to come out to Vegas. I should have made them come out I guess, but you can’t raise a family without being there with them. My daddy taught me that.”

With Benny Binion’s blessing, Hooks moved back to Dallas to open a bookmaking and craps operation, a business that proved extremely fruitful when Hooks applied the knowledge he’d gained in Vegas.

“Wasn’t no payoffs, but ain’t nobody get in our way,” Hooks says. “I made them shut the door down at 2 a.m. so the husbands couldn’t stay out all night and cause trouble. I tried to help with the law.”

Of course, cheating and the threat of robbery were always part of the business, but Hooks had both covered. “I wasn’t in with them, but I wasn’t against them either,” Hooks says of the cheaters. “They showed me the courtesy of leaving when I was there most of the time. Basically, there were some good guys, but there’s always bad ones anywhere you go.”

One of the bad ones was R.D. Matthews, a long-time associate of Binion’s that reportedly did wet work in Cuba and was embroiled in the JFK assassination as an associate of Jack Ruby. Out of respect, Hooks paid Matthews 25% of his profits, and that in turn provided him unendorsed protection.

“Baddest son of a gun, but when he knew that I knew the Binions, ain’t nobody looked at me crossway,” Hooks grins. “He came in one night to play and put his pistol down on the table. Drunker than hell he was. We were playing five-card draw lowball and he was drawing three cards (laughs). Every Friday, I’d look him up and give him 25 percent.” Hooks says it matter-of-factly — that’s just the way it was.

Hooks Nowadays

Even though Hooks left Vegas, he continued to visit his home away from home by frequently running junkets back and forth from Dallas. More times than not, these junkets coincided with the WSOP, which was held in May back in those days. Hooks played in the WSOP throughout the mid-eighties, but he never replicated the success he had in 1975. In fact, the records show that Hooks doesn’t have a single WSOP cash to his credit.

As Hooks sits in the hotel lobby, his eyes become resolute. “I don’t know whether I could win [today] or not,” Hooks says as he downs the last of his coffee. “It’s too different, the way the tournaments are. I see these guys make some plays that I just don’t see how in the world they put their money in there. They know something that I don’t know. That’s when I realized I didn’t know how to play [the game nowadays].”

That’s not to say Hooks doesn’t give it a go from time to time. In early 2012, Hooks was actually staying at the Winstar Casino just across the border in Oklahoma. Hooks had used his history with Steve Wynn to secure a position as a room ambassador, which required him to bring in clientele and keep the games thriving. In exchange, Hooks was provided with a free room. It wasn’t a bad arrangement, but eventually Hooks’ failing health inspired him to seek out his doctor back in Edgewood.

It was during that return visit that Hooks spent the night at the Best Western. After visiting with his doctor, who informed him that he had a deteriorating hip and a fluid build up in his knee, Hooks took the opportunity to see some friends. Being back home suited him just fine, so after decades on the road, Hooks opted to settle down. As to what’s become of his family, Hooks is a bit reticent to share. There’s an unmistakable sense of regret and misfortune that clouds his eyes, but he does say that many family members have reentered his life.

As far as Vegas and his high-rolling lifestyle are concerned, those days are squarely in his rearview mirror. It’s been 20 years since Hooks last visited Vegas, and 15 since he’s conversed with his old pals Jack Binion and Doyle Brunson. While paying a visit to his past may not be in the cards, Hooks passes the time the same way he has for years. He still enjoys making and taking a bet, and occasionally antes up in a poker game at the local country club. However, neither of those things is on today’s agenda. Now it’s time to empty his mind of old memories and take a seat in his brand new chair for an afternoon nap.

“I’m not a saint, but I’ve been this long doing what’s right,” Hooks said before setting down his coffee cup and turning towards the door. “I’m going to go the rest of the little spell I’ve got doing the same thing. Yeah, I’m gonna do that.”