Poker & Pop Culture: Heads-Up for Pols -- Henry Clay v. Daniel Webster

Similarities between poker and politics are so obvious, it almost seems redundant to remark how one resembles the other. Of course politicians are always working on their images, using aggression, raising the stakes, exploiting edges by applying pressure to opponents, and "going all in" behind this or that cause.

Politicians bluff, too. A lot.

We've already seen multiple articles during the present election cycle assessing presidential candidate Donald Trump's "poker strategy" during his campaign, with Phil Hellmuth even being called upon to comment on the subject. But that kind of analysis tends to come every election, given how poker and politics really are two of a kind.

Many think being proficient at poker can be useful to those hoping to reach the nation's highest office. Those who do echo Albert Upton, a college professor whose most famous student, Richard Nixon, was one of many examples of poker-playing presidents. Upton once told a Nixon biographer he was "convinced that a man who can't hold a hand at a first-class poker table is unfit to be President of the United States," a sentiment with which many agree.

It's true — learning poker can help teach presidential candidates lessons in the ways of negotiation, diplomacy, and even salesmanship. Even so, being known as a card player isn't always a positive on the campaign trail. Barack Obama's background as a poker player (to cite an example) might have helped him among fellow players during his presidential campaigns, though it didn't necessarily enthuse that segment of the voting population who are less comfortable with gambling games.

We look again this week at one of the earliest examples of poker being discussed in print, and this time the story gives us reason to discuss two of the first examples of U.S. presidential candidates who were poker players — two "pols" who famously played poker against each other.

A Common Claim About Clay

In 1844, the stage actor Joe Cowell published a memoir titled Thirty Years Passed Among the Players in England and America that included a mention of poker, another interesting, early cultural response to the still-new game that helps fill in more gaps in the early historical narrative.

Cowell's book further attests to poker's spread up the Mississippi and through the American south thanks to his inclusion of the story of a poker game occurring aboard the Helen M'Gregor back in December 1829. At the time Cowell, an Englishman, was in the middle of a tour of American stages, and having just boarded near Louisville was traveling back down to New Orleans.

An inexperienced card player himself — "my skill only extending to a homely game at whist," he insists — Cowell becomes introduced to several card games that are new to him while aboard the ship. One of the games is "uker" or euchre, and his reference to it represents one of the earliest mentions of that game as well.

Like other early poker stories, Cowell's again takes place during the evening hours, during a "foggy, wretched night" of low visibility for those piloting the ship.

Near the beginning of the episode — before the game switches to poker — a suspicion of cheating results in a player suddenly chopping another's finger off with a Bowie knife as a punishment for the crime. The tension is therefore understandably high once they turn to poker, during which opponents' cards are "carefully concealed from one another" while "old players pack them in their hands, and peep at them as if they were afraid to trust even themselves to look."

The game once more is "Old Poker," which Cowell introduces as "exclusively a high-gambling Western game, founded on brag [and] invented, as it is said, by Henry Clay when a youth."

It's this reference to the politician Clay — and spurious credit to Clay as poker's inventor — that gives us a chance to talk about early presidential candidates playing poker.

"Redoubtable Warriors in Terrific Poker Battles"

The linking of poker with the vying game of Cowell's own country is warranted, as the game of brag most certainly bears some affinity to poker, especially as it was first played. However, Cowell's repetition of the claim that the game was invented by the U.S. senator, former Speaker of the House and former Secretary of State, and frequent presidential candidate is not.

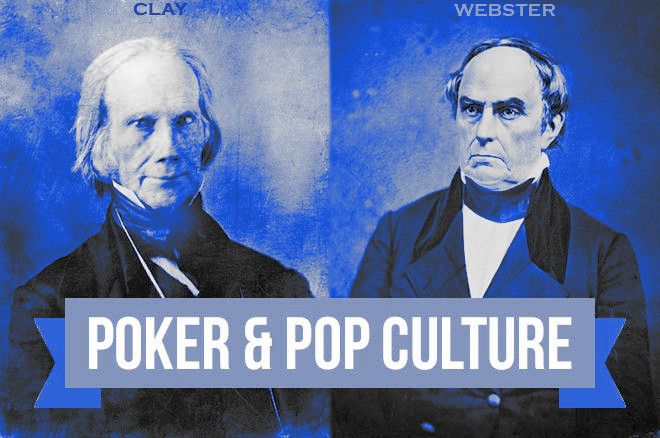

Henry Clay mounted unsuccessful presidential campaigns on five different occasions from the 1820s through the 1840s, including making it to the general election three times. He was known to be an avid (and often successful) poker player, and indeed stands near the beginning of a long list of U.S. political figures for whom poker was a favored pastime. But while the Kentuckian's predilection for poker was clear, many stories about his playing show signs of embellishment.

