Poker & Pop Culture: 'Freeway City' Helps Share Story of Gardena Poker

Just as poker is only part of the story of the 1974 film California Split — about which we were recently reminiscing with writer/co-producer Joseph Walsh — so, too, is poker a small but meaningful part of a larger tale told by the 2015 documentary Freeway City.

The Robert Altman-directed Split is a realistic study of gambling, generally speaking, with poker a favored game of the protagonists. Meanwhile Freeway City presents the story of a Los Angeles suburb where the game of poker had a significant impact on its growth and culture.

Shot, edited and directed over the course of nearly a decade by filmmaker Max Votolato, Freeway City relates the complicated history of Gardena, California. That means going all of the way back to the area's late-19th century agricultural origins, carrying us through its incorporation as a city in 1930 and subsequent response to World War II and its effect on the city's significant Japanese-American population, then moving ahead through the later decades' racial tensions (including the nearby Watts riots in 1965 and their aftermath), political battles, economic challenges and the city's ever-evolving demographics.

Along the way, Gardena's somewhat improbably emerges as a self-proclaimed "Poker Capital of the World" for a significant period of time, a designation rightly earned thanks to the unique concentration of popular card clubs there. These were the clubs whose players David Hayano studied in his book Poker Faces. They were also the ones upon which the "California Club" in California Split was based. For those who are curious, Freeway City offers additional insight into the clubs' origins and history.

A Legal Loophole Creates an Industry

It all started with a bold bet by businessman Ernest "Ernie" Primm, one made possible by more than a half-century worth of ambiguity from California lawmakers and judges regarding poker and its legality.

A prohibition in the state's constitution against many different kinds of gambling in 1879 didn't include draw poker from the list of forbidden games, then further legislation in 1891 again outlawed gambling without including draw. That led to a 1911 opinion specifically describing draw poker — and not (for instance) stud — as a "game of science," thereby keeping draw poker games going in the state over the next couple of decades.

There were cardrooms, too, although not all were licensed and there would be occasional busts depending on the whims of local authorities. Primm was one who in the late 1930s opened a cardroom in Gardena — the Embassy Palace — where draw poker was the featured game.

A raid on the room led to a courtroom showdown, with the judge ultimately following the 1911 ruling and exempting draw poker as a skill game, thereby allowing the clubs to operate as long as the community was in favor of their doing so, as was the case in Gardena.

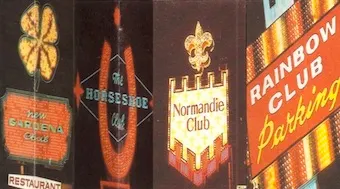

Primm was able to continue operating his club, then opened a second. Before long a half-dozen cardrooms were open in Gardena — the Embassy (later the El Dorado), Monterey, Rainbow, Normandie, Gardena and Horseshoe.

The City That Poker Built

Gardena historian Tom Parks worked for several of the cardrooms and appears in the film to help explain their story. He tells how Gardena was the only city in the county to have cardrooms, which for a time had the effect of limiting other kinds of growth since some restaurants and businesses wouldn't come to Gardena because of the clubs.

Blaine Nicholson, a retired ad man who did public relations for Primm, explains how his former boss had envisioned the Gardena clubs as communal gathering spots where enthusiasts of poker could come together.

"You could come there and play poker among friends, and every hour a chip girl would show up and would collect money from everyone that was there," says Nicholson. As seen in California Split, players would deal themselves, adding further to the feeling of the games being more directly managed by the participants.

Former club employees go on to describe how a light would come on each half-hour to signal that everyone in a seat needed to pay the required fee to continue playing. Some would try to anticipate the light, getting up out of their chairs just before it came on in order to try to avoid paying the fee, but floor people stepped in to make sure they paid their fair share.

The dense collection of cardrooms — and, for a time, relative paucity of other types of businesses — transformed Gardena into a kind of "gambling town," seen from the outside as a kind a mini-version of Las Vegas, although in truth the scene was quite modest by comparison.

Like a Garden, Poker Keeps Growing

During the 1950s the clubs "were full just about every day and every night," explains Parks. Outside of Las Vegas, Gardena became a poker destination for many, with the game and its strategies developing significantly by those who played there.

