Poker & Pop Culture: The First Hand Report -- Quad Aces v. Quad Kings!

Long before poker came to be, cards and gambling already had achieved considerable notoriety. Just as the first version of the game appearing in the American south in the early 1800s combined elements of other card games, so, too, did poker inherit from those earlier games a kind of outlaw status right from the very start.

Poker was dangerous. Unsafe. Of uncertain legality. A threat to individuals and perhaps society as a whole. At best an idle waste of time and at worst a way to lose whatever you were willing to risk in the game and maybe even more than that.

In fact, by the time we find the earliest reference to poker in print — a first reflection on the game by the culture — we discover many of the hallmarks of poker's dark, dangerous character turning up in this very first poker story.

Poker News from the Frontier

In the spring of 1833, Congress created a new military organization called the United States Regiment of Dragoons. Its duties included exploring the Mississippi Valley to seek treaties with Native American tribes while also defending the already established frontier.

Over that summer officers were recruited to serve from every state in the Union, all 24 of them. By year's end five companies' worth of men belonging to what would subsequently be called the "First Regiment of Dragoons" were sent to Fort Gibson in the Arkansas Territory, with five more companies joining them the following spring.

Accounts of the First Regiment's campaigns started appearing shortly after they were conducted, including an official one kept in journal form by Lieutenant T.B. Wheelock. In 1836 a lively telling of the First Regiment of Dragoons' story was produced with title Dragoon Campaigns to the Rocky Mountains; Being a History of the Enlistment, Organization, and First Campaigns of the Regiment of United States Dragoons; Together With Incidents of a Soldier's Life, and Sketches of Scenery and Indian Character.

Published by New York City booksellers Wiley & Long, the book presents a series of letters written anonymously "BY A DRAGOON" from August 1833 to the fall of 1834. They contain a full and occasionally critical picture of the regiment's organization and operation during this period.

Drawing largely from his own experience, the author of the Dragoon Campaigns supports his narrative with additional material from his various correspondents, from Lt. Wheelock's journal, and from others' accounts. The letter-writer describes himself as hailing from western New York, one of a few clues along with his age that have led some to identify a young soldier named James Hildreth as the author.

Some have disputed such attribution thanks in part to the book's inclusion of material describing later campaigns in which Hildreth himself did not take part. They think another, older veteran of the campaigns originally from England named William L. Gordon-Miller is the true author, with Hildreth perhaps having merely been only involved in the book's sale to Wiley & Long.

In any event, among the letters appearing in Dragoon Campaigns to the Rocky Mountains is one written from Fort Gibson during the spring of 1834 relating "an occurrence" thought by the author to provide "a little amusing material."

It's a minor episode in the context of the account, but an important one for the history of poker.

A Big Hand, and a Major Blow-Up

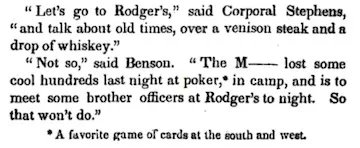

The story begins with a small group of officers discussing plans to enjoy a final evening before decamping once more. One suggests they eat dinner at the dwelling of an affluent Cherokee named "old Rodger" located a short walk across the prairie. However, another member of the group quickly objects, noting how "The M---- lost some cool hundreds at poker last night, in camp, and is to meet some brother officers at Rodger's to night."

The "M----" is the Major, we're made to assume. (We also might assume the Major is a bit of a pill after losing at cards.) However with the mention of "poker" the author isn't so sure the reader follows what he's referring to, and so a helpful footnote is added clarifying that "poker" is "A favorite game of cards at the south and west."

The officers decide to elect just one among the group to sneak away from camp to old Rodger's in order to secure a quart of whiskey to help enliven their evening. After losing a "toss up," the teller of the story is the one picked to go.

"The business I had in hand was one of double risk and severe penalty," he explains, noting how not only was alcohol forbidden, but being caught away from the barracks without a pass was strictly prohibited as well. On arriving at Rodger's, he first listens through a window and hears both the Major and Captain engaged in an animated discussion.

