Poker & Pop Culture: Professional Card Sharps Rocking the Boat

"Poker expresses the tension between nature and civilization, between order and lawlessness."

So writes Associate Professor of Humanities Kevin L. Stoehr in a 2006 essay focusing on the role of poker in Western movies, "Civilization and Wilderness: Poker, Hobbes, and Classic Westerns."

In his essay Stoehr highlights several different paradoxes of poker, many of which aren't actually specific to the Old West such as the way luck and skill coexist as factors affecting the game, or the way players employ both logic and intuition when weighing decisions. But the paradox that most intrigues him concerns the way poker — particularly in the handful of Westerns he examines — represents a kind of isolated, curious example of civilization amid the chaos of the Old West.

In these movies, Stoehr notes, "poker plays an important role as a leisurely — though also at times deadly serious — game of chance, one that typically entertains everyday saloon patrons while keeping gunslingers amused when they're not robbing stagecoaches... or shooting up shop windows."

The game stands as a kind of baize-covered island of relative calm, he suggests, amid the wild and often lawless frontier communities and uncharted territories swirling around them. Meanwhile the game itself curiously combines both order and disorder — it's "a communal, typically civilized game with well-defined rules of gamesmanship and sociability" while also "a game that calls upon a certain 'primitive' spirit of survival and individuality in its 'winner-takes-all' environment of competition and greed."

In other words, in the Old West (particularly as depicted in classic Westerns) poker provides a kind of peaceable escape from the unruly and violent turmoil happening outside those swinging saloon doors — at least until someone is caught cheating and the guns come out. At the same time, though, the game also reflects that ongoing "tension" between civilization and wilderness always present during westward expansion — one reason why in many of these films the disputes that arise in the poker scenes neatly parallel larger conflicts being explored in the main plots.

Take a Ride on the River

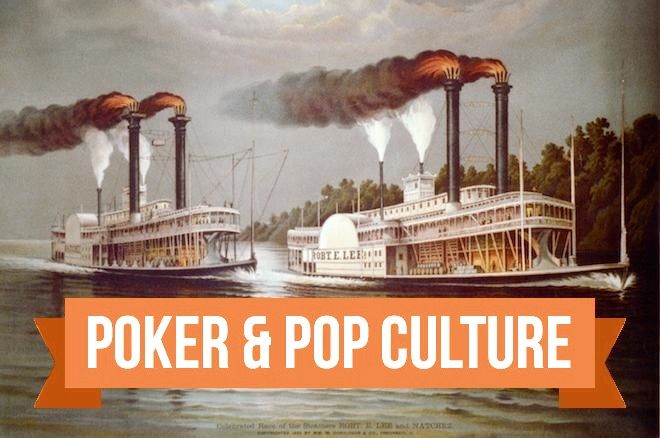

What happens, though, when we leave the frontier towns and their saloon poker games and take trips elsewhere — say, via one of the many steamboats traveling the Mississippi River from Minnesota to New Orleans and back, or along the numerous tributaries extending well into the northeast, or westward throughout the newly-acquired, massive territory gained via the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

In a way, steamboats present a different sort of paradox floating through 19th century America. On the one hand, they were a marvel of human ingenuity, an emblem of industrial advancement that enabled civilization to grow and prosper as never before. But once they left their ports and moved out onto those rolling waters, they also became momentarily detached from the societies they were helping to advance, transforming into discrete worlds of their own not necessarily bound by the order-maintaining rules observed on land.

As we move over from "saloon poker" to "steamboat poker," let's keep in mind Stoehr's suggestion that besides reflecting various poker paradoxes, 19th-century saloon games could be considered as sometimes providing a temporary, civilized alternative to an otherwise unruly, "wild West." Meanwhile, we might consider the contemporaneous traveler boarding a steamboat and eventually finding the card parlor as having stepped into a different kind of wilderness — one full of marked cards, cold decks, hair triggers, and insatiable sharps.

Relative Freedoms Out on the Water

Following some initial late 18th-century trials by others, Robert Fulton's advances helped launch the first successful steamboat run when the Clermont navigated its way through a two-day voyage on the Hudson River in 1807. By the 1810s the first major steamboats began traversing the Mississippi, and within a couple of decades more than 1,200 of them would be put into service.

The steamboats greatly facilitated all kinds of commerce, including enabling farmers to ship crops to markets far and wide in the still primarily agrarian society of the first half of the 1800s. Cities like St. Louis, Memphis, and, of course, New Orleans were among the several important ports, with the hundreds of gaming dens in operating in New Orleans during the century's early decades helping ensure the spread of poker, faro, and other gambling games via the steamboats up and down the Mississippi and throughout the country.

Also of special relevance to poker's progress on these vessels was the more general difficulty of regulating the steamboats' commerce, traffic, manufacture, and operation.

In some respects, the situation was analogous to the sudden growth of the internet in the 1990s and the efforts of legislators to address it via the cumbersome legislative process, with laws still lagging behind in many respects a couple of decades later. Particularly before mid-century, the still-nascent federal government exerted only limited purview over the states, with the country's waterways being even less easy to manage or regulate from a legislative point of view.

It wasn't until 1838 — well into the "golden age" of steamboats — that the Interstate Steamboat Commerce Commission was established to regulate traffic. It took still longer until the federal government was able to pass the Steamboat Act of May 30, 1852 to enforce inspections and other measures in response to a series of fatal accidents.

As you might imagine, such a lack of oversight extended as well to the gambling games that took place among the boats, with poker featuring prominently in the mix. Indeed, some of the earliest poker games ever described took place on steamboats, including Henry Cowell's account of an 1829 game aboard the Helen M'Gregor (discussed previously here).