Parks goes on to relate how Primm, then owner of the already-thriving Monterey and Rainbow clubs, had designs on opening a third cardroom called the Starlight, with the other clubs' owners opposed out of concern Primm was on his way to establishing a monopoly.

The disagreement went so far, the other owners even lobbied in favor of legislation to close all the clubs. The dispute even turned violent with a bombing at the Rainbow — thankfully on a night the club was closed — after which Primm backed off of his plan to build the Starlight.

The film provides further background on other political and business machinations required for the clubs to stay open with support of the community and of those in power.

Advertising on tables helped inform patrons which candidates to vote for — i.e., the "pro-cardroom" ones. So, too, would the cardrooms engage in various other PR efforts, including publishing a magazine about Gardena and giving out coupons for children to go to Disneyland, all of which helped ensure the cardrooms — very deliberately called "clubs" and not "casinos" — would retain the community's support and thus be allowed to continue to operate.

The Decline

The year 1980 marked a turning point in the story of both Gardena's special place in poker's story and the subsequent history of poker in California.

That's when the city of Bell, also in Los Angeles County, voted to permit legalized poker with the California Bell card room opening soon thereafter. More clubs followed, then in 1987 both stud and "flop" games like Texas hold'em and Omaha were made legal in both Los Angeles and Santa Cruz counties, igniting a virtual poker "boom" that eventually spread throughout the state.

"That's when it started really hurting Gardena," says Parks. "They allowed liquor, they allowed high-limit games, and Gardena was still stuck" in a earlier era. "They changed the law and the ordinances later, but it was too late — the customers had already left."

Meanwhile 1980 was also the year the Monterey Club shut its doors, with owner Primm passing away the following year. There were more Gardena card room closings, with only the Normandie lingering on to represent the original "Gardena six."

Freeway City carries the story forward to the present, including talking to the publisher Larry Flynt who in 2000 opened his Hustler Casino on the site of the old El Dorado after purchasing the property in bankruptcy court. (Indeed, the Hustler Casino would quickly develop its own history during its early years as the site of the highest-stakes stud games around featuring many of the game's most famous players.)

Flynt describes "old" Gardena accurately as having been "primarily card clubs" — that is to say, distinct from the spectacle offered by Sin City a few hours east.

"They did not have much pizzazz to them," says Flynt. "I wanted to create the decor that gamblers were used to seeing when they came to Las Vegas."

Such a sentiment echoes how David Spanier described Gardena poker in his 1977 book Total Poker.

The city itself, writes Spanier, "is nothing more than a desolate crossroads between the looping circuit of expressways" — a description that gives an idea of the origin of the "Freeway City" nickname. Given how Gardena then was "a place built up on, indeed, dedicated to, the playing of poker," Spanier finds the games circa mid-1970s as "total lacking in atmosphere," with the play too "mechanical" for his tastes, inspiring in him a longing to escape back to more exciting Vegas.

Dick Miles offers a similar impression in his 1967 Sports Illustrated article "Lowball in a Time Capsule" — discussed previously here. Miles describes the games and players as existing in a "world of their own, isolated from outside life and its problems," and how it seems to him as though “in some prehistoric age they had been quick-frozen and tucked into a time capsule until, thawed by the California sun, they resumed their play heedless of the interruption.”

In other words, even at the height of the Gardena games' popularity, there was something already out-of-step or strangely anachronistic about them — something "stuck" in an earlier era — that perhaps makes the games' later decline less surprising.

Since Freeway City was produced, the owners of the Normandie became embroiled in scandal over violating anti-money laundering laws, having their gaming licenses revoked and being forced to sell. Flynt again was the purchaser, renaming the property the Larry Flynt's Lucky Lady Casino and currently pursuing plans to renovate it further.

All of which removes us even further from Gardena's heyday as a true "poker capital," although it can still be experienced second-hand via resources like Hayano's Poker Faces, California Split and Freeway City,

Freeway City can be viewed online for free via the film's website. And for more background on the film, check out this PokerNews interview with filmmaker Max Votolato.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.