All I Really Need to Know About Poker I Learned From Sherlock Holmes

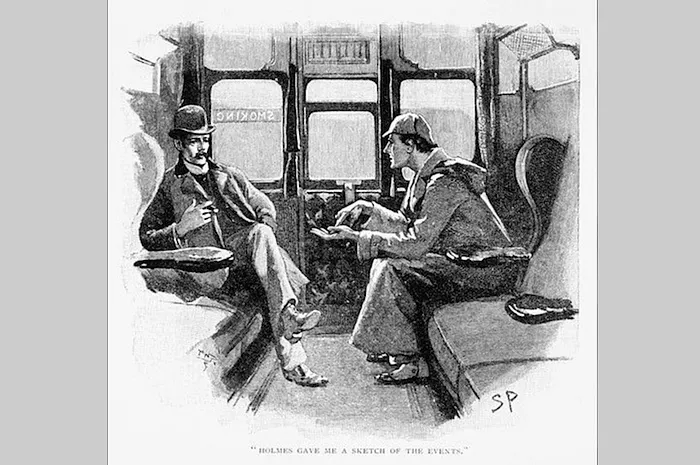

Earlier this week, Nate Meyvis shared his thoughts about some poker books that have held up well over the years. I, too, have read much of the poker “canon,” including older books like Herbert O. Yardley’s The Education of a Poker Player and Doyle Brunson’s Super/System as well as the latest titles from Two Plus Two. But when not too long ago I reread the Sherlock Holmes stories by the great Arthur Conan Doyle, I realized that the world’s most famous consulting detective had a lot to teach me about poker, too.

There is a lot of Holmes to get through, I grant you — 56 short stories plus four novels. And the game of poker is explicitly mentioned just once, in the 1914 novel The Valley of Fear, set in the American West where poker flourished. But rather than specific discussion of the game, it’s the approach of Holmes — his mindset — that is useful to the poker player.

For example, in the first of the short stories, “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Holmes says to his friend and chronicler Dr. John Watson

“You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear.”

Holmes is describing his approach to detection, but the line’s application to poker cannot be more obvious. You “see” things at the table all the time, but how often do you “observe” them? That is, how often do you actually use the observation to your advantage?

You might “see,” for example, a player make an overbet in early position. But what’s key is to observe that he makes that overbet in early position with a hand with which he wants no action (for example, a pair of sixes) or that he overbets to represent a small hand when he actually has AxAx.

In the same story, Holmes counsels Watson that

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

It’s the second sentence that is particularly apt for poker players.

Say you have a big hand, like a set, but the board is dangerous, and there’s all kinds of action on the river. Your (generally correct) instinct is to fold. But you hate to lay down a set, so you theorize your opponents are bluffing, and you “twist facts” to make your theory work. The facts are right in front of you. Put them to work to make the right decision — then make it!

In the “The Five Orange Pips,” Holmes notes

“A man should keep his little brain-attic stocked with all the furniture that he is likely to use, and the rest he can put away in the lumber-room of his library, where he can get it if he wants it.”

Your “brain-attic” should be stocked with the knowledge (“furniture”) you’re likely to need, like commonly encountered odds and probabilities or shoving and reshoving ranges. That knowledge is at the ready, enabling you to concentrate on the more real-time information stream coming your way, such as the dynamics of player behavior and game flow, stack-to-pot ratios, and what kind of hands your opponents have been showing down.

Or take this example from “The Beryl Coronet,” a story in which Holmes supplies a notion that is clearly relevant to the poker player:

“It is an old maxim of mine that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

You may have read of legendary calls and lay-downs, like Brunson’s call of a big river bet with jack-high back in the early days of Texas hold’em. And you quite rightly wonder: How did he do that? But when he logically explains what his opponent must have had, Brunson’s decision seems intuitively obvious.

If Holmes were talking poker here when he talks about eliminating the impossible, he might say, “He can’t have an overpair or a set, and if he had a big draw, he didn’t get there. Therefore, he must be bluffing, so I call.”

Nowadays we speak less of “putting him on a hand” and more about ranges (which surely is the right approach), but if you can apply Holmes’s ruthless logic, you’ll surely be able to make more confident reads on your opponents in more situations.

Finally, consider the Holmes description of his nemesis Moriarty, the “Napoleon of crime,” in “The Final Problem”:

“He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless like a spider in the center of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations and he knows well every quiver of each of them.”

The person Holmes is describing, dear reader, is your most fearsome opponent. Play him carefully… or avoid his web entirely. After all, game selection is an element of success.

I think you’ll agree that Sherlock Holmes has much to offer the thinking poker player, though I’m not suggesting you give up on Dan Harrington or David Sklansky or Ed Miller or any of the really great thinkers and writers who have devoted themselves to poker.

But knowledge comes in strange packages at times — and Sherlock Holmes’s approach to logic, observation, and deduction can be extremely valuable to poker players. And the stories about him are a helluva lot of fun to read for their own sake.

For more on the thought processes of Sherlock Holmes, check out the excellent Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova. Meanwhile, the Holmes stories are widely available in the public domain — you can download them for free!

Illustrations of Sherlock Holmes by Sidney Paget (1860-1908), public domain.

Get all the latest PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!