Poker & Pop Culture: Card-Playing Characters in Early Poker Clubs

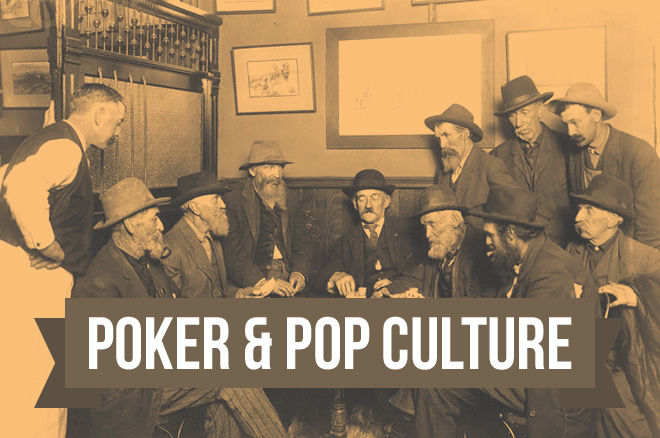

Moving through poker's first century, we've encountered the game being played in saloons, on steamboats, in gaming dens, and in military encampments. Many cultural representations of poker as it was played in the 1800s — both contemporary and those produced later on — highlight those settings for poker as well, as shown in various stories (true and fictional), in paintings, and (later on) in films.

Another popular context for poker that emerged during the latter decades of the 19th century and continuing into the 20th was the private club or salon. As different states established a variety of legal prohibitions and/or restrictions on the game, such clubs became popular among those wanting to find a regular game among known parties where the risk of being cheated, physically harmed, or subject to being raided and shut down was reduced (if not entirely removed).

Poker clubs were also inviting to those who would liked to have played at home but for whatever reason — say, a disapproving spouse — could not.

In fact, a favored literary form inspired by these clubs would emerge late in the century, one echoing a tradition of coffee-house reporting made famous during the earlier age of satire — the "club report."

A Glimpse Inside a Hidden World

Poker clubs have always been a great generator of characters and stories, both back in the 19th century and still today. You might have noticed just last week there appeared in The New York Post yet another peek "Inside the seedy world of underground NY poker clubs."

The feature shared anecdotes from several New York clubs including the ones that helped inspire the 1998 film Rounders. Among those covered, of course, was the famous Mayfair Club frequented by Dan Harrington, Erik Seidel, Mickey Appleman, Stu Ungar, and many other poker players whose fame would extend well beyond the Empire state.

Perhaps the best of the early "club reports" emanated from the same part of the country — David A. Curtis's 1899 collection Queer Luck that shares stories of New York poker games played in "one of those up-town club-rooms that are so quietly kept as to be entirely unknown to the police and general public."

The 13 stories were originally published in The New York Sun, one of three big NYC newspapers during the late 19th century along with the Times and Herald. Most are presented as though told to Curtis by an unnamed "gray-haired young-looking man" with knowledge of the games.

Not all of the stories in Queer Luck are about the New York club, but rather concern other games the storyteller either experienced or heard about elsewhere. In one story titled "For a Senate Seat," he shares an anecdote of "a United States Senate seat lost on four queens." Set just after the Civil War in Minnesota, the story tells of the primary financial backers for two senatorial candidates playing a high-stakes game of five-card draw, with a showdown of four kings versus four queens essentially ensuring the election of one candidate over the other. Another story tells of lawmakers in Washington playing poker, with the outcome of another poker game influencing the passage of a particular bill.

Most of the stories, though, concern characters who frequent the uptown club in NYC, ultimately providing the reader a taste of what the games might have been like. That is to say, not unlike the recent New York Post feature, one gets the sense of having obtained a peek "inside" a closed world known only to those who inhabit it.

Big Hands, Big Stakes

One of the better tales is the one that kicks off the book, titled "Why He Quit the Game." The story focuses on a wild session of five-card draw jacks-or-better in the club involving five players, all of whom are referred to generically by their professions — the Editor, the Congressman, the Colonel, the Doctor, and the Lawyer.

The game usually featured a one-dollar ante, but thanks in part to a series of remarkable hands and big pots the stakes on this night had gradually been increased tenfold.

Indeed, a lot of "queer luck" had marked the session. "Fours had been shown several times... and beaten once," we're told. "Straight flushes had twice won important money," too, and players were routinely being dealt "pat fulls and flushes."

For a while no one remarked on the oddity of so many big hands routinely turning up at showdowns.

"It was as if each man feared to break the run by mentioning it," Curtis explains. At last one player does make a reference to what has been happening, jokingly noting that "the devil himself has been playing with his picture books to-night," and the others agree.

