Thoughts About the Tournament Bell Curve

I had a driving question when I began researching Tournament Poker for the Rest of Us — is it better to play a tight game or a loose game when we have a deep stack?

For years I had been following a relatively tight strategy, waiting for strong hands to play until my stack got short. Many pundits recommend this "cash game" approach, but others swear by a looser, "chip-up or go home" strategy. Both philosophies have rational arguments in their favor, and world champions have come from both camps. But which approach is actually better?

Cash Game Variance

We can study how our playing style affects variance by analyzing hand histories from online cash games. Chapter 4 in Tournament Poker for the Rest of Us shows that our variance (in big blinds per 100 hands) increases when we play more hands. It also increases when we raise more often. We also expect higher variance if we continuation bet, semi-bluff, or float more often. Generally, our cash game variance correlates to how "active" we are throughout the play of our hands.

However, our cash game variance is not inherently connected to our profitability. For example, the most profitable online cash game players have the highest preflop aggression ratio (PFR% / VPIP%), which means that raising is more profitable than limping or calling. Yet there is no correlation between cash game variance and aggression ratio. So increasing our cash game variance does not make us more profitable.

Tournament Variance

Tournament variance is trickier to study. We can't simply use tournament chips won as a study variable. Cash game chips always have the same value, identical to the cash they represent. But tournament chips are just a bookkeeping tool, changing value as the tournament advances. So we must analyze tournament variance in a different way than we do for cash games.

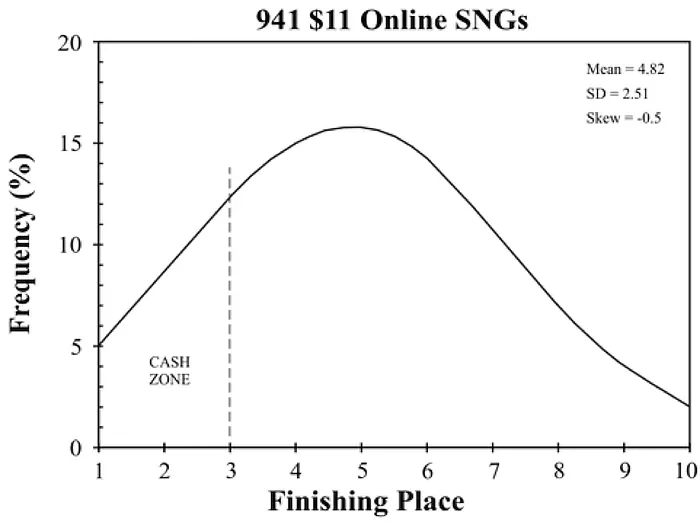

Instead of considering variance in terms of BBs / 100 hands played, let's study the variance in our tournament finishing place. Figure 1 below shows the finishing places for 941 identical sit-n-go tournaments I played several years ago. This is clearly a bell curve, skewed somewhat toward the profitable end. My average place in these tourneys was 4.82 with a standard deviation of 2.51 places.

The key aspect of this curve is that I won money only when I finished in the top 3 places. There is no difference in profit between finishing 4th place and 10th place. This key aspect of tournament poker does not apply to cash games, and is why our cash game strategy must be modified for tournaments.

Tournament ROI

Maximizing our ROI (Return on Investment) should be the fundamental goal for tournament poker. We might like to convert this into an hourly rate, but our ultimate aim is to win as much money per tourney as we can.

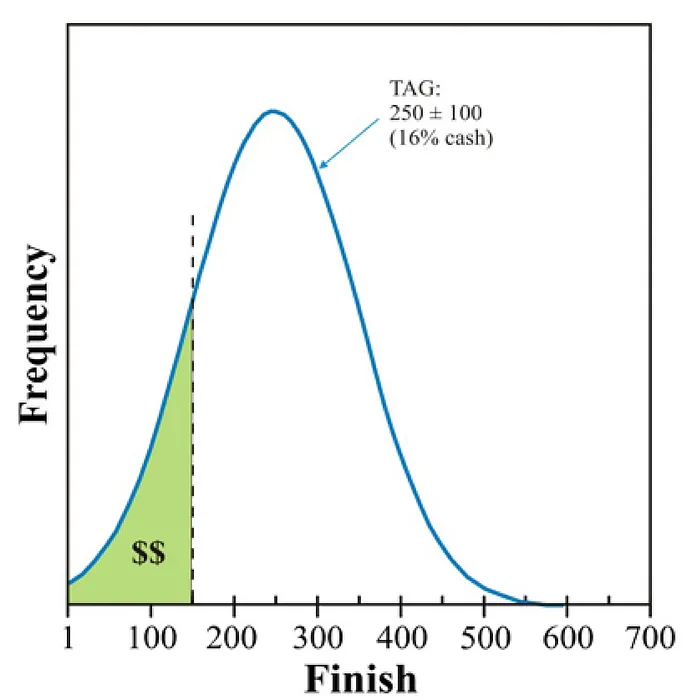

Suppose we play a large number of 1,000-player tournaments with identical structures and plot how often we finish in each place. We might expect a curve similar to the TAG curve in Figure 2. (This is just an idealized version of Figure 1.)