One of uncertain validity pits Clay versus fellow statesman Daniel Webster of Massachusetts who also served in both houses as well as Secretary of State, and who also ran unsuccessfully for president three times. The much-repeated story finds Clay and Webster raising back and forth during a hand to create a pot worth thousands, concluding with Webster showing down a lowly pair of deuces to beat Clay's ace-high.

In A Game of Draw Poker (1887), John W. Keller rightly questions this and other tales promoting the pair as "redoubtable warriors in terrific Poker battles." Keller notes in particular how the hand concludes with Clay calling with ace-high, and that such a "play would indicate that he was ignorant of Poker." ("Poker players of to-day do not accept this story as true," concludes Keller.)

W.J. Florence in A Gentleman's Guide to Poker (1890) similarly describes the same hand as "contrary to the probabilities... as well as to good play in general."

What is not improbable is the likelihood that accounts of Clay and Webster's "terrific Poker battles" might have been influenced by the great, history-altering debates the pair would have — along with South Carolina's John C. Calhoun, the third member of the "Great Triumvirate" — including their negotiations of compromises concerning slavery and how to treat new territories following the Civil War.

In any case, Florence shares one other fantastic poker story involving Clay that has him drawing a pistol against an opponent he discovered to have unfairly secured an extra ace. Then, after his opponent is sent away, Clay is said to have dramatically fired the weapon into the player's vacated chair. Perhaps Clay was leaving a warning to others — try to hide a bullet up your sleeve, and you'll get another one to go with it.

Whatever the historical veracity of such stories, Clay's reputation as a player was without a doubt common knowledge by the time Cowell published his memoirs. During the presidential election of that same year (1844), supporters of Clay's opponent James K. Polk distributed a pamphlet claiming that Clay "spends his days at the gaming table and nights in a brothel."

John Quincy Adams (who defeated Clay in an earlier presidential election) would similarly record in his memoirs how Clay's "armorial bearings" were then understood as "a pistol, a pack of cards, and a brandy bottle."

In such a political climate, taking one more step to suggest Clay actually invented poker would not have been difficult, but no other evidence exists to corroborate such a claim.

Everybody Has Quads (Again!)

To circle back to the story of Cowell's poker game on the Helen M'Gregor, he explains it was played "with twenty-five cards only, and by four persons," though confusingly adds that only aces, kings, queens, jacks, and tens were used (totaling 20). His poker education appears to have been limited as he comes away from the game a loser, and when the boat accidentally hits a small island, "the hubbub formed a good excuse to our game, which my stupidity had made desirable long before."

Before stopping, though, one final hand is played out involving four others, with bets starting at $10, then $20, then suddenly $500 and $1,500. Three players remain at showdown, with one player's four kings and an ace proving an unbeatable hand, incredibly besting the four queens with an ace held by one opponent and four jacks with an ace of the other.

It appears yet another hard-to-believe hand of Old Poker, although Cowell is able to confirm that "the truth was, the cards had been put up, or stocked, as it is called." Even so, the discovery of cheating does not lead Cowell to censure the game or declare poker an evil to be avoided (like some of his contemporaries do). In fact, his impression of the game and those who play it ends up being much more favorable than that.

"After the actors, there is no class of persons so misrepresented and abused behind their backs as the professional gamblers," writes Cowell, lamenting how "as in my trade, the depraved and dishonourable are selected as the sample of all."

Cowell rather wants to elevate the gamblers whom he encountered repeatedly on steamboats and in hotels, and to insist "they cannot be excelled by any other set of men who make making money their only occupation." He wants us to know gamblers are good people, but also can't resist telling us about digits lost — the cash kind and fingers, too! — while playing (and cheating) at cards.

I suppose we can conclude Clay's poker playing didn't diminish him as a presidential candidate in Cowell's eyes. It might have helped him, even.

What about today? Would it help or hurt a presidential candidate in 2016 to be known as a poker player?

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Want to stay atop all the latest in the poker world? If so, make sure to get PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!