Soon he realizes what is going on — his superiors are once more playing that "favorite game" of the region.

Although not specified, the most likely variant being dealt in game was what would later commonly be referred to as "Old Poker." Like the French game poque that first surfaces during the 16th century, Old Poker employed just 20 cards — the aces, kings, queens, jacks, and tens — with five dealt to each player, no discards or draws, and only a single round of betting. Suits were of no consequence, with only high card, one pair, two pair, "triplets" (three of a kind), "full" (full house), and four of a kind being recognized hands, and neither straights nor flushes were considered.

"'I'll stake you another ten,'" he reports hearing the Major say, and soon we realize he's arrived in the middle of a hand. "'Done,'" replies the Captain, a response that appears to indicate another raise.

The Major continues to up the stakes to "twenty," "fifty," then "another hundred." None of these bets causes the Captain any consternation as he steadfastly remains in the hand, raising back each time.

At last the Major stops raising, "and throwing down his cards exclaimed, 'There's four kings! What have you got?'"

"'Only four aces!'" responds the Captain who then gathers his winnings.

An incensed Major curses, "at the same time splitting the pine table with a blow of his fist." That's right — in this, the first reference to poker in print, a losing player has a tantrum and smashes apart the furniture.

Talk about a table break.

"We shall probably have an hour's extra drill in the morning," grimly reflects the author, who after successfully purchasing the desired whiskey from one of Rodger's slaves escapes to reunite with his fellow officers for a night of drinking and storytelling behind the bayou.

Deals in the Dead of Night

This first hand report includes several details that would be repeated frequently in subsequent poker tales, some to the point of becoming clichés.

The nighttime setting, with the air of illicitness thickened further by the author's surreptitious run for contraband, introduces poker as a game played in the shadows, hardly sanctioned by the law and/or what was typically permitted there at Fort Gibson. It's necessarily a private, secret game, not something the fellow by the window was supposed to witness at all.

The hand then features multiple raises concluding with a dramatic showdown, resembling a verbal battle ending in violence. That also prefigures future stories of poker hands (especially those from the Old West), with the Major's breaking of the table afterwards illustrating an oft-traveled short step from intellectual intrigue to physical frustration.

The mathematically improbable outcome of four aces beating four kings will likewise emerge as a commonly evoked concluding twist punctuating numerous poker stories going forward, too.

In Sol Smith's Theatrical Management in the West and South for Thirty Years (1868), he describes a hand he played aboard a steamboat just a year after the Dragoons story takes place in which he won a large pot off of a "blackleg" with four aces over the latter's four kings. Only later does Smith discover he won the hand after his opponent's accomplice fixed the deck to deal out the aces and kings, but mistakenly swapped the hands.

Nearly a half-century after those hands were played, Mark Twain would repeat the conceit in his 1883 short story, "The Professor's Yarn." One of the first films ever to depict poker, D.W. Griffith's anti-gambling short The Last Deal (1910), would feature a hand in which four aces beat four kings. And a little after that W.C. Fields would show down four aces to beat four kings — and four queens and four jacks! — aboard a train in Tillie and Gus (1933).

The Dragoon Campaigns author refrains from casting any judgments about the prudence of gambling at cards — not directly, anyway. Neither does the storyteller hint that anything untoward might have happened in the hand between the Major and the Captain, although cheating does seem a clear possibility.

But remember — our young dragoon is just an eavesdropper, happening on a game he himself doesn't play and perhaps doesn't entirely understand. If cheating were occurring, would he even recognize it?

His account does imply an understanding of one thing about poker, however.

To his way of thinking, taking on the "double risk" of getting caught on a forbidden booze run is much more favorable than betting hundreds on a hand of this "favorite game of cards at the south and west."

That game is trouble!

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Want to stay atop all the latest in the poker world? If so, make sure to get PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!