The only profitable finishes (the top 15 percent) are to the left of the dashed line, shaded in green. So how do we increase our tournament profit? The usual way is to learn to play better. This would shift the bell curve to the left, widening the green profit region by increasing the number of profitable outcomes. This is what we aim to do by studying strategy columns and videos, though it's never an easy path.

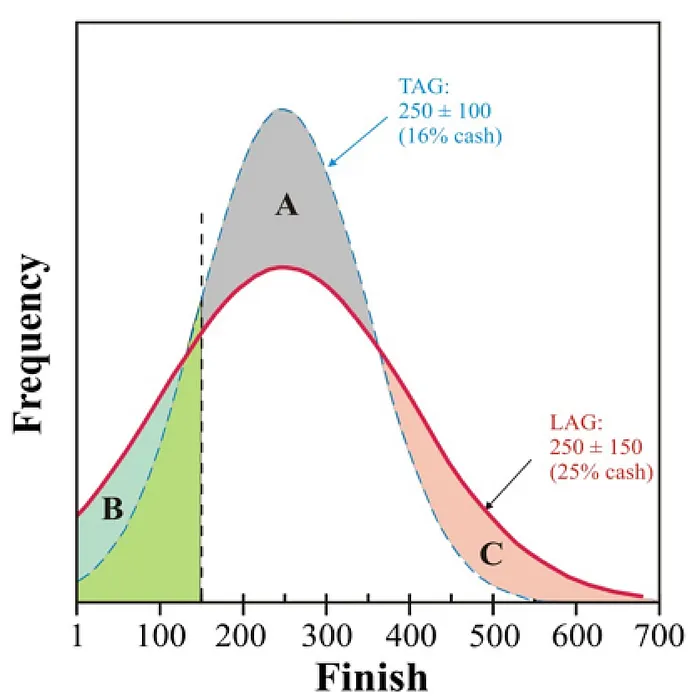

But this isn't our only option. We can change our playing style from a TAG style to more of a LAG style by being more active. This increases our variance, which widens our bell curve. Figure 3 shows how this would work.

Our average LAG finish is the same 250th place, but our standard deviation has increased to 150 places by playing a more active style. This has the effect of shifting some of our finishes from the "A" region to the "B" and "C" regions.

Moving some of our finishes from A to C does not impact our profit at all since all of these finishes are losers. But moving some finishes from A to B improves our ROI by increasing the number of finishes in the money. In this example, Mr. TAG cashes 16 percent of the time while Mr. LAG cashes 25 percent of the time. Additionally, more of Mr. LAG's cashes are deeper, further improving his profit.

This is the essence of the "chip-up or go home" playing philosophy.

Making Negative Chip-EV Decisions Can Be Good

The above analysis shows that we can improve our ROI by widening our bell curve without shifting the peak. But we can also improve our profit even if our peak shifts to the right.

In a cash game, we generally strive to avoid making any negative chip-EV decisions. This is because chip-EV in a cash game is the same as dollar-EV; a negative 0.1 BB chip-EV decision creates an actual loss of profit. Additionally, many cash gamers will forgo small positive chip-EV plays simply because they don't seem worth it.

But this is not true in a tournament. A negative chip-EV decision can be worth positive dollars if it widens our bell curve enough to overcome its shift to the right.

For example, calling a preflop raise with 9-7 suited is usually a losing play in a small stakes Vegas cash game. Suppose we deem our call to be worth -0.1 BBs in the long run. Then we should then fold it. Indeed, we should fold all such negative-EV opportunities because they add up to a loss in long term profit.

Suppose we are in the same situation in a tourney with the blinds 100/200 with 100 BB stacks, and we deem our call to be worth -20 chips in the long run. But we should call since a big flop can lead to a significant increase in our stack, which increases our chances to cash. On the other hand, losing 20 chips out of our 20,000 chip stack will have little impact on our average tourney finish.

Our call widens our bell curve without significantly shifting its peak, which is essentially trading a small chip-EV deficit for increased tournament variance. If you think about it, there are many opportunities to make such a trade. Making small negative chip-EV decisions in a tournament can be a good thing.

Conclusion

My initial question was whether my tight playing style was superior to a looser "chip-up" strategy for playing NLH tournaments. It is now clear to me that widening my tournament bell curve will lead to greater profit, even if my bell curve peak shifts to the right. To accomplish this I must increase my variance.

I can do this by playing more hands preflop, and playing them more aggressively. I can do this by c-betting and floating more often. I can do this by calling down more often with second pair. I can do this by more often donk-bluffing with a draw. In general, I increase my variance by playing more hands and by taking more chances during every phase of those hands.

Since adopting this new style, my tournament results have improved dramatically, though the sample size is still small. Nevertheless, I am no longer uncertain about which style is better.

Steve Selbrede is the author of six poker books: The Statistics of Poker, Beat the Donks, Donkey Poker Volume 1: Preflop, Donkey Poker Volume 2: Postflop, Donkey Poker Volume 3: Hand Reading, and Tournament Poker for the Rest of Us.