Blackjack to Bibles: A Texas Seminary’s Tale of Casino Past

Midnight in Arlington, Texas, August 1947. It’s hot and humid -- even at this late hour. Legendary Texas Ranger M.T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas and three other Rangers quietly slither several hundred yards on their stomachs through woods, grass, weeds, brush, and insects. Any sound or noticeable movement might give away their position to nearby guards, quickly foiling their chance to raid one of the country’s biggest casinos -- the Top O’ the Hill Terrace.

The elaborate gambling house wouldn’t be an easy target. Security at the casino, which hosted some of the biggest names in Hollywood, sports, and entertainment, was amazingly tight. Two guards were positioned at the iron gate that guarded a 900-foot drive up to the casino, at the top of a hill overlooking rural Arlington countryside. Lookouts, often armed with rifles, surrounded the house. A buzzer allowed guards to warn the casino of pesky law enforcement.

The house was designed so that casino equipment could be hidden from view via wall panels and hidden in underground tunnels within a few seconds. A hidden tunnel led gamblers 30 yards into nearby woods, where they could easily walk to the nearby tea garden. Half-eaten sandwiches and glasses of wine would be positioned at tables for guests, as if it were all just a gathering for a night under the stars.

As Gonzaullas and his men slowly crawled, two men guarded steel doors to the basement. Surely sweat-soaked and tired, the Rangers waited for an opportunity near the rear door. After several attempted raids, all proving fruitless in shutting down the Top O’ the Hill, the Rangers sought to catch the casino in action and close it down for good.

Soon a guest attempted to enter and the lawmen sprung into action. Three Rangers burst toward the door and entered. They kicked in two more wooden and glass doors before making their way into the casino -- the action running in full view with 50 players and eight dealers. A Ranger in the underground tunnel caught several gamblers attempting to flee. Lone Wolf and his men destroyed craps and blackjack tables, slot machines and roulette wheels, an estimated $25,000 worth of equipment.

While the casino stayed open a few years even after the raid, its best days were behind it and the raid signaled the Metroplex’s new stance on “wide-open” gambling of the ‘30s and ‘40s. Gonzaullas told the Dallas Morning News: “This raid is to serve notice on this place and any other in this area that they are going to be stopped if we have to call on them every night. This is not part of a campaign to make a few raids and then let the heat off. From now on we raid for keeps. This place and all the others are going to stay closed.”

Tea room to backroom

Opened in the 1920s, the Top O’ the Hill Terrace had quaint beginnings. Beulah Marshall bought land and built a tearoom along the Bankhead Highway in the early 1920s. Dinners featured fried chicken cooked over a wood-burning stove, and bridge was played after afternoon luncheons. From the tea garden, with thick sandstone walls, fish pond, and fountain, customers sat and enjoyed the picturesque view of the Tarrant County countryside.

When the 46-acre property went up for sale, Fred Browning and his wife purchased it in 1926. After running a plumbing business, Browning had a different career in mind — casino boss.

“When he moved in, he had gambling in mind,” says Vickie Bryant, head of Arlington Baptist College’s Heritage Collection and historical tour guide at the college. The college is located on the former grounds of the casino, not too far from AT&T Stadium, home of the Dallas Cowboys.

Browning began hosting casino games at his home at the top of the 1,000-foot Arlington hill. He had bigger plans for the estate, however, and construction began soon after he purchased the property. The tearoom itself was moved from its foundation, and construction began on the real heart of his venture -- a basement twice the size of the house itself. Tunnels were built, along with secret passageways and panels for storing casino equipment during a raid. After construction, the tearoom was moved back to its original location, and the Top O’ the Hill casino was soon open for business.

The casino boss spared no expense in making his casino, restaurant, and brothel top of the line. Gamblers enjoyed exquisite meals on fine china and high-end liquor from the elegant bar. All meals and drinks were free -- a forerunner to Las Vegas freebies. The effort paid off, attracting celebrities and high-rollers from across the country. After dinner, the night’s guests were escorted to the basement, where a full-scale casino awaited their action. On weekends, the gambling continued until daybreak.

Browning’s security measures assured patrons of privacy and kept out prying eyes of the law. Another security measure was a floor above the casino, unknown to gamblers. Here the casino’s security staff could monitor the action on the casino floor and possible cheating by gamblers and dealers alike -- a precursor to the modern casino’s “eye in the sky” system of cameras.

“It was very high-tech for back then,” Bryant says of the casino. “By the time the police and Texas Rangers got in, it would be converted into a dining hall. And all that would be left were employees and they’d be sitting around singing hymns.”

Business booms, raids follow

Business boomed in the ‘30s and ‘40s at the Top O’ the Hill. An average night saw 50-100 finely dressed guests at the blackjack, craps, roulette, poker, and slot games, with action in high gear. A quarter-million dollars could change hands in a night. Tuxedo-clad dealers were known to keep their nails polished for a more refined presentation. Area bootleggers kept the place supplied with booze before Prohibition’s repeal in 1933. Celebrities flocked to the nightly action.