A category of individuals soon emerged who made their living exclusively via gambling on steamboats, their status becoming generally recognized as a commonly understood (if not accepted) occupation. In his history of gambling Roll the Bones, David G. Schwartz notes that by the mid-1830s "it was estimated that between 1000 and 1500 professionals worked the steamboats that plied the Mississippi and Ohio between New Orleans and Louisville."

For many of these "professionals," the unregulated boats provided freedom from lawmakers' attempts to curb or control games. They also offered an escape from the wrath of others such as the mob in Vicksburg, Mississippi who demonstrated their opposition to gambling by lynching five gamblers in July 1835.

Out on the waters, though, many of the gamblers operated with relatively less restriction. They also formed part of the cast of characters for just about every voyage. As James McManus notes in Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker, "whatever the sharps' moral or social standing, they soon became so much a part of riverboat life that many captains believed it was bad luck to leave port without one aboard."

The appearance of gamblers' names among passenger lists may or may not have ensured the safe completion of a steamboat's scheduled trip. But they sure made those expeditions more interesting, introducing a healthy measure of uncertainty and sometimes even chaos into travelers' journeys.

"The Professor's Yarn"

American humorist Mark Twain chronicled steamboat culture extensively in numerous writings, most notably in a memoir collecting stories from his time as a pilot titled Life on the Mississippi (1883). It's from one of those stories we'll draw our first cultural response to "steamboat poker," a chapter titled "The Professor's Yarn."

Twain himself enjoyed poker, though followed a personal policy to avoid games involving the skilled cheaters like the steamboat sharps. A fellow pilot who once worked with Twain affirmed "Mark wouldn't gamble with them fellers on the boats... [that] were full of gamblers in those days. Mark liked a little game of poker as well as the rest of us, but he was mighty particular who he played with."

Twain's aversion to savvy riverboat gamblers is shared by the narrator of "The Professor's Yarn," a teacher passing along a tale from his former career as a land surveyor.

After accepting a job in California, the Professor embarks on a several-week journey that includes trip by sea up the continent's west coast to his destination. He describes the other passengers generally, then focuses on the "three professional gamblers on board — rough, repulsive fellows." He tries to avoid the trio, but "could not help seeing them with some frequency, for they gambled in an upper-deck stateroom every day and night," and during evening walks he often "had glimpses of them through their door, which stood a little ajar to let out the surplus tobacco smoke and profanity."

"They were an evil and hateful presence," says the Professor. "But I had to put up with it, of course."

The trip becomes more pleasant, though, once the Professor befriends a young cattleman named John Backus. At one point Backus suggests a proposal whereby the Professor, in his capacity as a surveyor, might allot him some free land in exchange for payment, with Backus showing the Professor his stash of a thousand dollars' worth of gold as he does.

The Professor declines that invitation, then is later dismayed when he finds Backus having been recruited by the gamblers to play in their poker game. From all appearances, the gamblers are taking advantage of the naive country boy, plying him with drink as they soberly work to extricate as much money from them as they can. "It was the painfulest night I ever spent," laments the Professor.

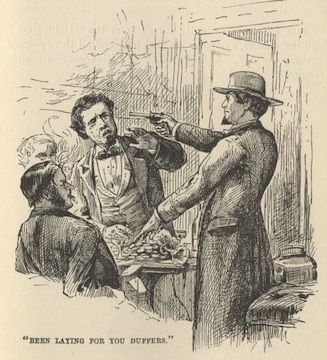

The tale soon reaches a climax in the form of a big hand of draw poker involving Backus and one of the three gamblers named Hank Wiley. After Wiley draws one card and the other players three each, a series of bets leave only Wiley and Backus in the hand and an enormous "gold pyramid" of gold coins in the middle, with one last raise and call bringing the pot to $20,000.

"What have you got?" asks Backus, and his opponent confidently reveals his hand. "Four kings, you d----d fool!" he says. Backus then tables his cards. "Four aces, you ass!" he bellows.

Backus knows, however, the declaration of his hand may not be enough to ensure his collection of the winnings. While "covering his man with a cocked revolver," he delivers an additional statement.

"I'm a professional gambler myself, and I've been laying for you duffers all this voyage!"

What It Means to Be a "Professional"

As it turns out, one of the other three gamblers had joined forces with Backus, thereby ensuring the four-kings-versus-four-aces scenario in the latter's favor. The accomplice had acted as a double-agent of sorts, having previously agreed with Wiley that Backus would be dealt four queens which would make Wiley's quad kings best.

In fact, as the Professor would later find out, Backus had been putting him on as well by posing as a cattleman, establishing a persona that would help him fool the gamblers into thinking he was more rube than rogue.

The story well presents the danger and unpredictability the gamblers introduce into the world of the steamboat (the "evil and hateful presence" abhorred by the Professor). It also neatly encapsulates the figure of the "professional gambler" — as Backus very deliberately calls himself — and how he tended to operate in such a context.

As the stories of other, real-life examples of such "professionals" will attest, the rules of civilized society didn't necessarily apply when it came to steamboat poker. Or, rather, there were other, different rules — often changing and arbitrary — that governed the games, adding considerable unsteadiness to the boats' passage.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Images: "Celebrated race of the steamers Robt. E. Lee and Natchez" (1870), William M. Donaldson, public domain; Life on the Mississippi illustration courtesy Project Gutenberg

Want to stay atop all the latest in the poker world? If so, make sure to get PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!