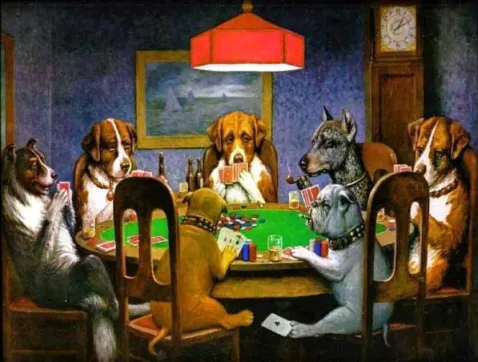

Poker & Pop Culture: Dogs Playing Poker

We all know them. Those bulldogs, mastiffs, St. Bernards, collies, and other breeds all absurdly gathered around a table, smoking pipes and cigars, drinking whiskey and beer, and, of course, playing poker. Perhaps some of us have prints hanging on walls in the near vicinity of where the home game is played, humorously reflecting the machinations of those sitting below, battling for chips like they were so many dog biscuits.

The series of paintings commonly referred to as "Dogs Playing Poker," the first of which was painted over a century ago, have long-enjoyed iconic status in American popular culture. For some the paintings represent the epitome of kitsch or lowbrow culture, a poor-taste parody of "genuine" art. For others they stand as cogent, insightful symbols of America's middle class. Many, though, for various reasons, have a genuine fondness for the humorous paintings, which arguably stand among the most well-known depictions of poker in mainstream popular culture.

Paintings for Cash

Born in 1844 in upstate New York, Cassius Marcellus Coolidge was nearly 60 years old when he began the series of paintings, having already lived through many other careers by the time he would create the works for which he is best known. Among other pursuits, Coolidge had been a school superintendent, a town clerk, a small business owner, and had worked in the banking industry, having opened and help run the first bank in Antwerp, NY. Coolidge had also gathered some journalistic experience during which his earliest artistic works appeared in the form of illustrations for a column he wrote. He even penned a comic opera about a mosquito infestation in New Jersey titled King Gallinipper, which was performed in the 1880s.

Nicknamed "Cash," Coolidge was something of an entrepreneur, having come up with a handful of money-making ideas and innovations along the way, too. The best-known of these is probably the one he called "comic foregrounds," those life-sized portraits with the heads cut out one often finds at amusement parks and in similar venues. So the man who painted the poker-playing dogs is also responsible for all of those pictures of us as a "Fat Man in a Bathing Suit" or "Man Riding a Donkey."

In 1903, Brown & Bigelow, an advertising firm located in St. Paul, Minnesota, hired Coolidge to paint a series of oil paintings for calendars advertising cigars. Thus did the paintings originate as part of a commercial venture, not necessarily borne from any purely "artistic" or non-mercenary inspiration. Though only a fledgling company at the time, Brown & Bigelow would go on to publish many of America's most popular calendars in the 20th century, ranging from Norman Rockwell's famous Boy Scout calendars to those featuring Gil Elvgren's "pin-up" girls.

As it happened, Coolidge had been painting dogs since the 1870s, including some that had appeared on cigar boxes. Some of his paintings of dogs featured them in human poses, which was precisely what the firm wanted for their calendars. Coolidge would eventually produce 16 different paintings for Brown & Bigelow. The calendars were an immediate hit, and Coolidge was also able to sell the original paintings for prices ranging from $2,000 to $10,000. Such prices further testify to the paintings' popularity, as for the time period those were not insignificant sums to be fetching. (Pun intended.)

Bluffs, Booze, and Barks

Not all of the 16 paintings Coolidge completed for the calendars featured dogs playing poker. Seven depict canines mimicking a variety of other human activities, such as attending a baseball game, conducting a trial, playing pool, struggling over a broken down Model T, or celebrating New Year's Eve. The other nine all do involve poker in some fashion, however, and taken together the series neatly conveys various scenarios and settings commonly associated with our favorite card game.