“You didn’t get through the front gates unless you were famous, infamous, had a lot of money, or were an invited guest,” Bryant says.

Hollywood gamblers at the place were numerous and included Clark Gable, John Wayne, Lana Turner, Gene Autry, Will Rogers, Frank Sinatra, and many more. Wealthy men like H.L. Hunt dined and gambled at the casino. Infamous guests included Jack Ruby and Bonnie and Clyde Barrow. Browning, who also managed boxers, had so many boxers gambling and staying on the property that an Olympic-size swimming pool and sparring ring were installed onsite. Jack Dempsey, Max Baer, Joe Louis, Lou Brouillard, and Lew Jenkins trained and gambled at the Top O’ the Hill.

The casino may have left an even larger impression on the gambling world. Gangster Bugsy Siegel gambled there and is believed to have modeled his Flamingo Hotel and Casino after the amenities at the Top O’ the Hill. While Siegel was gunned down in 1947, the Flamingo set the stage for the modern Las Vegas.

Rolling craps

Raids at the casino throughout the ‘30s mostly proved useless. Officers would find no gambling equipment or if they did, it would be sitting unused thanks to Browning’s security. Equipment might be occasionally confiscated or destroyed, but the gambling would eventually go on. Other times, witnesses wouldn’t testify, or charges would be dropped or reduced to a fine.

But gambling in Tarrant County had an unrelenting enemy in J. Frank Norris, a fiery Baptist preacher who founded Fundamental Baptist Bible Institute in 1939 in Fort Worth, which became Bible Baptist Seminary in 1945. Norris opposed “wide open” gambling and supported Prohibition. He spearheaded efforts to close Top O’ the Hill, even testifying before a grand jury and helping with a raid in the 1930s.

"By 1946 Benny Binion had become the power behind the Top O’ the Hill."

“It is a high society gambling place – that’s the place you need to raid,” he told a grand jury.

For his efforts, Norris’s home and church were burned down twice. Undeterred, he vowed that he would purchase the property when the Top O’ the Hill was shut down.

After World War II, Browning experienced financial trouble. A horse racing enthusiast, he owned horses that raced at Arlington Downs with Red Pollard, the famed rider of Seabiscuit, even occasionally serving as his jockey. But his horse racing ventures proved unsuccessful. As his debts mounted, a well-known Dallas gambler, gangster, and casino legend began bailing him out.

“Whether this was a favor to Browning, a business arrangement, or a hostile takeover is unknown, but by 1946 Benny Binion had become the power behind the Top O’ the Hill,” writes Gary Sleeper in I’ll Do My Own Damn Killin’, his definitive book on the Dallas gambling wars and Benny Binion. While living in Las Vegas, much of the casino’s profits went to Binion’s empire. The cowboy ran Dallas casinos and numbers rackets throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s.

After Gonzaullas’s raid in 1947, the tide had turned against the Top O’ the Hill — and Metroplex gambling joints. Law enforcement continued to crackdown. Stars stopped showing up at the Top O’ the Hill and Vegas offered legalized casinos, making a night of gambling an easier affair. The casino remained open a few more years before becoming the Arlington Club. Browning got the property back in 1953, but died the same year.

Poker to preachers

Norris’s prediction came true in 1956 when his Bible Baptist Seminary bought the property for $150,000. The former casino now housed seminary students -- certainly a reversal of fortune.

Under the direction of seminary leader, Earl Oldham, any remaining gambling equipment was destroyed. Renamed Arlington Baptist College in 1972, just a few relics of the seminary’s “seedier” past remain. Some poker chips are kept in the college’s museum as well as a prostitute’s cape once worn by Oldham's wife in church. Pictures of Browning and his racehorses and tack equipment from his stables are also on display.

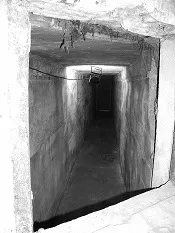

After years of concealing its casino past, the college on West Division has embraced it, offering tours of what remains of the Top O’ the Hill. The tearoom house is now the college’s administration building and the casino is the church’s kitchen. At the back of the kitchen lies the three-foot wide escape tunnel, lit by a single bulb. Outside, the tunnel’s exit peaks out the hillside, homes now covering the countryside below. Escaping gamblers would quickly scamper up a retaining wall and a series of steps to the awaiting tea garden.

The swimming pool and tea garden also remain, and much of the college remains the same including the sandstone wall, wrought-iron fence, and guard towers. The college believes showing its past helps spotlight its true mission, training tomorrow’s Christian leaders, pastors, and missionaries.

“We’ve been tight-lipped (in the past),” Bryant says. “We feel like we can tell the story now. We’ve gotten millions of dollars of free media coverage. I always like to tell how a Bible college can tell the story of a casino. Our story is how we’ve taken the place from poker to preachers.

“Only God could use a casino to put a Bible college on the map.”