The Congressman then deals a hand, announcing the ante would be doubled to $20 for this one. The Lawyer is dealt a four-flush with two tens, the Doctor gets a pat king-high straight, the Congressman has a pair of queens, the Editor has three deuces, and the Colonel has at least two aces (he doesn't look at his other three cards).

The Doctor opens for twenty, everyone calls, then comes the draw. Again the Doctor leads with a bet of $20, though considering all of the big hands that have been shown during the session he doesn't feel very confident his straight is going to be best. The Editor doesn't improve on his three deuces, and sharing the same lack of confidence folds to the Doctor's small bet.

Both players were correct to be timid, as we learn the Congressman has improbably drawn three sixes to match his pair of queens (his drawing 6x6x6x again evoking the idea that the devil might well be involved). He raises to $40, then the Colonel — who when looking at his remaining cards had found a third ace before he drew — reraises to $90.

The Lawyer, who had decided to pitch one of his tens and keep Q♥10♥9♥8♥, calls the reraise, and at that point the uncertain Doctor folds his straight. The Congressman then makes it $140 with his full house, after which the Colonel pushes it up a hundred more. Then the Lawyer reraises a hundred on top of that. The Congressman just calls, but when the other two continue to add more to the pot he finally folds his sixes full of queens, giving up the more than $300 he's contributed to the pot.

The reraises continue unabated, with the Lawyer eventually going into his pocketbook to pull out a stack of hundred dollar bills to add to the pot. Ultimately the pot has been built up to more than $5,000 when the Lawyer finds himself facing yet another reraise from the Colonel for $1,000 more.

The Lawyer is about to reraise again when he suddenly stops himself.

"The bills were still in his grasp," writes Curtis, "and, instead of laying them down, he sat for a moment rigid as a statue, while his face grew white."

Thinking of various poker stories in fiction, one might assume the Lawyer might be about to drop dead of a heart attack here. But this apparently true story goes in a different direction.

The Lawyer's Crime

The Lawyer rechecks his cards — which baffles the others — then merely calls the Colonel's last raise. The Colonel turns over four aces, but the Lawyer had drawn the J♥ to make a winning straight flush. He rakes the huge pot, though everyone remains tense, still feeling as though "some strange climax was coming, and none could even guess what it could be."

Indeed, there is more to come here. The Lawyer counts up his winnings, then surprisingly hands $2,000 of it back to the Colonel. Then he delivers a speech.

"I am done with poker," he begins, going on to explain that while he loves the game — "To my mind there is no other sport that equals it" — he recognizes that he "stepped across the borderline of dishonor" when playing the previous hand. And having done so, he now thinks the only appropriate response for him is to quit playing poker.

What was his transgression? Did he cheat? No. He had put money into the pot that was not his, but rather belonged to a client. "If I had lost," he explains, "I could not immediately have replaced it."

In the excitement of the hand he'd lost track of what money was his and what was not, and so had mistakenly used some of his client's money that he had been carrying to continue. The amount he gave back to the Colonel corresponded to the amount the Lawyer had won with money that wasn't his.

The Lawyer then asks the others if they believe he owes them as well. They recognize the Lawyer's integrity, and noting how they were friends (having played the game regularly for over a year), agree that he owes them nothing.

The story ends with the Colonel extending his hand to the Lawyer, who "grasped it nervously. One after another, the three others shook hands with him also, and the game was over."

Play for Yourself, But Honor the Club

"Why He Quit the Game" establishes a theme of sorts that runs throughout Queer Luck, namely the "honor" that marks the club games and how those who play in them share a kind of obligation to play square with one another. That is to say, not only should they not cheat, but they shouldn't be less than up front about other aspects of their lives and who they represent themselves to be, either.

The idea runs all of the way through the final story, titled "The Club's Last Game," in which a couple of regulars in an otherwise friendly, low-stakes weekly game end up revealing themselves to be "professionals" (in a way), with their lack of honesty with the others ending up causing the game to be discontinued.

The "club" represents a kind of refuge in these stories, a place where poker players can go when there aren't available alternatives for their card playing. As the gray-haired young-looking man says in the last story, the club well serves poker players who find themselves in places "where you have to keep very quiet about your card playing unless you don't give a rap for your standing in the business community, to say nothing of your social position."

But in order for the club to be a true sanctuary, there has to be a commitment from the individuals to look after the interests of the entire group. It's like any poker game — everyone who plays wants to win, but everyone also has to work together, too, for a game to occur at all.

We'll survey a few other literary-leaning poker clubs of the era next week, and after that look at one of the earliest poker films ever made that also highlights the poker club as a newly popular setting for the game.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Be sure to complete your PokerNews experience by checking out an overview of our mobile and tablet apps here. Stay on top of the poker world from your phone with our mobile iOS and Android app, or fire up our iPad app on your tablet. You can also update your own chip counts from poker tournaments around the world with MyStack on both Android and iOS.