None of the paintings are actually called "Dogs Playing Poker," although that's the title often mistakenly given to the most popular of the series, "A Friend in Need." That's the one featuring seven dogs gathered around a table smoking, drinking, and intently studying their cards (and each other), the scene starkly-lit by the red lamp hanging overhead. We see the game isn't on the up-and-up, as the cigar-chomping gray bulldog in the foreground is holding the ace of clubs in his extended paw under the table, apparently passing it to the tan-haired bulldog on his left who looks to be holding the other three aces. As the smallest dogs at the game, perhaps these two struck up an alliance for dealing with their larger opponents.

Two of the paintings, "A Bold Bluff" and "Waterloo," tell a sequential story in a manner resembling the works of the great 18th-century painter William Hogarth. In the first, a St. Bernard appears in the foreground on the left, a large tower of chips which he has presumably just pushed forward sitting in the center of the table before him. The other dogs look at him intently, but he gives away nothing behind the pair of spectacles resting on his snout. In the second painting, his hand — a modest pair of deuces — has been revealed to the others. The St. Bernard grins as his paws rest on the large pile of chips he has just claimed, the other dogs registering various forms of surprise and dismay, having fallen victim to the bold bluff.

For some of the paintings, Coolidge moves the dogs' games to other locations. "His Station and Four Aces" shows a card game on a train, with the dogs wearing an assortment of hats and coats suitable for travel. A conductor has interrupted the game to inform an aghast-looking player the train as reached his stop. Bad timing! He has four aces! Another painting, "Stranger in Camp," finds the dogs at a campsite, apparently in conflict as the chips and cards are all scattered about with two of the players locked in what looks to be a pre-fight staredown.

"Pinched with Four Aces" takes us back to the home game, this time being broken up by four dogs in police uniforms. "Poker Sympathy" shows a poor boxer falling back in his chair, his beer spilled and his four aces sliding off the table in response to seeing his opponent's straight flush. "Post Mortem" shows the cards stacked on table with just three dogs seated around it, still drinking, smoking cigars, and ostensibly discussing the night's activities.

Finally, "Sitting Up with a Sick Friend" is the only one of the nine to feature female dogs, so designated by their fashionable hats. Given the scene, the title appears to describe the lie told by the men to the women regarding the true nature of their gathering. One of the female dogs has an umbrella raised as if to strike one of the players, as a guilt-confirming playing card falls from the table in the foreground.

It's a Dog Eat Dog World

As that latter painting underscores, the scenes presented in Coolidge's "Dogs Playing Poker" paintings — as well as in his other paintings for Brown & Bigelow's cigar-selling calendars — is a decidedly male-dominated one. And given the focus on typically masculine activities like playing poker, fixing cars, and, necessarily, smoking cigars, it somehow seems appropriate that Coolidge chose dogs to anthropomorphize in his paintings.

In a 2002 New York Times article, Coolidge's daughter, Gertrude Marcella Coolidge, then 92, tells how she and her mother preferred cats to dogs, and wonders what the paintings would have been like had her father gone in a different direction. "You can't imagine a cat playing poker," she ultimately concludes. "It doesn't seem to do."

Was it Coolidge's purpose, then, to satirize male behavior as somehow animal-like? Or was his target much broader, incorporating the whole of the American middle class and its values? In their 2004 book Poplorica: A Popular History of the Fads, Mavericks, Inventions, and Lore that Shaped Modern America, Martin J. Smith and Patrick J. Kiger speculate that Coolidge indeed intended the series as a satire. They point out how "A Friend in Need" uncannily echoes Georges La Tour's 17th-century painting The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds, a painting clearly intended to "expose the moral turpitude of the upper classes."

Does such an allusion indicate Coolidge was using a commercial medium to make a similar pronouncement about middle-class America? If he was, middle-class America doesn't seem to have minded very much. Over the years the popular paintings have been widely reproduced in a variety of media, including as posters, figurines, needlepoint kits, clocks, coasters, and, most suitably, on the backs of playing cards, not to mention being frequently alluded to in countless other works of popular culture, including television shows, music, film, and even video games.

A certain member of the upper class likes the paintings, too. At an auction in 2005, a private collector from New York City purchased the originals of "A Bold Bluff" and "Waterloo" for a cool $590,400. The auction's director cited poker's booming popularity as a direct cause for the much-higher-than-anticipated price tag.

Over half a million! That's a lot of bones for just a pair.

Image: "A Friend in Need” by Cassius M. Coolidge, public domain.