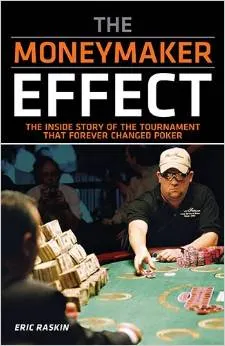

PokerNews Book Review: The Moneymaker Effect by Eric Raskin

There are few game-changing moments in poker that rival the 2003 World Series of Poker. Chris Moneymaker’s improbable win changed poker forever, and now poker fans can not only relive that special tournament, but experience it in a different light in Eric Raskin’s book The Moneymaker Effect: The Inside Story of the Tournament That Forever Changed Poker.

The book, which was expanded from the Grantland.com feature When We Held Kings, is written primarily in “oral history” format, with more than 30 people who were involved in the 2003 WSOP telling the story. In addition to Moneymaker, Raskin talked to players such as Phil Ivey, Phil Hellmuth, Howard Lederer, Dan Harrington, and Barry Greenstein, as well as world-renowned tournament director Matt Savage and various members of the 441 Productions team.

I’m a fan of poker history, but I had reservations on The Moneymaker Effect. After all, wasn't the 2003 WSOP a beaten horse? Well, as it turned out nothing could have been further from the truth. From start to finish, The Moneymaker Effect delivered and was chalk full of new information and engaging perspectives. For instance, we all remember Moneymaker's “bluff of the century” against Sammy Farha from endless ESPN broadcasts, but Raskin gives readers something the cameras couldn’t catch — a glimpse inside the players’ heads.

To read an excerpt from The Moneymaker Effect: The Inside Story of the Tournament That Forever Changed Poker, click here.

The Moneymaker Effect proved a pleasant surprise, and not since Jim McManus’ Positively Fifth Street has a book more accurately and enchantingly captured a moment in WSOP history. It sounds cliché to say something is an instant classic, but that’s exactly how I felt after reading this book.

The art of the oral history is in the weave, and Raskin proved to be an expert weaver of a poker narrative. I actually had the chance to sit down with Raskin to ask him some questions about his book:

PokerNews: When and how did the idea to do this project come about?

Raskin: Before it was a book, it was a Grantland article, so I have to start there. My introduction to Grantland came when I was asked in 2011, shortly before the site’s launch, to write an oral history of the Sugar Ray Leonard-Marvin Hagler boxing match. At the time, I didn’t even know what an oral history was. But I took the assignment, really got into it, and started thinking about potential future oral history articles that I could pitch to them.

Since my areas of expertise are poker and boxing, the 2003 WSOP Main Event sprung to mind almost immediately. However, this was back in 2011 and my sense was that it would be best to wait for the 10th anniversary, so I sat on the idea for a while. In August 2012, I finally sent the pitch to my editor at Grantland, he ran it up the flagpole, and it got an immediate thumbs-up from Bill Simmons and Dan Fierman.

So that’s where the project originated. In terms of the idea to expand it into a book, I have to give some of the credit there to Phil Hellmuth. As we all know, Phil tends to think big, and as I was interviewing him he said straight up that this shouldn’t be a mere article, it should really be a book. So, that was my light bulb moment — and it was essentially Phil flipping the switch.

From there, I told my editors at Grantland that I thought I had enough material for a book, they told me they would do their best to help me secure the rights to my research since ESPN technically owned those rights the minute they commissioned me to write the article, I finished the article, and then I had to wait out a protracted legal slog while they decided whether to publish the book themselves or let me take it to another publisher. After I found an enthusiastic publisher — Huntington Press — Grantland eventually released the rights back to me, though the book came out a year after I’d initially envisioned it coming out.

An oral history seems easy to do in concept, but of course things like that are easier said than done. Just how difficult was the execution?

An oral history is ultimately an exercise in interviewing and editing, rather than writing. I find the final stages of the process to be tremendously enjoyable; once I have all my quotes transcribed, I’m essentially putting together pieces of a puzzle, making them fit in the right way to tell the story.

The hard work is the interviewing process; tracking people down, asking them the right questions, drawing interesting answers out of them, getting them to provide exposition at times, and then transcribing everything. That’s the part of the process that is exhausting and time consuming. Conducting and transcribing the interviews for this oral history was essentially a full-time job for me for six weeks in August/September of 2012.

You interviewed dozens of people for this book. Who was the most difficult to get?

Among those who were ultimately interviewed, the answer has to be Phil Ivey. He was so difficult to get that I didn’t get him the first time around. In the Grantland version, there are no quotes from Ivey. I asked Barry Greenstein if he could help me; no dice. I asked Daniel Negreanu if he could help, and he responded, “I think you’re drawing pretty dead on that one.”

But in the summer of 2013, my colleagues at ALL IN were setting up for a sit-down video interview with Ivey and consulted with me about questions to ask, and I made sure to sneak in a few about the ’03 WSOP and his clashes with Moneymaker. Ivey is the one and only interview in the book that I didn’t conduct myself. Ryan Johnson and Pete Findley from ALL IN conducted that interview and used some of Ivey’s quotes in the videos we posted, and I transcribed the interview for both ALL IN’s purposes and the purposes of my book.

Among those people I interviewed during the initial go-round in 2012, the toughest to line up was Sammy Farha. I had to wait about a month for that one to come off. Sammy just keeps a wildly unpredictable schedule, and we aren’t often awake at the same time (I’m an east coaster with a nine-to-five and young kids), but eventually, I got him on the phone — and thank goodness, because after Moneymaker, he was the next most essential interview. There would have been a gaping hole in the article and the book without Sammy’s perspective.

How were you able to get Howard Lederer? Were there any conditions to getting him to talk with you? Likewise for Annie Duke?

I preemptively established my own set of conditions for getting Howard to talk to me. I knew that he hadn’t spoken with any media at all since Black Friday (this was a couple of months before PokerNews’ “The Lederer Files” series), so I wasn’t sure if he would make himself available or not, but I had his personal email address and dropped him a line, specifically spelling out that I was writing an oral history of the 2003 Main Event and that I would not ask him any questions about Full Tilt Poker. And he emailed right back and said he’d be happy to do it.

So, to the best of my knowledge, this was the first interview Howard gave after Black Friday. And, whether readers hate Howard or not, the reality is that he went deep in the tournament that year, he’s a part of the story, and frankly, the book wouldn’t have been nearly as good without him.

Howard gave me Annie’s phone number and helped facilitate that interview. I actually felt somewhat bad, as almost all of my interview with Annie ended up on the cutting-room floor in the Grantland piece — the only quote that survived my personal edits and then my editor’s edits was one where she called herself an idiot for not foreseeing the viability of poker on TV. Fortunately, I was able to work many more of her quotes into the book and do her some justice. Again, love her or hate her, I feel strongly that Annie’s memories from Binion’s and the early days of the boom add color to the overall story.

Is there anyone you wanted to interview that you didn’t get the chance to?

Yes, several people. There was nobody who I considered “essential,” but there were a few people I would have liked to have interviewed — especially if I’d known all along that I’d be writing a book with an unlimited word count. Probably the most significant absence is Johnny Chan. I tried to reach out to Johnny and never heard back, but I didn’t push too hard because, well, I’ve interviewed Johnny before and his quotes usually aren’t all that illuminating.

I wanted to interview Moneymaker’s ex-wife, but Chris told me he has nothing to do with her anymore, and without his help I had no way of tracking her down. Same thing for Bruce Peery, Chris’s friend who convinced him to play for the WSOP seat. Peery was a fairly important part of the Moneymaker story, but Chris isn’t in touch with him anymore and I wasn’t able to track him down through social media the way I was some other people.

I took a stab at trying to get Becky or Nick Behnen to give the Binion’s perspective, but got nowhere; thankfully, Nolan Dalla did a great job telling that end of the story.

I left a message or two for the previous year’s champion, Robert Varkonyi, and never heard back. I similarly struck out in my pursuit of contact info for Paul Darden, Jason Lester, Sam Grizzle, and David Grey. And then there was Jim Miller, who was the co-tournament director alongside Matt Savage, and who actually played in the Main Event and cashed! He would have been a great side story, but nobody could track him down for me.

In the end, had I known all along I was writing a book, I might have tried harder to pursue a few of these interviews, but thinking that I was writing an article for Grantland that was going to be capped at about 14,000 words, it simply wasn’t worth it when I already had some 80,000 words worth of strong material and was agonizing over every cut.

Which interview subject was the most helpful to you on this project?

There are three I’d single out as extremely helpful in different ways. First is Moneymaker, who gave me the longest interview (more than two hours, spread over a few sessions) and never once made me feel like I was being a burden to him.

Second is Nolan Dalla, who provided so much essential background information that nobody else could and who helped put me in touch with a few of the interview subjects I was struggling to track down. And third is Brian Koppelman, who was kind enough to write the foreword to the book in addition to sitting for an interview.

One angle many people might not think of is the TV angle of the 2003 WSOP story. What inspired you to delve into that area?

I knew from day one that I wanted to explore that, because the hole-card camera and ESPN’s presentation of the tournament were as important to the way poker took off as Moneymaker winning was. I didn’t necessarily go in knowing what particular people I wanted to talk to; other than Norman [Chad] and Lon [McEachern], all I knew was I wanted to talk to someone from the production team and someone from the executive side at ESPN.

I found the story of how ESPN went from a one-hour final table broadcast without hole-card cams to this revolutionary seven-episode poker production every bit as fascinating as Moneymaker’s story. Very little of that made the Grantland version, and my desire to get those stories out there was a huge factor in motivating me to publish the book.

Any chance we see you do an oral history on other WSOP final tables?

Never say never, right? But if I had to guess, I’d say you won’t ever see that, just because there isn’t another WSOP Main Event that crosses over beyond the hardcore poker fan the way ’03 does. I forget who it was, but one of my interview subjects told me I should do 2004 next, that there are a lot of stories worth telling from that WSOP. And I don’t doubt that there are. But ’03 was the Main Event that changed everything. By ’04, the change had already more or less taken place, and that isn’t nearly as interesting to me.

Pick up your copy of the Moneymaker Effect in the PokerNews Book Section.

*Lead photo courtesy of cardplayerlifestyle.com.

Get all the latest PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!